From the Model T to the 4 x 4, our obsession with the car has defined who we are and where we're going.

When the Duryea brothers of Springfield, Massachusetts, sold the first commercial car in 1896, no one imagined how profoundly the new product would reshape America. The car would come to drive how we build our towns, how we do our business, why we fight wars, even how we define ourselves. "Today, the idea that you are not really a citizen until you have your own car is rooted in our culture," says history professor Ron Edsforth in his course "The Automobile and The American Way of Life."

pie initially resented cars because only the very wealthy could afford them. The first automobile boom started in 1908 with the production of Ford's Model T. The first mass market for the Model T was farmers, many of whom got into their vehicles, drove off the farms, and never came back. "Farm work was hard, and it was seven days a week," says Edsforth, chief historian for last year's PBS series America on Wheels and author of the book Auto Work. "The farm was not a place where young people wanted to be, so they got into their cars and left." Many of the young men ended up in mass-production jobs in auto factories. When the industry replaced the hand crank with the Americans didn't always have a love affair with the car, says Edsforth. Most peo- self-starter, young women joined men in using cars to assert a new and mobile independence.

World War II put the brakes on America's car culture but left an enduring effect on the looks of the car. Designers like General Motors's Harley Earl drew inspiration from fighter planes. Airplane stabilizers became fins, twin engines became bumper protuberances, and cockpits metamorphosed into curved windows and dashboards filled with dials. In such a car, any American could be a hero.

The 1950s brought a surge in what the historian James Flink calls "automobility." Services for drivers gas stations, fast food restaurants, motels, and gift shops popped up along the American roadways. Cities created parking lots and commercial zones. "Before the era of the automobile the towns were zoned for multi-use," says Edsforth. "Now there were specific streets on which no one was allowed to park."

By the 1960s America was speeding along interstate highways, doing business at one-stop shopping malls and drive-thru windows. But the increasingly car-driven landscape had a noticeably detrimental effect on our social interaction. As James Howard Kunstler points out in The Geography of Nowhere, the built environment led to antisocial public behavior. In towns like Hanover that were built before the car, people routinely walked, shopped, and met one another downtown. Convenient, parkingfriendly shopping strips drew shoppers out of town and ran over ambiance. "Would you go there for a stroll or a meaningful conversation?" asks Edsforth. "Of course you wouldn't. These are the most alienating places in the United States:" The blossoming highway culture impacted everything from downtown economies to commercial architecture to land-use and population patterns.

Many Americans didn't realized how car dependent they had become until the early 1970s when the OPEC oil crisis brought the nation's blase gas-guzzling to a screeching halt. Americans initially responded by climbing into smaller, more fuel-efficient cars, but a decade later the popularity of bigger cars was on the rise. The number of the nation's cars has doubled in the last 25 years and, and, as a society, we are more car dependent than ever. People are living farther from where they work, shop, and go to school. And we are paying the price. In addition to pollution, the land toll alone for parking our cars is staggering. "I read in The New York Times recently that there's something like seven or eight parking spaces for every vehicle in the United States," Edsforth says. "We are literally paving things over." And that's just the surface of the problem. If the price of oil were to soar again, Edsforth warns, the nation would be thrown into economic chaos. "We've already seen the evidence that the federal government will do almost anything to keep that price of oil down, including going to war," he says. "That's what the Gulf War was about. We are a civilization that depends almost completely on the price of one commodity. Any change in supply or demand could undermine life as we know it."

But most Americans have more personal mileage on their minds when they reach for their car keys. Edsforth argues that, in addition to status and identity, cars give an important sense of power to individuals who feel less and less control over their lives. "Cars give us a way to put a skin around ourselves that projects a different image of who we are," he explains. Image even outdistances economics. "If people bought cars for economically rational reasons, they really wouldn't buy the kinds of cars that sell the most. They certainly wouldn't buy two-ton trucks to drive back and forth to the supermarket. In my mind, the only intelligent way to buy a car is to buy it for the transportation, with the least amount of credit, and run it into the ground." Edsforth, by the way, drives a Ford Escort.

Students find his course unsettling. "They come into class as people who love cars and see them as something wonderful," he says. "They haven't considered the enormous environmental costs of their large, fashionable, sport-utility vehicles." Once they have to confront the facts that bigger cars take more energy to produce, are less efficient, do more damage to the roads, and are harder to dispose of—and once they see the social costs of our society's dependence"they can no longer look at their cars, or America, in the same way."

