By the time first-year students read the "Principle of Community," they already feel as if they belong to one. On a Dartmouth Outing Club trip they have hiked, camped, and danced with equally bright individuals who have the same thing on their minds: We are part of Dartmouth now. The hugs exchanged at the end of the trip are more than embraces; they are acknowledgments of membership.

For me that all-inclusive feeling didn't last. In the fall of my junior year, I produced a radio show for WDCR entitled "Dartmouth Dialectic" that featured representatives from the conservative Dartmouth Review, the feminist Spare Rib, the conservative Beacon, and the liberal Bug debating topics of national and campus interest. Although I had anticipated spirited disagreement, I had not expected these journalists' open hostility. It would have been inconceivable for two opposing members of the panel to go to lunch together, much less voluntarily include themselves in a true community.

During my senior year, I attempted to find the truth about community at Dartmouth by conducting a study for an honors thesis under the supervision of Professor Jim Kuypers. Students in the study pointed to the tension between diversity and community. Said one participant, "I thought the point of the admissions process was to pick a hugely diverse group of people. We all got here because we're different and special in our own way, and that necessarily makes for not big community." Said another, "The idea of a community in the real world is Italian and Irish neighborhoods in Brooklyn. People divide themselves along ethnic or racial lines. That also ends up happening here." Students listed race, ideology, economic status, even affinity as social divisions among themselves.

Nonetheless, participants were unwilling to abandon their belief in community. They cited communal experiences on foreign study programs where students' only bond is their affiliation with Dartmouth as proof that differences can be overcome. So why do barriers persist in Hanover? One participant likened Dartmouth community to a Russian matryoshka doll. On campus, students create narrow boundaries for their communities, but as they move farther away from Dartmouth, those boundaries widen. In other words, students forsake their connection to each other until they are in situations where that tion is less common. I heard that this occurs most profoundly after graduation, explaining, in part, Dartmouth's zealous alumni network.

If community is not something a Dartmouth student appreciates until he becomes increasingly removed from it, how is Dartmouth ever a community in practice? An optimistic firstyear student, not far removed from the visceral experience of his DOC trip, proposed one answer. He said, "The ideal community for Dartmouth, in my mind, is very similar to the one we have. It's just a whole bunch of people, with a whole bunch of interests, who can sit around and talk about them and try to learn from each other." I remained unconvinced when I turned in my thesis and graduated.

Then I gained insight in an unexpected way: Dartmouth hired me as an admissions officer. On the first day I returned to Hanover, I was greeted by a fellow admissions officer and alumnus, a person I had never met while an undergraduate. Instead of giving me the handshake expected from a new coworker, she gave me a hug.

started this summer as an assistant admissions director at the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

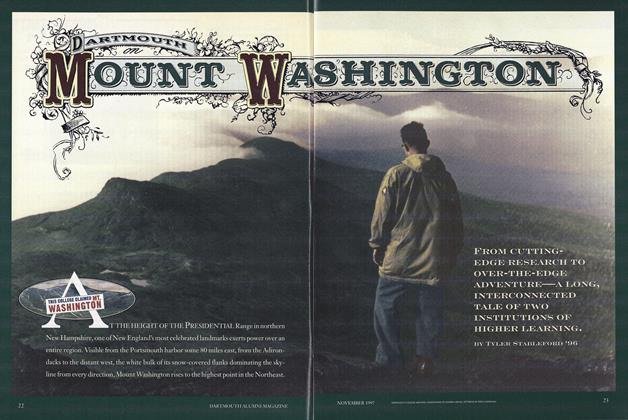

Cover StoryDartmouth on Mount Washington

November 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Feature

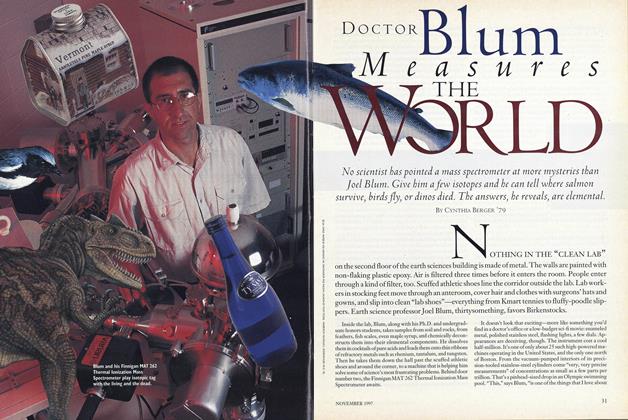

FeatureDoctor Blum Measures the World

November 1997 By Cynthia Berger '79 -

Feature

Feature"Hi. My Name's John. I'm a Zero."

November 1997 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Article

ArticleThe Truth, The Half Truth, and Nothing of the Truth

November 1997 -

Article

ArticleThe President Steps Down

November 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Collis Silverware Mystery

November 1997 By Noel Perrin