ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ART

For the past eight years Hanover has been acquiring a new look in residential architecture. Primarily responsible are Ted Hunter '38 and his wife Peg, both graduates of the Harvard School of Design and partners in the architectural firm of E. H. and M. K. Hunter, established in Hanover in 1945.

The Hunters have been particularly successful in adapting contemporary design to North Country conditions and living. Ted Hunter's article answers the question "Why modern design?" but more specifically "Why modern design for this region?"

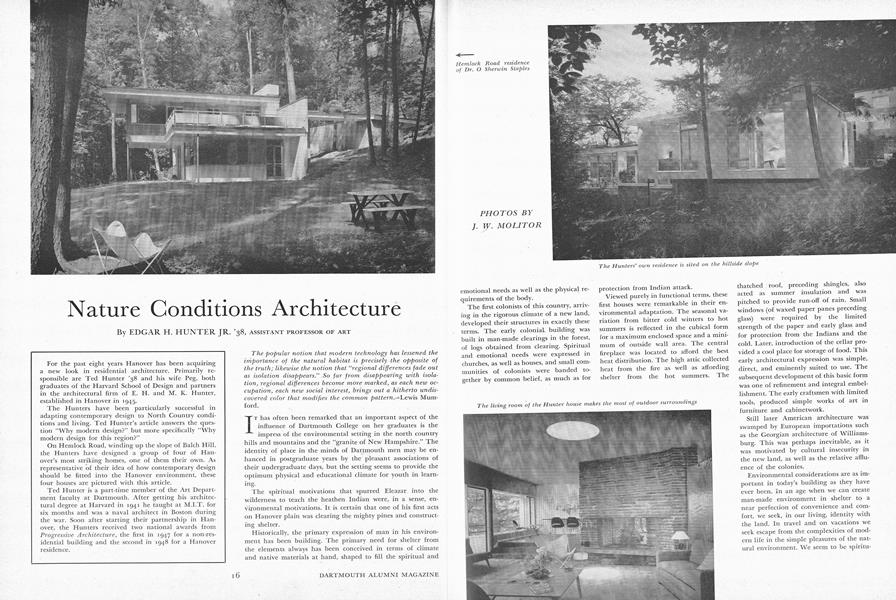

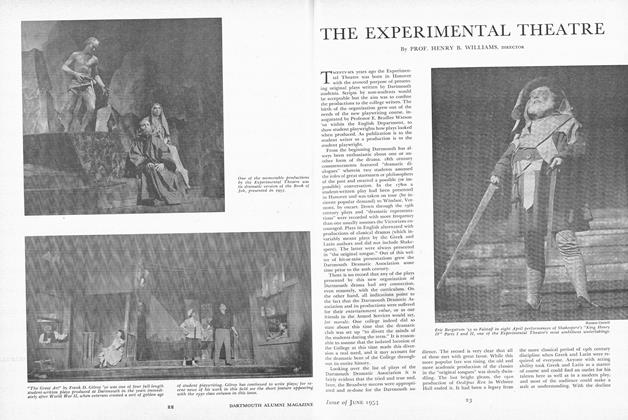

On Hemlock Road, winding up the slope of Balch Hill, the Hunters have designed a group of four of Hanover's most striking homes, one of them their own. As representative "of their idea of how contemporary design should be fitted into the Hanover environment, these four houses are pictured with this article.

Ted Hunter is a part-time member of the Art Department faculty at Dartmouth. After getting his architetural degree at Harvard in 1941 he taught at M.I.T. for six months and was a naval architect in Boston during the war. Soon after starting their partnership in Hanover, the Hunters received two national awards from Progressive Architecture, the first in 1947 for a non-residential building and the second in 1948 for a Hanover residence.

The popular notion that modern technology has lessened theimportance of the natural habitat is precisely the opposite ofthe truth; likewise the notion that "regional differences fade outas isolation disappears." So far from disappearing with isolation, regional differences become more marked, as each new occupation, each new social interest, brings out a hitherto undiscovered color that modifies the common pattern.—Lewis Mumford.

