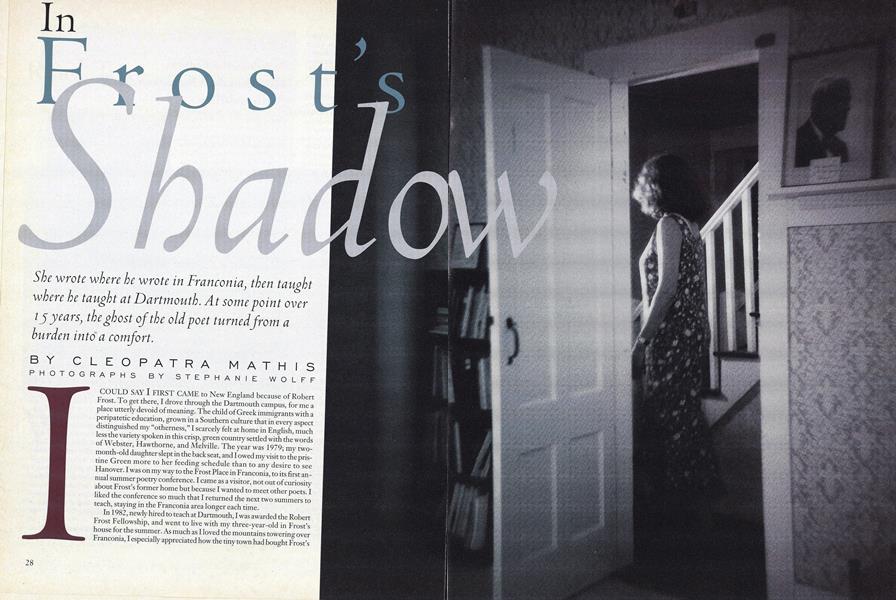

She wrote where he wrote in Franconia, then taught when he taught at Dartmouth. At some point over 15 years, the ghost of the old poet turned from a burden into a comfort.

COULO SAY I FIRST CAME to New England because of Robert Frost. To get there I drove through the Dartmouth campus, for me a place utterly devoid of meaning. The child of Greek immigrants with a peripatetic education, grown m a Southern culture that in every aspect distinguished my "otherness," I scarcely felt at home in English, much less the variety spoken m this crisp, green country settled with the words of Webster Hawthorne, and Melville. The year was 1979; my two- month-old daughter slept in the back seat, and I owed my visit to the pristine Green more to her feeding schedule than to any desire to see Hanover. I was on my way to the Frost Place in Franconia, to its first annual summer poetry conference. I came as a visitor, not out of curiosity about Frost s former home but because I wanted to meet other poets I liked the conference so much that I returned the next two summers to teach, staying in the Franconia area longer each time

In 1982, newly hired to teachar Dartmouth, I was awarded the Robert Frost fellowship, and went to live with my three-year-old in Frost's House for the summer. As much as I loved the mountains towering over Franconia, I especially appreciated how the tiny town had bought Frost's simple farmhouse and supported each young poet chosen to live there. The sixth such poet-in-residence, I had been living on grants for the past year and a half. The gift of a house, which the townspeople maintained and watched over (even bringing me firewood one summer night that proved unusually cold), plus a thousand dollars to cover living expenses, was a godsend.

Though I'd taught at three Frost conferences and spent considerable time exploring the grounds, I spent most days there at the barn, where most of our events took place. I'd never

spent a night in the house, never wandered through Frost's life as if it were my own.

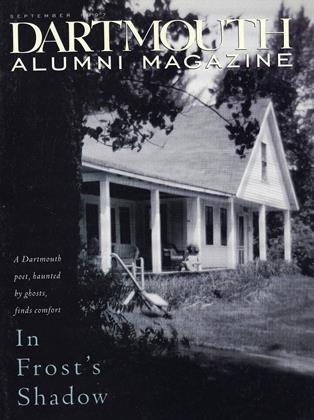

The 1870s white clapboard farmhouse is a reminder of the plain style for which New England is famous. From the long front porch, the house's only luxury, one can enter either through the living room door, part of the resident poet's private quarters, or, at the end of the porch, through the door leading to Frost's study. From the study, visitors enter the hall and take the stairs to the second floor, where one bedroom