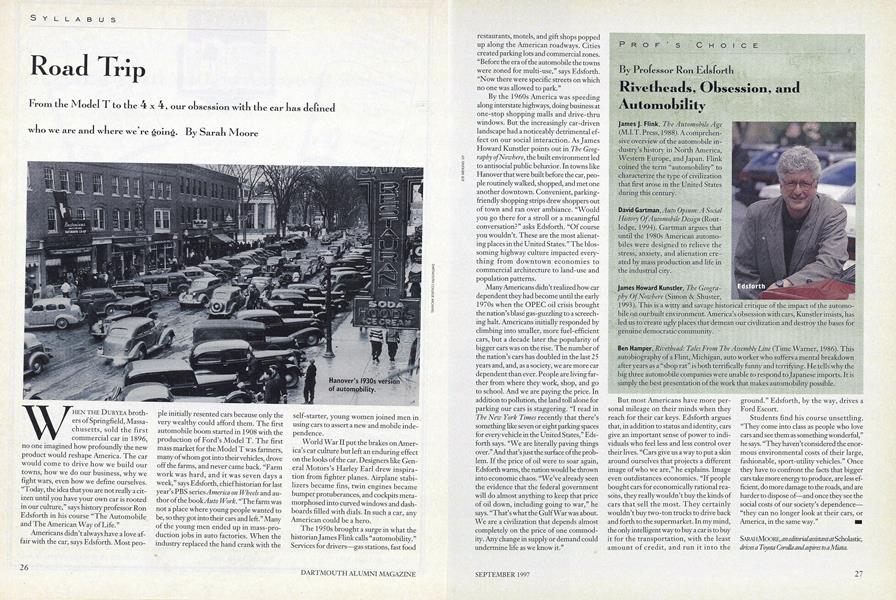

Hanover's 1930s version of autompbility.

SarahMoore, an editoiial assistant at Scholastic. drives a Toyota Corolla and aspires to a Miata.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

September 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Feature

FeatureThe Tightrope

September 1997 By Dan Fagin '85 -

Feature

FeatureUninight

September 1997 By DOUGALD MACDONALD '82 -

Feature

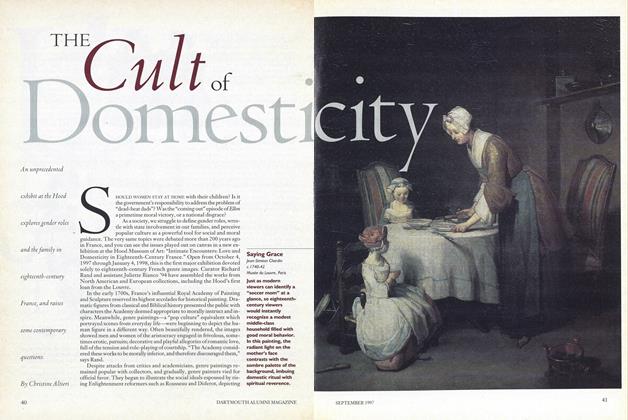

FeatureThe Cult of Domesticity

September 1997 By Christine Altieri -

Article

ArticleElevator Going Up, AstroTurf Going Down

September 1997 By "E. Wheelock." -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

September 1997 By Noel Perrin

Sarah Moore

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR JOSHI TEACHES COMPARATIVE RELIGION COURSES

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

ArticleIn video Veritas

APRIL • 1985 -

Article

ArticleNot So Fine

DECEMBER 1998 -

Article

ArticleGrads

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Meg Menon Hansen -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH SCIENTIFIC ASSOCIATION, ITS ORIGIN AND HISTORY

May 1916 By Charles F. Emerson -

Article

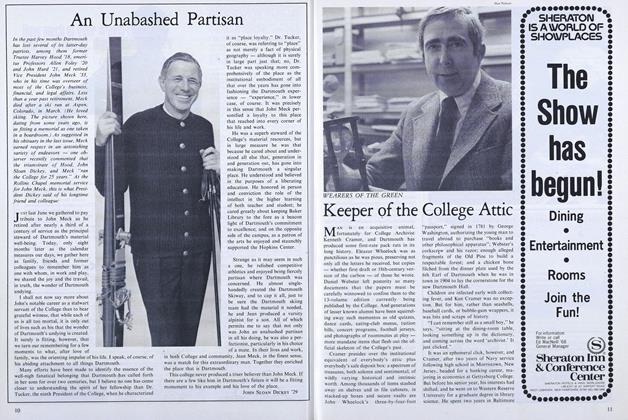

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

MAY 1978 By M.B.R.