Carl McCall, the first African-American elected to statewide office in New York, sharpened his political life and style in the overwhelmingly white world of Dartmouth in the 1950s.

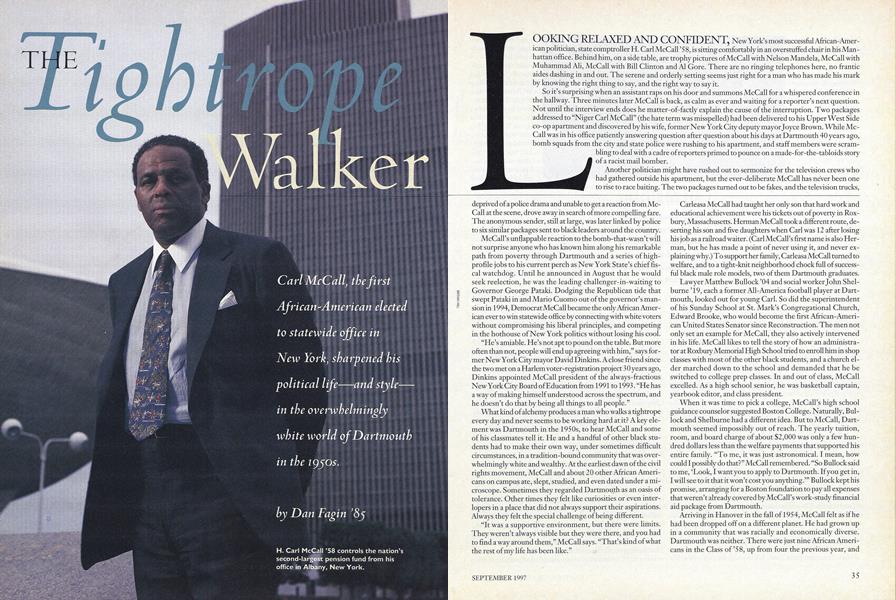

Looking relaxed and confident, New York's most successfal African-Amere comptroller H. Carl McCall' 58, is sitting comfortably in an overstuffed chair in his Mannd him, on a side table, are trophy pictures ofMcCall with Nelson Mandela, McCall with IcCall with Bill Clinton and A1 Gore. There are no ringing telephones here, no frantic and out. The serene and orderly setting seems just right for a man who has made his mark right thing to say, and the right way to say it.

So it's surprising when an assistant raps on his door and summons McCall for a whispered conference in the hallway. Three minutes later McCall is back, as calm as ever and waiting for a reporter's next question. Not until the interview ends does he matter-of-factly explain the cause of the interruption. Two packages addressed to "Niger Carl McCall" (the hate term was misspelled) had been delivered to his Upper West Side co-op apartment and discovered by his wife, former New York City deputy mayor Joyce Brown. While McCall was in his office patiently answering question after question about his days at Dartmouth 40 years ago, bomb squads from the city and state police were rushing to his apartment, and staff members were scrambling to deal with a cadre of reporters primed to pounce on a made-for-the-tabloids story I of a racist mail bomber.

Another politician might have rushed out to sermonize for the television crews who had gathered outside his apartment, but the ever-deliberate McCall has never been one to rise to race baiting. The two packages turned out to be fakes, and the television trucks, deprived of a police drama and unable to get a reaction from McCall at the scene, drove away in search of more compelling fare. The anonymous sender, still at large, was later linked by police to six similar packages sent to black leaders around the country.

McCall's unflappable reaction to the bomb-that-wasn't will not surprise anyone who has known him along his remarkable path from poverty through Dartmouth and a series of highprofile jobs to his current perch as New York State's chief fiscal watchdog. Until he announced in August that he would seek reelection, he was the leading challenger-in-waiting to Governor George Pataki. Dodging the Republican tide that swept Pataki in and Mario Cuomo out of the governor's mansion in 1994, Democrat McCall became the only African American ever to win statewide office by connecting with white voters without compromising his liberal principles, and competing in the hothouse of New York politics without losing his cool.