serves as a second museum room for letters and period furniture. During the first weeks I lived in his house, I found myself trying to ignore the fact of Robert Frost's existence. I avoided his things whenever possible and retreated to the rooms that seemed less touched by his presence. I haven't been the only resident poet to panic in that austere silence of the Franconia woods. Katha Pollitt, the first Frost poet, once called David Schaffer (who co-founded the Frost Place along with Evangeline Machlin) during the middle of the night to come rescue her from the ghosts. And even if the noises turned out to be nothing more than the usual nocturnal creatures, the house does have a certain, I think not altogether benign, presence.

I rocked on the Frost porch most evenings long past sundown, a notebook in my lap, my eyes fixed on the lovely lines of the mountains rising in front of me, avoiding die framed poem, "New Hampshire," mounted on one of the porch posts. I sat there, reluctant to go inside the silent house, daydreaming not of Frost or the new job I'd be coming to but of all the past personal failures I felt constricted and defined by—my inability to sustain a marriage, my fear that I'd lost faith in the test of any true feeling. Fearful of love, I told myself that nothing mattered but commitment.

My little daughter lay sleeping a few feet away in a corner of the living room, where I'd made our beds. I was afraid of the bedrooms and avoided altogether the museum areas. Nevertheless, my daughter was deeply attracted to Frost's study, the front room containing the best of Frost memorabilia: his desk, some first editions of his books, a large framed picture of the handsome 40-ish Frost, and his Morris chair. Next to the desk stood a platform cherry rocker.

I found this room the most intimidating: too quiet, filled with itself. I never lingered there, only walking through when I absolutely had to. But this was where my daughter wanted to live, and every evening before bed she led me to his rocker. "Can we rock here?" she asked repeatedly. I wish I could say I understood her desire, that I let her take me there to rest in Frost's benevolent stare. I wish that she and I, homeless—having moved a couple of times a year since her birth—found a resting place. That whatever connection she nourished, made manifest in that room, was recognizable to me and I embraced it. But I didn't. Cowed by something I couldn't define, I felt lonely, furtive, without connection to the poet or to the great endeavor for art that he represented. I couldn't see his own unstable life, his domestic fears and failings. I only measured his achievement, his great, articulate, American nature.

It puzzled me that I avoided Frost's presence, even the haunting presence of his poems, which I loved. That act of independence somehow comforted me. I spent my days furiously at work on my second book, an elegy for my murdered brother, squirreled away in the topmost, farthest corner of the house, staring out a window that mercifully withheld a view of Frost's mountains or Frost's barn, but looked instead into a pathless section of deep, anonymous woods. A talented friend from my graduate school days at Columbia gave up poetry because she said she couldn't bear the ghosts of the great writers peering over her shoulder. Moored and defined by the greatNew England tradition of literary excellence, she couldn't put that standard aside. Deep in my rural, uneducated corner of Louisiana, I had the blessings of a certain ignorance. Until I came to Frost's house, I lived with great writers as though with the dimmest of shadows, easily escaping whatever doubt they could cast on my own work.

IN 1915 ROBERT FOST CAME BACK to New England after escaping to England for four years to find success as a poet. Celebrated there but not here, he returned to live on a little farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, to become, as he putit, "Yankier and Yankier." Intentionally, deliberately, he took on a persona, understanding that regardless of any birthright, he was temperamentally an outsider. I like to think of Frost coming back to settle on his little farm, at home on his porch in the long summer evenings, working, as he often did, through the night. I see him as a stranger there, not the comfortable farmer I once imagined.

I know now that the 18-year-old boy who came to Dartmouth in 1892 came feeling very much like an outsider. I know he lasted in Hanover only a few months, fleeing as he would other New England towns in his lifetime. He spent his first semester living in his poems, his refuge since high school, mostly ignoring the other students (and suffering the penalty of their teasing). Most days, after morning classes, he left the campus, walking north from what is now Greensboro Road to Etna Road and Hanover Center, under the shadow ofMoose Mountain, all the way to Goodfellow, where he'd turn and head back to town. "My Butterfly: an Elegy," one of his first accomplished poems, was written after one of those walks. Homesick as he was and longing for Elinor who'd graduated from high school with him and gone off to her own college life, the butterfly was emblematic of his first love, now feared lost, as well as a lost season:

I found that wing broken today! For thou art dead, I said, And the strange birds say. I found it with the withered leaves under the eaves.

