If the College recognized its distinguished alumni, the exchange of lustre would he equal.

Dartmouth has given more than a thousand honorary degrees over the years—and that's not even counting the honorary degree each faculty member gets when he or she is promoted to full professor. (Don't be envious It's only an M.A.)

There has been lots of variety. There have been His and Hers honorary degrees for the Earl and Countess of Dartmouth in 1969, for example. For John and Jean Kemeny. One year there were 28 recipients; they formed a group about the size of my daughter's high school graduation class. A couple of years there have been none at all. Some recipients almost make it a habit. Ezra Stiles, for example, got an honorary degree in 1779, and the very next year he came back to Hanover and got another one.

There is also the matter of who is honoring whom. Some recipients, like Alexander Hamilton in 1790 and President Madison in 1817,

shed lustre on Dartmouth. Some, like several hundred New England clergymen, got a little glory from the College.

The recipient who would have shed the most lustre, who would indeed have bathed the campus in retrospective glory, never got his degree. That happened, or rather didn't happen, in 1863. Seven Trustees met in Hanover with President Nathan Lord to pick candidates. At that time the College was averaging about 15 honorary degrees a year.

One Trustee proposed something radically different. Let us give a degree to Abraham Lincoln, he said, and to no one else. The Battle of Gettysburg had just been fought; the Gettysburg Address was yet to come.

Three other Trustees liked the idea; and the motion passed, four to three. President Lord then said he had the right to vote (some Trustees thought he didn't, except in the case of a tie), and he now voted against. Stalemate. End of plan. The College wound up giving six honorary degrees that year. None was of any special interest.

In recent years the College's policy has settled into a predictable and perhaps slightly boring pattern. There will be seven recipients, of whom two will be alumni. Or maybe there'll be eight recipients. Maybe just one alum. The rest will be prominent, worthy, and unconnected—the modern equivalent of all those ministers.

Dartmouth has a lot of distinguished graduates. I'd love to see one year where every single honorary degree went to alums, and where they were picked by field. There are some remarkably fine architects among our graduates. Include one of the best of them. There are brilliant bankers. One of them. Dartmouth grads have played amazing roles in the field of modern dance. One of them. Now a grad with a high elective office, who has served it well: a governor or a member of Congress. One of our best sculptors; there are several distinguished ones to choose from. A top lawyer, one of those honorable men and women who keep the rest of us from hating the whole profession. A teacher. (Not an educationist, a teacher.) One of the most farsighted of our industrial tycoons, of the kind who really will leave the planet a better place. Make it a fall dozen, every one a graduate.

I'm not suggesting this as a permanent change, but as a once-only, as in 1863. For me, one of this plan's many charms is that the exchange of lustre would be equal. Dartmouth would be honoring her sons and daughters, as they have honored her by becoming what they have become.

If just one more Trustee had liked the Lincoln idea in 1863, it would now be a legendary Commencement. It would be like that most famous of all issues of The NewYorker, the one where Harold Ross threw out everything else, even die movie reviews, and devoted the entire issue to John Hersey's long and powerful essay on Hiroshima.

I'm not making any such grand claim as that for an all-Dartmouth Commencement. But I think you have to grant this much. It would be kind of interesting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

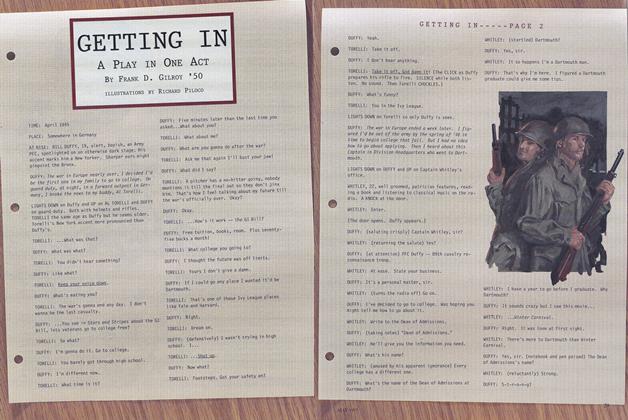

Cover StoryGETTING IN

May 1997 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

May 1997 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureDon't Call Me A Pundit

May 1997 By DIANE CYR -

Article

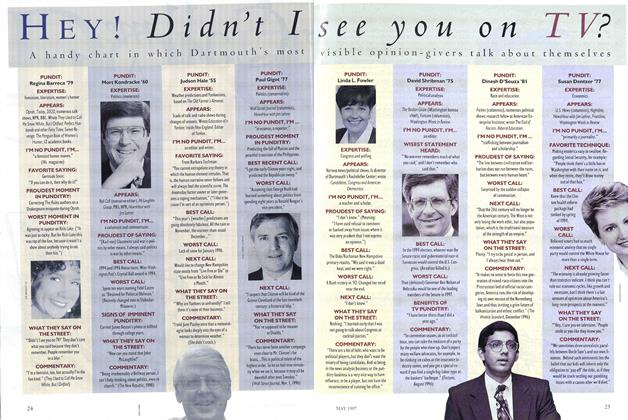

ArticleHey! Didn't I See You on TV?

May 1997 -

Article

ArticleCold Calculations

May 1997 By Christopher Kenneally 81 -

Article

ArticleBuildings Spring Up and Athletes Get Down

May 1997 By "E. Wheelock"

Noel Perrin

-

Books

BooksTHE LOST ART.

DECEMBER 1963 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

FeatureLast Person Rural

June 1992 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleOh, Professor, No Charge for You

APRIL 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleDartmouth, Dartmouth, Doing Right

OCTOBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty's Turn to Give

NOVEMBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Difference With Oberlin

APRIL 1998 By Noel Perrin