"He's amiable. He's not apt to pound on the table. But more often than not, people will end up agreeing with him," says former New York City mayor David Dinkins. A close friend since the two met on a Harlem voter-registration project 30 years ago, Dinkins appointed McCall president of the always-fractious New York City Board of Education from 1991 to 1993. "He has a way of making himself understood across the spectrum, and he doesn't do that by being all things to all people."

What kind of alchemy produces a man who walks a tightrope every day and never seems to be working hard at it? A key element was Dartmouth in the 19505, to hear McCall and some of his classmates tell it. He and a handful of other black students had to make their own way, under sometimes difficult circumstances, in a tradition-bound community that was overwhelmingly white and wealthy. At the earliest dawn ofthe civil rights movement, McCall and about 20 other African Americans on campus ate, slept, studied, and even dated under a microscope. Sometimes they regarded Dartmouth as an oasis of tolerance. Other times they felt like curiosities or even interlopers in a place that did not always support their aspirations. Always they felt the special challenge of being different.

"It was a supportive environment, but there were limits. They weren't always visible but they were there, and you had to find a way around them," McCall says. "That's kind of what the rest of my life has been like."

Carleasa McCall had taught her only son that hard work and educational achievement were his tickets out of poverty in Roxbury, Massachusetts. HermanMcCall took a different route, deserting his son and five daughters when Carl was 12 after losing his job as a railroad waiter. (Carl McCall's first name is also Herman, but he has made a point of never using it, and never explaining why.) To support her family, Carleasa McCall turned to welfare, and to a tight-knit neighborhood chock fall of successful black male role models, two of them Dartmouth graduates.

Lawyer Matthew Bullock '04 and social worker John Shelburne '19, each a former All-America football player at Dartmouth, looked out for young Carl. So did the superintendent of his Sunday School at St. Mark's Congregational Church, Edward Brooke, who would become the first African-American United States Senator since Reconstruction. The men not only set an example for McCall, they also actively intervened in his life. McCall likes to tell the story of how an administrator at Roxbury Memorial High School tried to enroll him in shop classes with most of the other black students, and a church elder marched down to the school and demanded that he be switched to college prep classes. In and out of class, McCall excelled. As a high school senior, he was basketball captain, yearbook editor, and class president.

When it was time to pick a college, McCall's high school guidance counselor suggested Boston College. Naturally, Bullock and Shelburne had a different idea. But to McCall, Dartmouth seemed impossibly out of reach. The yearly tuition, room, and board charge of about $2,000 was only a few hundred dollars less than the welfare payments that supported his entire family. "To me, it was just astronomical. I mean, how could I possibly do that?" McCall remembered. "So Bullock said to me, 'Look, I want you to apply to Dartmouth. If you get in, I will see to it that it won't cost you anything.'" Bullock kept his promise, arranging for a Boston foundation to pay all expenses that weren't already covered by McCall's work-study financial aid package from Dartmouth.

Arriving in Hanover in the fall of 1954, McCall felt as if he had been dropped off on a different planet. He had grown up in a community that was racially and economically diverse. Dartmouth was neither. There were just nine African Americans in the Class OF '58, up from four the previous year, and McCall remembers hearing grumbling that Dartmouth had "lowered its standards" in more than doubling the number of black students admitted. Later Dartmouth classes would have as few as one black student, and the numbers would grow very slowly in the 1960s before rising steeply in the early 1970s.

The sense of separateness felt by the black students was exacerbated by the College's freshman housing policy. It was the year of U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education, and the country was alive with debate over the segregation issue, or "the negro problem" as it was called at the time. But in 1954, only one of the nine black freshmen at Dartmouth was assigned a white roommate by the College, and the exception, Harcourt Dodds '58, thought his assignment might have been a mistake. Later, as president of the dormitory council, McCall would help change the freshman rooming policy in the first ofhis many ventures into racial politics. But when they were freshmen, the College's racebased housing assignments—which administrators at the time described as an effort to make black students feel more "comfortable" were merely a topic of conversation in McCall's circle, not a political cause. Indeed, some of the black students were grateful for the policy. "It was such an overwhelmingly white environment, I think it almost seemed like a break to live with ANOTHER BLACK STUDENT, says Dodds.