I didn't know when I lived those months in the Frost house that I too would find my way to Etna Road, that the 200-yearold house I'd move into when I remarried would be the same house that Frost saw as he turned onto Goodfellow Road. Running that road for all these years, I imagine Frost seeing what I see in the weeds and fields and gardens. I've lived here long enough now to watch one great haytield on Good fellow give itself over to pine and shadbush. And every year Frost the life of the man, not just the poems he left has come closer. I tell myself we share a view: the same mountains, the same birds, but that's only coincidence. The real intimacy 'is something I've been able to recognize only as I've gotten older—the certainty that all of us struggle with alienation of some sort, both fearing it and fearing its defeat.

Is it because of this that I've learned to love every writersimply for the devotion and struggle and honesty that writing requires of us? When I first read Frost's butterfly poem, only a few years ago, I startled, remembering the dead monarch I'd found running on Ridge Road, Frost's road in Franconia. It was the day before Labor Day, when I was scheduled to leave for Hanover and my new life. I wrote:

A summer is nothing in these mountains, a cloud is nothing, one more wing. So much for permanent weather, the light I learn to do without.

In its sense of loss, my poem isn't much different from Frost's, just as Frost's feelings of alienation and desire, as much as identification, brought him back to New England and Franconia. I'm remembering another poem, "Reluctance," the first Frost poem I found on my own. As a pragmatic 16-year-old, skeptical, angry, unhappy enough to believe it was my lot to reckon with loss as no one ever had, I'd found nothing of myself in the Frost poems my teachers declaimed poems like "The Road Not Taken." I failed a test on that one. Though I'd perfected the memorization, I couldn't see the poem as a metaphor for choosing the Christian life rather than the road which most probably led to sin.

The last stanza of "Reluctance," though, seemed to have nothing to do with the poetry my teachers taught. Ah, when to the heart of man Was it ever less than a treason To go with the drift of things, To yield with a grace to reason, And bow and accept the end Of a love or a season?

If I had to imagine the never-seen red-gold trees and fallen leaves, the seasonal reminder that Frost uses to bring home his love's failure, no matter. The last stanza's acknowledgment of grief joined my stubborn bitterness to someone else's, far away from sea-level Louisiana, from cotton and soybean fields. I walked around for days with those lines locked in my head.

"Stanza," the poet James Merrill reminded us, means "room" in Italian, and even in its freest form is a little apartment of thought, feeling, and image. It is a human connection (or lack thereof) that propels us there. Because of Frost, I'd found my way to a room I didn't know existed. Perhaps it was the belonging he could find in the house a poem makes, something beyond "the place where if you have to go there, they have to take you in" that Frost was after.

Frost made the farm in Franconia not a successful working operation but a home for the poems he knew he must write there. Gentleman farmer, old masquerader, he imagined the place rather than worked it. Donald Sheehan, director of the Frost Place for the past 18 years (and senior lecturer in the English and classics departments at Dartmouth) likes to tell the story of Frost staying awake all one July night to work on his poem "New Hampshire." As the sun began to rise behind the house, he walked out on Ridge Road and returned minutes later with "Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening" complete in his head. Not the old farmer pausing on the kind of ice-driven January night that farmers in those years fought in order to survive, but the poet filled with a night spent giving shape to words and lines. Inspired by the rising day, Frost found a metaphor for that work.

To think of poetry is to think metaphorically: saying one thing and meaning another. Saying one thing in terms of another. Yet, as Frost said, "All metaphor breaks down somewhere. That's the beauty of it. ..until you have lived with it long enough, you don't know where it is going." As I look back to my time in Frost's house, I see it as the representation of a writing life, a home for that life. The first place I felt the certainty of that writing self, the one I couldn't deny, was on his porch, where the three great mountains before me loomed, luminous in the dusk.

Understand that for me, the world of human beings, personal or public, was not my reference point. I was a Greek child with an absent Cherokee father in a Louisiana parish that recognized only black and white. I spoke another language, but it was the language of the kitchen, not the heart. To choose Greek was to choose certain alienation, but as I turned away, nothing welcomed me in that exclusive white southern life. I distanced myself, and though I loved books inordinately, I had no interest in their writers, southern or otherwise. I coveted only the verbal territory they inhabited, the great kingdom of language. My solace was landscape, my seemingly limitless freedom to roam the swamps and woods that went on for miles around our house. Later, when I began to write, the land was my connection to the deepest self and its dreaming center; mute and unyielding, it drove me to speak.

Lost to Louisiana, parentless, and lost parent of a new child, I sat on Frost's porch day after day as I now sit in the privacy of my Sanborn office with its familiar prints on the walls, my books, all the accumulation of my teaching and publishing life, and if nothing else is certain, I am committed.

An act of will, this commitment. I remind myself to be true to my intentions, to commend to my poems my entire spirit. Frost again: "Every poem is an epitome of the great predicament, a figure of the will braving alien entanglements."

Teaching, in some ways like writing, has everything to do with risk and discipline, but what he believed as a writer, Frost didn't trust to teaching. "Teaching by presence," his personal availability to aspiring writers, was enough for him. Language, form, rhyme: all were suspect; it was, in the end, fascination and not knowing which drove him. For the students, that process must be selflearned: "In finding out too much too soon, there is danger of arrest." I know this appeals to me because I've been such a slow learner: teaching has given me a language. Only after I wrote did I begin to find words for what I knew by intuition only.

Frost came to teaching as an old man, personally broken but poetically sure. He found several campuses that nourished him as his domestic life had not. At home he was never a very happy man, never secure in the love of his family, always fearful. But the letters to his students show him nourished by the bright circles of talk this place engenders; they reveal a teacher who could openly encourage, who could give away what he never feared he would lose. I've walked up to the third floor of Baker Library, to room 215, where Frost held his seminars and met with students. That room looks out on Dartmouth Row, a view that must have reminded him of the boy who escaped those buildings whenever possible, until stubborn, broken-hearted, he left the place entirely. With Elinor now dead and his grown children's sad lives a torment, how wrenching the path of his life must have seemed. Yet with equanimity, humor, and pride he gave certain assurance and encouragement to the young men who gathered around him.

In the pictures we have from those years, I'm struck by their absorption in what their teacher is saying, the slight smiles on their faces, the obvious pleasure in his company. As I am sure he felt in theirs. Frost said in one essay that he could

stay with a student all night if he could get "where he lives, among his realities." He knew that teaching pulls us away from the preoccupations of the lived life, and the lived life is truly what governs the work of a poet, whether he admits it or not. Frost's own realities were grim, yet he believed in the work his presence encouraged students to approach. Through his students, the art of poetry could be central in his life. He was forever comparing the art of writing with the art of living: "Life sways perilously at the confluence of opposing forces. Poetry in general plays perilously in the same wild place. It plays perilously between truth and make-believe." And then my favorite Frost quote: "The figure of a poem and of love are the same, begun in delighand ended in wisdom...a momentary stay against confusion."

Athome, domestic life reigns: I am mother, cook, and cleaner, and though I escape to my study, I do so with certain guilt for whatever task still needs attention. Emphatically, I shut the door on that life when I meet my students in Sanborn. My attention centers on literature, on the inner life and its necessities. Stillness lies at the heart of a good workshop—in the midst of voices, a listening. Fifteen years now I've listened to those voices, the young ones and the ones long gone from these halls and the Poetry Room, which the English department has graciously allowed me to appropriate for my workshops. And as I've grown to love that room with its three pictures of Ramon Guthrie, Robert Frost, and Richard Eberhart, I've taken on a life here that continues to surprise me with its loyalty and affiliation. In the same way that my real understanding of Frost began not with his language but by inhabiting the physical space of his home, my office in the basement of Sanborn has come to represent the sanctity of my creative life.