IT has often been remarked that an important aspect of the influence of Dartmouth College on her graduates is the impress of the environmental setting in the north country hills and mountains and the "granite of New Hampshire." The identity of place in the minds of Dartmouth men may be enhanced in postgraduate years by the pleasant associations of their undergraduate days, but the setting seems to provide the optimum physical and educational climate for youth in learning.

The spiritual motivations that spurred Eleazar into the wilderness to teach the heathen Indian were, in a sense, environmental motivations. It is certain that one of his first acts on Hanover plain was clearing the mighty pines and constructing shelter.

Historically, the primary expression of man in his environment has been building. The primary need for shelter from the elements always has been conceived in terms of climate and native materials at hand, shaped to fill the spiritual and emotional needs as well as the physical re quirements of the body.

The first colonists of this country, arriving in the rigorous climate of a new land, developed their structures in exactly these terms. The early colonial building was built in man-made clearings in the forest, of logs obtained from clearing. Spiritual and emotional needs were expressed in churches, as well as houses, and small communities of colonists were banded together by common belief, as much as for protection from Indian attack.

Viewed purely in functional terms, these first houses were remarkable in their environmental adaptation. The seasonal variation from bitter cold winters to hot summers is reflected in the cubical form for a maximum enclosed space and a minimum of outside wall area. The central fireplace was located to afford the best heat distribution. The high attic collected heat from the fire as well as affording shelter from the hot summers. The thatched roof, preceding shingles, also acted as summer insulation and was pitched to provide run-off of rain. Small windows (of waxed paper panes preceding glass) were required by the limited strength of the paper and early glass and for protection from the Indians and the cold. Later, introduction of the cellar provided a cool place for storage of food. This early architectural expression was simple, direct, and eminently suited to use. The subsequent development of this basic form was one of refinement and integral embellishment. The early craftsmen with limited tools, produced simple works of art in furniture and cabinetwork.

Still later American architecture was swamped by European importations such as the Georgian architecture of Williamsburg. This was perhaps inevitable, as it was motivated by cultural insecurity in the new land, as well as the relative affluence of the colonies.

Environmental considerations are as important in today's building as they have ever been. In an age when we can create man-made environment in shelter to a near perfection of convenience and comfort, we seek, in our living, identity with the land. In travel and on vacations we seek escape from the complexities of modern life in the simple pleasures of the natural environment. We seem to be spiritually reassured in the presence of Nature: the majesty of the mountains, the tempestuous moods of the sea, of the serenity and solitude of the deep woods.

The question of participation of nature in the man-made environment is one of degree. Urban and suburban areas are characterized by extensive land alteration to fit human needs. In the city, where the physical environment has been shaped by man to the point of apparent subjugation of nature, climate and seasonal change still play a vital role. The suburban area, although highly developed and shaped to man's needs, is permitted more natural landscape forms by a lower density of the population. The inclusion of nature in these areas and the aesthetic satisfaction derived from the contrast of natural forms of landscape to man-made forms of buildings may be the single most important criterion of whether the city or suburb is a pleasant place to work and live.

The rural area may be largely agricultural in aspect. In such a productive area man meets on friendly terms with organic nature, cooperating in a partnership in which neither dominates. This is a cooperative effort in which a satisfying aesthetic usually results.

The primeval area may be desert or forest, mountain or plain. Here is land too rough, dry, or sterile for agriculture, or too remote for concentrated development. These areas are of vital importance to us, because of water resources, extraction of timber or mineral wealth, or the grazing of cattle or sheep, in addition to the recreational potentials of natural scenic beauty. Conservation of such primeval areas implies sensible development for today's uses and those of future generations, rather than allowing their potentials to remain untouched and dormant.