McCall and the other black students could, of course, room with whomever they wanted after their first year. But almost all of them decided to continue to live with one another, even as they scattered into various fraternities, sports, and organizations across the campus. "Because we were so relatively few in number, we did have a tendency to coalesce around each other," Dodds says. "We'd look for each other in the dining hall. We'd trade information on where the girls were, because there were relatively few black girls in the schools around the Northeast. We spent a lot of time together."

One chip at a time, the black students carved out carefullycircumscribed niches at Dartmouth. McCall had one of the busiest chisels. He played on the freshman basketball team under Coach Al Maguire, who would go on to fame as a Marquette. coach and national television broadcaster. McCall joined Gamma Delta Chi and became active in student government. Because Edward Brooke and most other black leaders in Massachusetts were Republicans, McCall even joined the College Republicans—a decision that has since prompted playful needling from Governor Pataki, his political rival.

As the African-American students moved to join the mainstream, President John Sloan Dickey and the rest of the administration took some steps mostly small ones to make them feel welcome. Thurgood Marshall and Roy Wilkins of the NAACP were invited to Hanover to lecture on civil rights. "Doggie" Julian started two blacks on the basketball team at a time when many comparable schools were relegating their black players to the bench. And Garvey Clarke '57 remembers how moved he felt when the student body in early 1954 (a few months before McCall arrived on campus) voted overwhelmingly to require fraternities to drop their affiliation with nationals that had racially or religiously restrictive charters. Like most other significant changes at Dartmouth in those years, the disaffiliation process was excruciatingly gradual, and wasn't completed until after McCall and the rest of the class of '58 had already graduated.

McCall and his black classmates were constantly put in the position of representing their race to people who frequently had never conversed with a black person before. "There were some white fellows who really got it, and we got to be really good friends despite ethnic differences. But for the most part we were like a novelty. You got the sense you were pretty much always on stage," says Gene Booth '57. "I can remember frequently being asked in social settings things like, 'What do you think you should do about the negro problem?' And I can recall quite vividly saying, 'I don't have a negro problem.'"

The same anxieties about representing a cause greater than themselves also led the black students to be careful about what they said and did on campus, "It was just certain" automatic protocol," says Booth. "We all followed it." Interracial dating, for example, was practically unheard of, and no one complained when certain fraternities never extended bids to African-American students even after the houses had nominally dropped racist membership restrictions.

In such a carefully-proscribed atmosphere, McCall developed a non-confrontational personal style that would serve him well later on. "Carl was always the kind of person who was very diplomatic, very politically astute. He had a certain regal nature, but he was also very friendly and warm," says Clarke. A. Robert Towbin '57, who is white, remembers McCall's calm persuasiveness. "He was a guy who was a little different than the other students. He was going to study theology. He was a real thinker. Invariably, when the conversation would get around to the black-white problems, he would always, without getting emotional about it, have a point of view that was interesting and intelligent. A militant black guy would have the same point of view, but Carl had a way of expressing it that just sounded like it would be easier to sell coming from him."

Despite the alienation they sometimes felt, the African Americans on campus never took on Dickey and the rest of the administration in those years. "Dartmouth had a very small contingent of blacks, and they were just glad to be there. It wasn't a big enough group, like you had later, for people to become involved in protesting and questioning the way the institution operated," McCall says. Nor did he and his friends jump on buses to join the boycotts and marches that were just beginning in the South, as would so many of the next generation of Dartmouth students. "We were part of the silent generation, just like everybody else," says Dodds.

