if F. Scott Fitzgerald had owned a computer, Gatsby might be twice as long and half as great.

Improbable as it now sounds, students in my early classes generally wrote their papers by hand. You could tell something about the student just from the look of the paper, before you had read a single word. Could you ever! Dartmouth was then all male. Once I traded a set of freshman themes with a friend who taught at a women's college. My boys (as we called them then) were to grade her girls, and vice versa. Just the sight of that feminine handwriting produced a near-riot when I passed the papers out. There were boys—men of 18—half in love, just from the way some woman of 18 made her capital letters.

Obviously that couldn't happen now. Every student at the College is required to have a computer, and about half also have printers. Even if some maverick decided not to use his or hers, I probably wouldn't accept a handwritten paper. Reading exams is bad enough.

But for a slight loss in individuality, has there been a big gain in quality? Yes, sometimes there has. Certainly students are far more willing to revise a paper now that it does not mean retyping or recopying it. And because, except for a handful of born writers, the second version is apt to be better than the first, and the third than the second, the general level of student writing has risen. Current students are no smarter that I can see, and certainly they are not better read. (Almost the only book you can count on every student having read is The Great Gatsby, which has the double virtue of being very romantic and very short.) They just have computers and printers.

But—and from a curmudgeon you knew there was a but coming—along with the expensive equipment comes a problem. It's the same problem Henry james faced a hundred years ago. Up until 1896 James wrote his novels and stories out by hand. Then arthritis made this increasingly painful, and he began to dictate them to a typist. She typed as he talked. He would read her draft, and then dictate revisions. It was all much easier.

Guess what. It made him verbose. The famous Jamesian "late style" is partly a result of seeing life ever more complexly, but it's partly also a result of composition being so easy. Atypical result: Back in handwriting days, James produced an essay on a famous French actor. It's 5,800 words long, and it came out in The Century Magazine. Years later an editor wanted to reprint the piece in a book. James agreed. He did no updating, added no new material, not one new fact or idea. But he did reread the essay—and then he dictated a 7,200- word revision to his secretary.

Computers and printers are not exactly like secretaries (though they will be, once the voice-operated models are perfected. English professor Ernest Hebert's is pretty far along right now). But they are close enough so that the danger of verbosity comes with them. That's why I often tell students, when I ask them to rewrite a paper, that far from wanting it longer, I'd like to see them shorten it a bit. It's why I'm just as glad F. Scott Fitzgerald didn't own a computer. Would you prefer Gatsby in two volumes? And, alas, it's why the quantity of stuff I get from various College offices is somewhere between five and ten times greater than it was when I came here.

I understand alums have the same problem.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

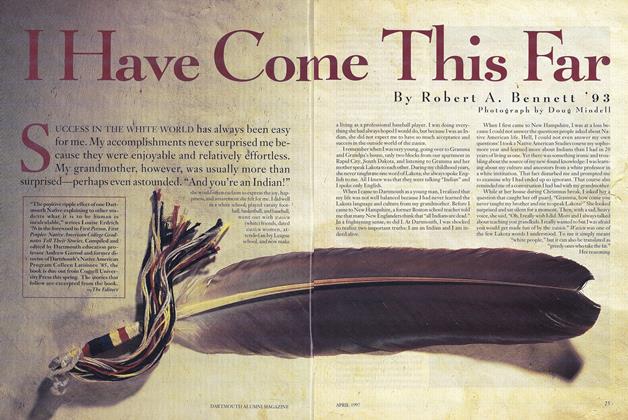

Cover StoryI Have Come This Far

April 1997 By Robert A. Bennett '93 -

Feature

FeatureNative America at Dartmouth

April 1997 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

April 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

April 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

April 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe Are Not Your Indians

April 1997 By Arvo Mikkanen '83

Noel Perrin

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Books

BooksTHE DISPLACED PERSON'S ALMANAC.

March 1962 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleOf Politeness and Pedestrians

OCTOBER 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleUntenured Gems

JANUARY 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

OCTOBER 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleYou Are Here

MAY 2000 By Noel Perrin