Concepts of regional planning are based on sound conservation principles, and seek the integrated development of large land areas, in terms of the benefit and enjoyment derived by humans from natural resources.

THE smallest yet most vital organism of planning for man's enjoyment is the residence. Herein lies the greatest opportunity for expression of the individual and his relation to others and his environment.

The contemporary architect, working in the residential field, has the exciting challenge of creating a vital architectural expression; of interpreting the individual in his relationship to region and human society, for it is under this understanding that he designs. This is a totally different concept than the commonly held viewpoint that the architect's job is to put a socially acceptable face on structure.

As the cost of building has increased per cubic foot of enclosed space, and a larger proportion of the building dollar has gone into mechanical aids, the actual size of the enclosed space in a home has decreased. Here the contemporary architect has played an important role in achieving greater visual space by designing interior spaces that flow into each other where appropriate to use and by planning areas in terms of specific and convenient function. This spacious feeling is further increased by projecting the plan outward to include exterior space and reducing visual boundaries defining the interior by use of glass and other architectural means. Such visual space flow can mean a greater affinity of the house with its setting. It can promote a restful and peaceful atmosphere within the home as well as provide the stimulation of the slow dynamic of seasonal cycle and weather change. This living with the outdoors can be drastically changed at will by curtain closures to permit the room to turn in on itself and focus inward to the family group around the fire.

The question of privacy within the interior is a valid one with the visual inclusion of exterior space. The possibility of opening the house to the outside brings with it the necessity of careful evaluation of the view to be included from within, as well as the protection of privacy from without. There is no question of the serious abuses in use of the so-called "picture window." In many houses being built today the inclusion of this architectural cliche is very ill-considered. In suburban areas such treatment should involve creating a near view, such as a garden or terrace, with privacy obtained by planned enclosure by hedge or fence.

In addition to the needs of privacy, there is the importance of careful orientation to the sun, in the disposition of large glass areas, so that the benefits of winter sun can be obtained, while excluding the excessive heat of the summer sun. This may be accomplished by provision of roof overhang for the shading of the southern glass. Solar angles in altitude vary by latitude and between winter and summer solstice. Calculation of these angles in relation to compass orientation and height of the window allows the desirable extent of roof overhang to be accurately figured.

This instance of the utilization of natural forces for human benefit through design is an important aspect of conservation principles applied to the residence. Through such exploitation of climate we can condition natural forces to best serve our shelter from the elements.

Though more than anything else today we need security, peace and relaxation in our homes, we also derive benefit from aesthetic stimulations of color, form, and texture, of contrasts in openness to enclosure, or the play of light and shade.

Advances in building techniques and introduction of appropriate new materials can do much to make homes more durable and cheaper to build, as well as more satisfactory. The use of manufactured parts does not necessarily imply architectural conformity or subjugation of the individual to a common standard. It is a popular inaccuracy to compare house production with automobile production that takes advantage of repetitive operations. The automobile, viewed in its simplest terms, is a mechanical contrivance for transportation, and its temporary nature is recognized by the yearly trade-in. The house, on the other hand, fills more enduring requirements and is far-reachingly important as the physical locus of all family life. By use of standardized elements of construction, however, the possibilities of individual variation are virtually without limit. It is in this direction that prefabrication should develop.

Houses are usually thought of simply as a commodity without other significance. The average person may be so used to living in poorly planned space and environment, that given an opportunity to start afresh, he will demand identical surroundings.

Satisfactory planning for specific circumstance and in relation to environment precludes the casual operations of the inexpert land subdivider and developer.

It is a mistake to view any given example of planning or architecture out of its environmental context, for in another region, the solution would be predicated on different circumstances.

This is the age of science, and the role of artist and architect alike, as necessary and vital members of society, is little understood. Great work in art and architecture, in the popular view, is something that was accomplished many years ago, its precepts leaving little to be desired, and standing ready to be drawn upon from museum sources, as needed.