Now McCall makes a point of urging New York companies to increase their minority hiring, but as a graduating senior he didn't press the issue when he found that Dartmouth was abetting a recruiting process that excluded blacks from jobs at top banks and corporations. As state comptroller, McCall is the sole trustee of an $88 billion state pension fund (the nation's secondlargest), the chief auditor of state and local governments, and the man who decides whether New York's budget and borrowing practices are fiscally sound. But as a graduating senior, he couldn't even get an interview for a bank training program. "Recruiters would come and I never saw them, even though I kept signing up," McCall remembers. "I finally had a discussion with someone in the administration who was responsible for setting up interviews, and he just told me that the people who were coming to recruit were not interested in black students. That was just sort of closed off as an option. I felt that was a point where the College did not serve me well, and that I was not really a part of the mainstream. But, I've got to tell you, I let it go. I didn't push it. Now black students wouldn't accept that, and shouldn't accept that."

Making his own connections, McCall did just fine. After getting his divinity degree, he moved to New York City and became the activist he never was at Dartmouth. He worked for various civil rights causes in the 19605, and in 1974 was elected as Harlem's representative to the New York state senate. Four years later, President Jimmy Carter appointed him the United States' second-ranking diplomat to the United Nations. After losing a race for lieutenant governor in 1982, McCall bided his time in private industry, working as a vice president of Citibank and running the city board of education, an unpaid position. The chance he was waiting for came in 199 3, when New York's longtime comptroller resigned. Though lacking experience in accounting and finance, McCall used his political connections and his reputation as a talented manager to win appointment by the State Legislature to fill the unexpired term, and in 1994 won a fall four-year term from state voters. Three years later, as New York's pension fund climbed toward $90 billion, former governor Hugh Carey called McCall the "most popular investor in the country."

His relations with Dartmouth have not followed quite so straight a path. A founding member of the Black Alumni of Dartmouth Association, which celebrated its 25 th anniversary in May, McCall steered a series of promising Harlem students to the College just as Matthew'Bullock and John Shelburne had guided him a generation earlier in Roxbury. But like many African American alums, McCall wasn't happy with what he heard and read about the College during the 1980s, when The Dartmouth Review was making headlines for its vitriolic attacks on affirmative action. "I gotvery turned off, as a lot of people did," he says.

What turned McCall back on again was an encounter with Dartmouth President James O. Freedman in 1988, just after the election of George Bush as President. By that time, McCall was at Citibank, and Freedman was speaking at a reception for Dartmouth graduates who worked at the bank. Someone asked Freedman what he would tell the newly elected President if Bush asked him what his top priority should be. "I'll never forget this. Freedman's answer was that he would say to Bush that he's got to increase opportunities for minority students in higher education, that the future of our country, really, depends on our ability to provide educational opportunities for minority students. I thought that was really impressive, because he wasn't talking to the Urban League or the NAACP. In fact, I think I was the only black person there. This was a group of white executives who he was trying to solicit support from. So I felt good about the school again, from his statement and from what I came to learn about him."

Until August 7, when he announced he would not try to unseat George Pataki, McCall had been traveling around the state, delivering speeches that were a little less cautious than usual, with sharper digs at Governor Pataki and other Republicans. Often he worked Dartmouth into his stump speech, telling audiences that he is a living example of the worth of providing opportunities for minority students, including affirmative action programs.

What he doesn't tell his audiences is that one of the things he learned at Dartmouth was how to thrive in a community that, when viewed from today's perspective, did not always live up to its own ideals. "It was clear to us that discrimination was very real, and that we were victims of it. But we were in the mode of, 'You have to work harder. You have to be better. You have to overcome.' And that's what we did."

H. Carl McCall '58 controls the nation's second=largest pension fund from his office in Albany, New York.

On the Line In the early 1960s McCall, left, fought to open the New York construction trades to African Americans. At a rally in Brooklyn, he was joined by Garvey Clarke '57 (in hat).

Life Line While at Citibank, McCall and his wife, then-New York City deputy mayor Joyce Brown, built bridges between Wall Street and Nelson Mandela's fledgling democracy.