I haven't long been aware of this particular intimacy. A couple of winters ago I was asked if I wanted to move to the third floor the offices off the Shakespeare Room adorned with fireplaces and parqueted floors—and surprised myself with my fierce resistance. I realized that never in my life had I lived in one room for 15

years. Never had I owned one intensely selffilled, private place. Again and again I've walked from some generous seminar room through the open spaces of Baker Library and the lower corridor into my dim hall and had a rash of delight when I opened my door. Flooded with light, my room brings in the sun even in the darkest winter months. My window frames a perfect red maple, always the seasons' reliable indicator. I've watched that young tree grow from little more than a sapling.

My Sanborn office has come to signify my deepest, most abiding energy, that search into the language of the self. It's become another landscape, a home that I set out for all those years ago. My girl is a young woman now, still fond of the Frost poems she learned to say along with her favorite nursery rhymes. And I hope always to return to that room where she took me, to see his lovely cherry-wood rocker on the plain pine floor, his handsome picture on the desk beside it. Those days in his house were the beginning of a life. Fifteen years: I've settled in.

I avoided his things whenever possible, his study (preceding page), his cherry rocker (above), even his poems (right), which I loved.

I sat there, reluctant to go inside the silent house, daydreaming not of Frost but of all the past personal failures I felt constricted and defined by.

The real intimacy is something I've been able to recognize only as I've gotten older—the certainty that all of us struggle with alienation of some sort, both fearing it and fearing its defeat;

With the exception of the porch (above), everything about the Frost Place seemed austere, forbidding, even the mailbox (left).

Cleopatra Mathis teaches English and creative writing at Dartmouth. She was recently appointed faculty associatefor the East Wheelock Cluster. The Frost Place in Franconia, New Hampshire, is opento the public from June through Octoberfrom 1-sp.m. daily, except Tuesdays. Call (603) 823-5510f0r information.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

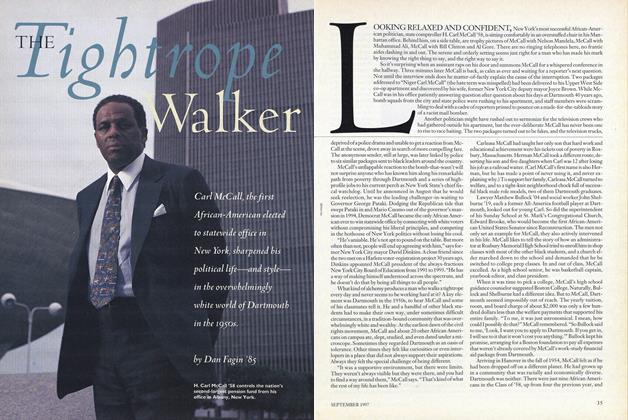

FeatureThe Tightrope

September 1997 By Dan Fagin '85 -

Feature

FeatureUninight

September 1997 By DOUGALD MACDONALD '82 -

Feature

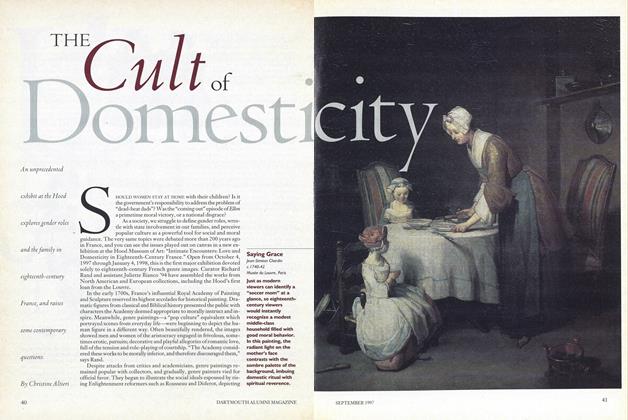

FeatureThe Cult of Domesticity

September 1997 By Christine Altieri -

Article

ArticleRoad Trip

September 1997 By Sarah Moore -

Article

ArticleElevator Going Up, AstroTurf Going Down

September 1997 By "E. Wheelock." -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

September 1997 By Noel Perrin

CLEOPATRA MATHIS

Features

-

Feature

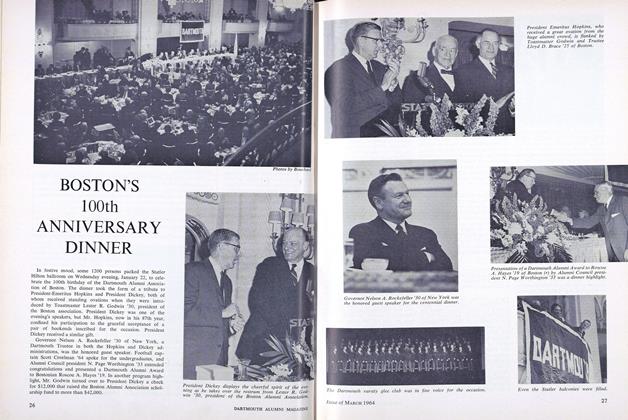

FeatureBOSTON'S 100th ANNIVERSARY DINNER

MARCH 1964 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWOOD AND CANVAS CANOE

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

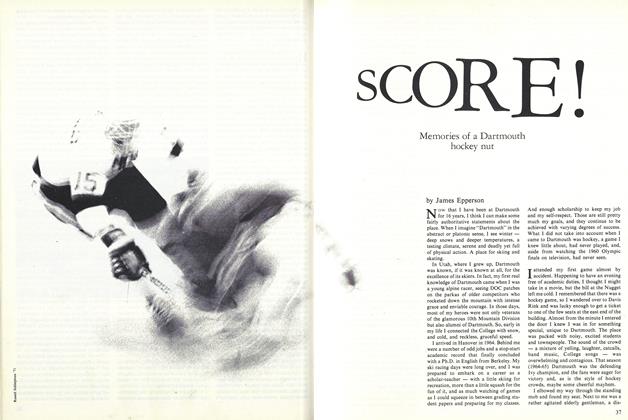

FeatureSCORE!

JAN./FEB. 1980 By James Epperson -

Feature

FeatureStaying Clear

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jeanet Hardigg Irwin '80 -

COVER STORY

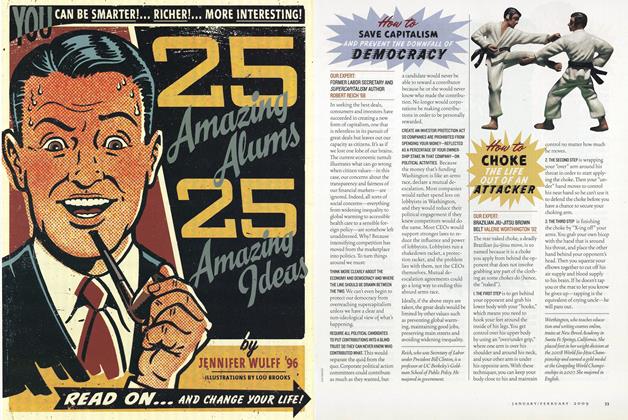

COVER STORY“Take This Advice Today!”

Jan/Feb 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

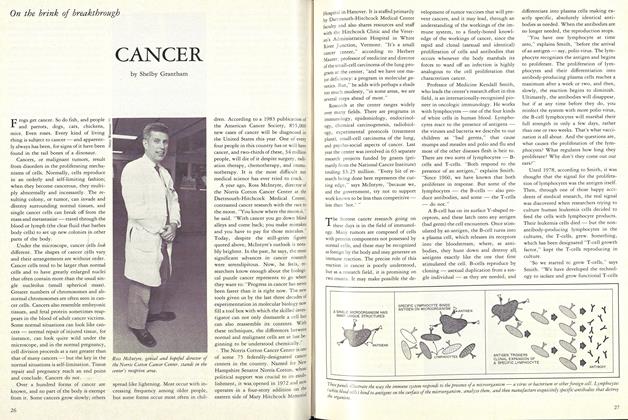

Cover StoryCANCER

APRIL 1983 By Shelby Grantham