This viewpoint overlooks the fact that truly great art and architecture always have sought to add richness to life by interpretation of their own times; to satisfy the emotional needs of their own day. This viewpoint does not deny the eternal value of the great art and architecture of the past; rather it recognizes these great traditions as of the greatest value when they are behind us, pushing forward.

We acknowledge the value of the scientist as necessary to our very survival, yet we are not aware of the potential value of the creative designer, artist, or architect, who must control all visual manisfestations of productive life.

These then are the real motivations behind contemporary, domestic architecture: to relate structure in a vital manner to the individual and his environment and to create an architecture that satisfies the emotional needs of today, taking advantage of both the experience of the past and the technological possibilities of the present.

Hemlock Road residenceof Dr. O Sherwin Staples

The Hunters' own residence is sited on the hillside slope

The living room of the Hunter house makes the most of outdoor surroundings

Bouchard Ted and Peg Hunter, Hanover's noted architectural team

Residence designed for the author's brother, Dr. Ralph W. Hunter '31

Newest of the Hemlock Road houses, owned, by Dr. Walter C. Lobitz Jr.

The Lobitz kitchen and its magnificent view of Vermont hills to the west

Bedroom of the Staples home, the only twostory house in the Hemlock Road group

Garden and steps to the bedroom wing of thehouse the Hunters designed for themselves

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

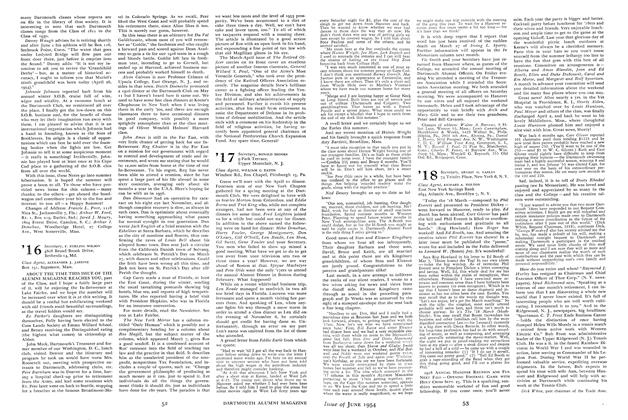

FeatureTHE EXPERIMENTAL THEATRE

June 1954 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

June 1954 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, ANDREW J. O'CONNOR, Richard Eberhart '26 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1954 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

June 1954 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

June 1954 By G. DOUGLAS MORRIS, WILLIAM B. MINEHAN

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArtistry on Film ... ... With Serious Intent

OCTOBER 1963 -

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

JUNE 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureJOHN THORNTON OF CLAPHAM

OCTOBER 1968 By FRANK W. FETTER -

Feature

FeatureThe Teacher of Social Science and the World Crisis

February 1954 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Feature

FeatureIt’s the Ideas, Stupid

April 2000 By KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81 -

Feature

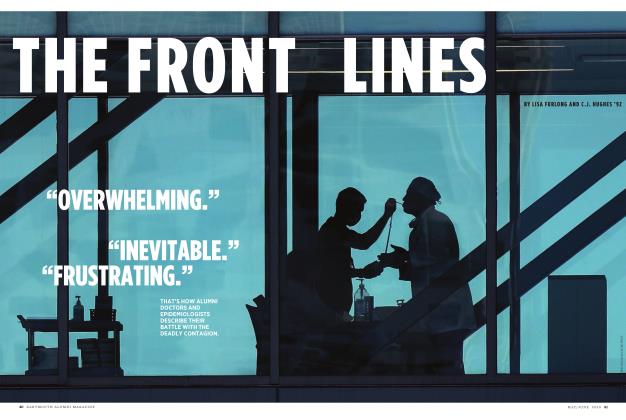

FeatureThe Front Lines

MAY | JUNE 2020 By LISA FURLONG, C.J. Hughes ’92