DAN FAGIN '85 reports on the environment for Newsday and is the co-author of Toxic Deception (Birch Lane Press, 1997). He is former editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

September 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Feature

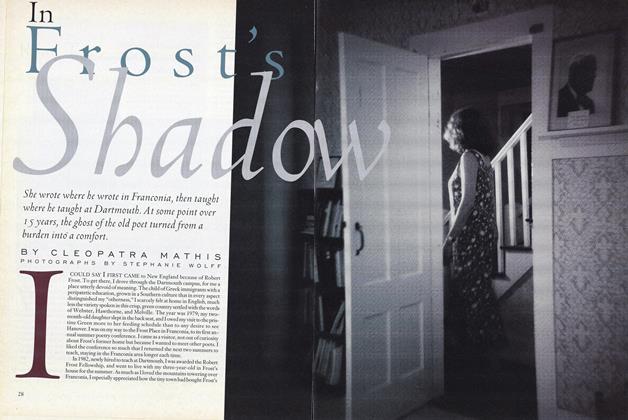

FeatureUninight

September 1997 By DOUGALD MACDONALD '82 -

Feature

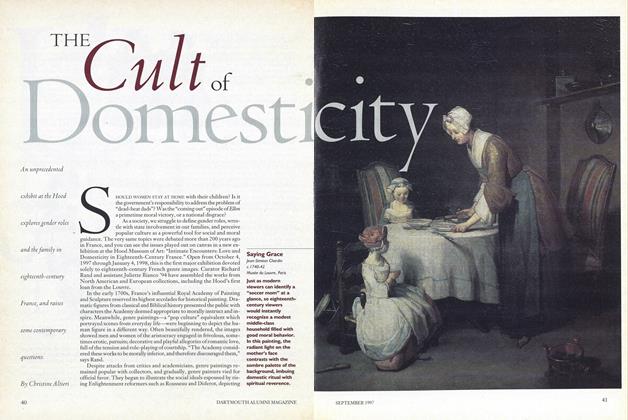

FeatureThe Cult of Domesticity

September 1997 By Christine Altieri -

Article

ArticleRoad Trip

September 1997 By Sarah Moore -

Article

ArticleElevator Going Up, AstroTurf Going Down

September 1997 By "E. Wheelock." -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

September 1997 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

OCTOBER, 1908 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureSafe Haven

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

COVER STORY

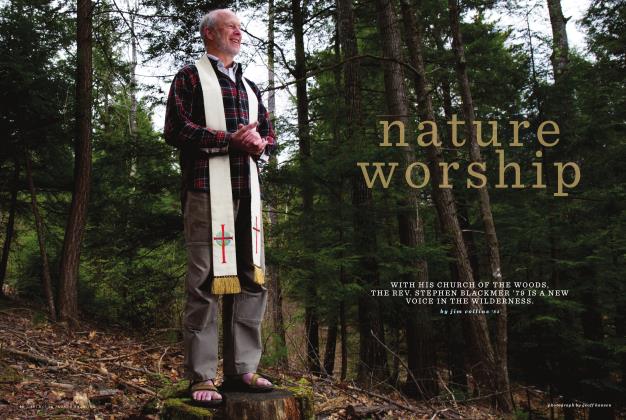

COVER STORYNature Worship

MAY | JUNE 2019 By jim collins ’84 -

Feature

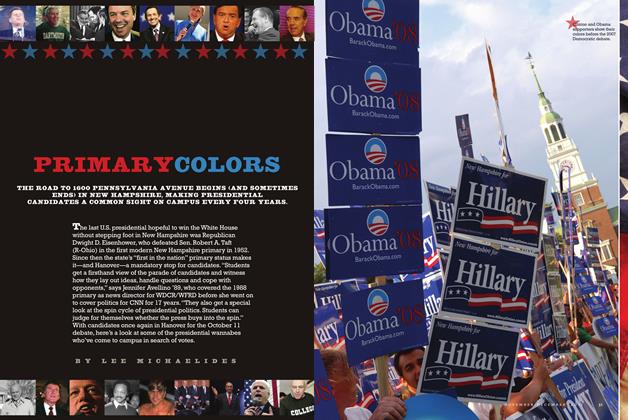

FeaturePrimary Colors

Nov/Dec 2011 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

DECEMBER • 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT