Nurturing Nature

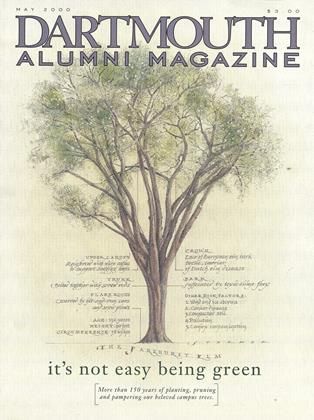

Trees do not grow on campus by chance. For more than 150 years the College has planted, pruned and pampered its precious trees—all 1,146 of them.

MAY 2000 Richard OberTrees do not grow on campus by chance. For more than 150 years the College has planted, pruned and pampered its precious trees—all 1,146 of them.

MAY 2000 Richard OberTrees do not grow on campus by chance. For morethan 150 years the College has planted, pruned andpampered its precious trees—all 1,146 of them.

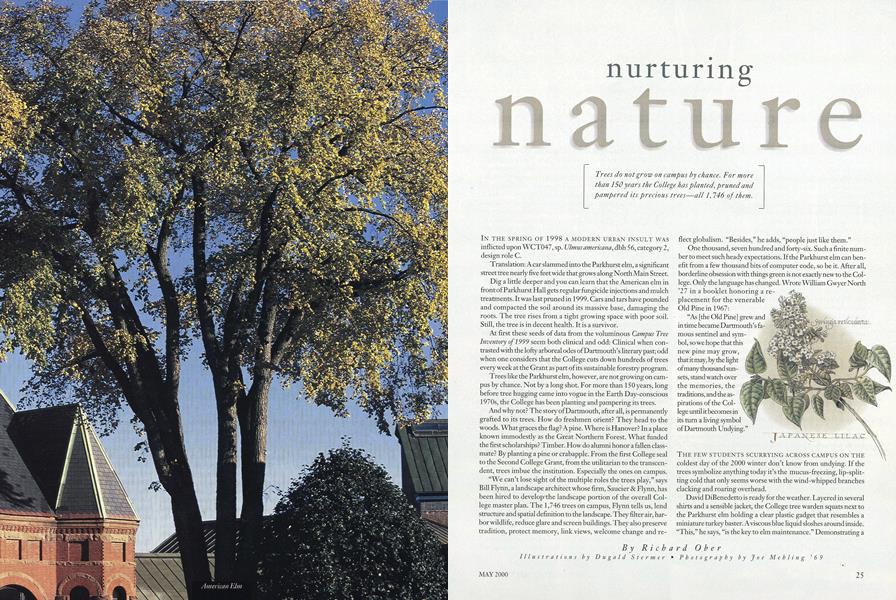

IN THE SPRING OF 1998 A MODERN URBAN INSULT WAS inflicted upon WCT047, sp.Ulmus amertcana, dbh 56, category 2, design role C.

Translation: A car slammed into the Parkhurst elm, a significant street tree nearly five feet wide that grows along North Main Street.

Dig a little deeper and you can learn that the American elm in front of Parkhurst Hall gets regular fungicide injections and mulch treatments. It was last pruned in 1999. Cars and tars have pounded and compacted the soil around its massive base, damaging the roots. The tree rises from a tight growing space with poor soil. Still, the tree is in decent health. It is a survivor.

At first these seeds of data from the voluminous Campus TreeInventory of 1999 seem both clinical and odd: Clinical when contrasted with the lofty arboreal odes of Dartmouth's literary past; odd when one considers that the College cuts down hundreds of trees every week at the Grant as part of its sustainable forestry program.

Trees like the Parkhurst elm, however, are not growing on campus by chance. Not by a long shot. For more than 150 years, long before tree hugging came into vogue in the Earth Day-conscious 1970s, the College has been planting and pampering its trees.

And why not? The story of Dartmouth, after all, is permanently grafted to its trees. How do freshmen orient? They head to the woods. What graces the flag? A pine. Where is Hanover? In a place known immodestly as the Great Northern Forest. What funded the first scholarships? Timber. How do alumni honor a fallen classmate? By planting a pine or crabapple. From the first College seal to the Second College Grant, from the utilitarian to the transcendent, trees imbue the institution. Especially the ones on campus.

"We can't lose sight of the multiple roles the trees play," says Bill Flynn, a landscape architect whose firm, Saucier & Flynn, has been hired to develop the landscape portion of the overall College master plan. The 1,746 trees on campus, Flynn tells us, lend structure and spatial definition to the landscape. They filter air, harbor wildlife, reduce glare and screen buildings. They also preserve tradition, protect memory, link views, welcome change and refeect globalism. "Besides," he adds, "people just like them."

One thousand, seven hundred and forty-six. Such a finite number to meet such heady expectations. If the Parkhurst elm can benefit from a few thousand bits of computer code, so be it. After all, borderline obsession with things green is not exactly new to the College. Only the language has changed. Wrote William Gwyer North '27 in a booklet honoring a replacement for the venerable Old Pine in 1967:

"As [the Old Pine] grew and in time became Dartmouth's famous sentinel and symbol, so we hope that this new pine may grow, that it may, by the light of many thousand sunsets, stand watch over the memories, the traditions, and the aspirations of the College until it becomes in its turn a living symbol of Dartmouth Undying."

THE FEW STUDENTS SCURRYING ACROSS CAMPUS ON THE coldest day of the 2000 winter don't know from undying. If the trees symbolize anything today it's the mucus-freezing, lip-splitting cold that only seems worse with the wind-whipped branches clacking and roaring overhead.

David DiBenedetto is ready for the weather. Layered in several shirts and a sensible jacket, the College tree warden squats next to the Parkhurst elm holding a clear plastic gadget that resembles a miniature turkey baster. Aviscous blue liquid sloshes around inside. "This," he says, "is the key to elm maintenance." Demonstrating a springtime ritual, he aims the baster's sharp end at the base of the tree and smacks the bulb with a hammer. The tree's phloem—the layer of tiny vertical feeding tubes in the cambium layer just under the bark—sucks the blue fungicide up through the trunk in a matter of minutes. It is preventive medicine to fight Dutch elm disease.

DiBenedetto straightens and pockets the tool. Circling the tree, he points out how the thick flare roots bulge into North Main Street on one side and the sidewalk on the other. "Look at that. Here's this huge tree growing in a tiny spot of grass. No other tree but an elm could exist here." Nor could this one without Dartmouth's aggressive elm program. Every year DiBenedetto and assistant-tree warden Walter Schwartz prune dead branches and fertilize the roots. Every three years they dose the elm with fungicide. Several years ago they drove a long bolt clear through the massive trunk to prevent a vertical seam from splitting the tree in two. A spider's web of cables knits together the upper branches. Splotches of hardened black goo show where wounds have been sealed to keep out disease.

"Most institutions decide it's too expensive to maintain an elm like that," DiBenedetto says. "The whole campus, the whole town, was once covered with elms. There were hundreds of them. Now there are only about a hundred." The College, he explains, has no intention of giving up on these remaining elms, despite the expense: A single tree like the Parkhurst elm costs around $400 a year to maintain, not including staff time. Overall, the College spends approximately $130,000 annually to maintain its campus trees.

DiBenedetto knows it takes that kind of money. For 15 years before coming to Hanover, he worked as a contract arborist in Westchester County, New York, where rich homeowners easily drop 50 grand a year on trees and landscaping. Among his wards was the famous Bedford Oak, which is more than 600 years old. To this day the white oak remains his favorite. "I love the elms, but the oak is just such a beautiful, extending, magnificent tree. There are only a few on campus, but I know every one," he says almost bashfully.

Hanover, according to DiBenedetto, is not much different from New York when it comes to the incremental stresses that plague urban trees. "This is a tough place for trees. You're taking them out of their organic setting and sticking them into an urban environment. They get exposed to salt, exhaust fumes, dogs, compaction, jack hammers, cars, construction. You're also talking about poor soils here. Take an oak tree, for instance. The oak likes well-drained soil, and we're sticking it into clay." As tree warden, DiBenedetto's job is to make the best out of these less than ideal conditions. To do that he uses fertilizer and shovels and chemicals, pruning saws and stakes and cables and climbing ropes. And a lot of patience. "It can get a bit discouraging," he admits.

In his struggle with the elements, his prime tool is the campus tree database, which DiBenedetto helped compile by inspecting every tree on campus. He and Schwartz poked and prodded and measured and climbed and judged. Back in the shop they tapped their notes into the computer. Number. Name. Size. Health. Site conditions. Design roles. Maintenance schedules. And endless details: Hemlocks at Tuck have spider mite damage. Most of the pines near Alumni Gym have damaged roots. Some trees at the medical campus were planted too close to buildings. Construction damage at Baker is serious. Roadside lindens look sooty. Leaf spot is the scourge of campus crab apples, while leaf scorch hits red oaks. Aphids chew. Leaf miners mine. Hearts rot and mowers maim. Storms tear off limbs.

With so much data just a mouse click away, the inventory has become indispensable. The computer program integrates an exhaustive database with photographs, digitized maps of 21 separate sections of campus, and computer-assisted design technology. With it, DiBenedetto can track the maintenance regimen of an individual tree or all 80 species. He can retrieve a color picture of the Parkhurst elm and delete branches to see how it will look after a heavy pruning. He can call up a section map and check the overall health of trees on, say,' "Tuck Campus" or the "Original Campus." From information on soils and other environmental factors embedded in the program, he can pick good sites for alums to plant future memorial trees.

Fighting disease is also much easier. If DiBenedetto finds evidence of locust disease on one tree, for example, he can boot up the computer and instantly locate all locusts on campus before mounting his counter-attack. If he needs a certain fungicide, he can calculate how much by totaling the cumulative size of all the locusts. If a class planted a locust 30 years ago, he can help a curious alum find it.

The inventory is especially helpful in planning construction projects. Still stinging from the controversial sacrifice of a revered elm beside Baker Library a few years ago, campus architects can now anticipate problems ahead of time simply by consulting the inventory. "We've had circumstances where the architects have changed plans to save a single tree," DiBenedetto says with satisfaction. "In front of Rockefeller and Silsby, they re-routed service trenches and walkways to minimize root damage to two old elms. And along Tuck Drive, the inventory and maps helped prove that relocating the water lines would avoid damage to root systems."

Flynn, whose firm developed the inventory, consults it constantly for big-picture planning. Trees and plants, he has recommended, should be one of three overarching themes in future planning, the other two being acceptance of Hanover's essential "urbanness" and the imperative of maintaining order and spatial definition. To illustrate, Flynn cites two relatively young sugar maples that flank the grassy steps at Burke chemistry laboratory. Planted specifically to define and frame the front entrance, the trees reflect the strong influence of Central Park designer Frederick Law Olmsted, who used trees as symbols of power as well as practical elements in the landscape. Problem is, one of the maples suffers from a bleeding canker and both are plagued by a bug called the leaf cutter. Flynn is keeping an eye on them and will ask DiBenedetto to replace them with two new maples when they falter. He is also using the inventory's mapping and visual functions to show the seminal role that elm trees play at Baker Lawn and other key spaces in the central campus.

"The campus grounds are an integral part of the identity that Dartmouth is trying to project," Flynn says. "Part of the role of the trees is to help reinforce that traditional character."

ELEAZER WHEELOCK WOULD have embraced Flynn's first point and been horrified by the second. Raised under the Puritan ethic that saw forests as dark and evil, Wheelock beheld the sylvan Connecticut Valley in 1769 as a "horrid wilderness" that needed to be tamed. The first job was to kill the trees and create a "simple and wellordered clearing in the wilderness."

Towering white pines fell, buildings rose and tie Green emerged as a sunny icon of man's pre-eminence over nature. But dominance is hard work in northern New England's stubborn forest. The Green became the central organizing element of campus only when it had finally knuckled under to the regimen of plow, plantings and fence. Every class through 1820 was expected to pull another stump from the intemperate ground.

In the mid-19th century, Puritanism gave way to the Romantic embrace of wildness, and trees came into fashion. Town and campus officials oversaw the ordered planting of elms about the Green while amateur arborists such as mathematics professor John E. Sinclair stuck saplings wherever they liked.

When the College hired landscape architect Charles Eliot in 1893, campus trees took on dimensions beyond the aesthetic. An Olmsted protege, Eliot used trees to soften the inhuman scale of buildings and address complex social, cultural and environmental issues. Issues there were. College President William Jewett Tucker's ambitious expansion plans meant more students, more buildings, more demand for modern amenities. The trees suffered. Gas for lighting hissed through leaky underground wooden pipes and poisoned roots. The first tar walkways in 1886 sealed the soil. New construction squeezed out planting spaces.

To maintain a balance, the town and College hired the first tree warden in 1901. He planted and pruned and painted tar over wounds. The elms in particular responded to this care. Tough as weeds and resistant to urban insults, their green and willowy crowns reached out to embrace the stern white and brick buildings. The resulting effect would, in the words of Robert Davis class of 1903, "make anyone's heart skip a beat." Returning to campus in 1936, Davis gushed: "The geometric buildings, the wine-glass trees, were as detached as enamelled toys upon a nursery background....Rarely do the human senses receive an impression so flawless."

Biology professor Charles J. Lyons was equally smitten by the scene, if not a bit less sanguine about its permanence. In a 1937 article in this magazine, he predicted major changes and losses in tree populations, especially the elms. Lyons wasn't barking up the wrong, well, you know. A shipment of elm burls from Europe had recently arrived in the United States carrying a stowaway fungus called Ceratocystis ulmi-pathogen of the deadly Dutch elm disease. Over tire next several decades the epidemic would kill more than 100 million American elms across the country. One by one, most of the great Dartmouth elms succumbed. Some trees died within weeks of exposure, leaving gaping holes in the College's landscape—and its psyche.

"The elms' decline compromised the spatial integrity, character and identity of the campus," Flynn writes in a recent report on preservation strategies for the campus. "The charm of the 19th century residential village gave way to a modern, institutional complex."

Unwilling to let such dramatic change contribute to the degradation of the lovely Beaux Arts campus, College planners redoubled efforts to balance natural and man-made features. By the time DiBenedetto was hired in 1993, Dartmouth's tree program was considered on a par with such academic arboretums as those at Middlebury, Swarthmore, Vassar and Harvard. And its elm program was unequalled anywhere.

Mary K. Reynolds, urban forester for the state of New Hampshire, has been assisting College tree wardens since the mid-19705. "I just love Dartmouth and I visit whenever I can," she says. "It's probably our best example of a cold-hardy arboretum in the northeastern United States." (Reynolds also helped Hanover secure its status as a Tree City USA, a program coordinated by the National Arbor Day Foundation.)

"We are committed to maintaining the trees as long as we can," says grounds supervisor Bob Thebodo, who was tree warden for 13 years and is now DiBenedetto's boss. "Even if we can buy just one year for an important tree, we're going to do it."

STEPHANIE EDWARDS '00, FOR ONE, IS GLAD OF THAT. Like DiBenedetto, she's partial to oak trees, although her favorites are the reds. "I love the oaks outside Russell Sage and on the rest of Tuck Drive," she says. "They turn beautiful shades of red and gold in the fall."

In the future, Edwards and tree lovers across campus will be able to download the tree inventory from the campus Web site. That would allow a curious beech bum, for example, to learn that her favorite trees fruit to nuts rather than to pods or pomes, are pollution tolerant and relatively pest-free. Gingko groupies looking for a fine specimen of that ancient gymnosperm will want to head over to the Blunt Alumni Center lawn to commune with WCT 091 (West Campus Tree #91). College fundraisers working inside Blunt might note that the Grace family favors crab apples when dedicating trees to a loved one. The Corbins prefer white pines. Big tree huggers can search for a 50-inch silver maple to wrap their arms around. President Wright could research the history of the noble row of Norway spruce behind Bones Gate. And Edwards would be relieved to find that her favorite tree, an "absolutely timeless and gorgeous oak" in front of Butter field, will likely be replaced with another pin oak when it eventually dies.

As, of course, all trees do. Even trained arborists hate to see beloved old ones die. Thebodo admits it stills breaks his heart every time.

Lots of people feel that way about the Parkhurst elm. They can take heart, however. Thebodo and DiBenedetto already know that when it goes they will plant in its place another elm, either trucked down from Canada or transplanted from the organic farm, where the College is growing disease-resistant Liberty elm saplings. That's because the inventory pegs the Parkhurst tree as a Category 2: "A tree of aesthetic and/or spatial value. Category 2 trees should be replaced with the same species if it is important to maintaining the integrity of the original design." (Not quite as secure as a category 1 tree—but a lot better off than category 4, trees which are "incidental" and have "minimal or little impact." A 4 is pretty much taking up space. When it's gone, it's gone.)

Isn't it a bit daft to decide now that one stressed-out elm will be replaced with another, especially when the species demands a level of health care beyond that available to many human beings? Why not plant a less risky kind?

To answer that, Flynn and DiBenedetto bring you back to the Green. Look north toward Baker Lawn, where campus planners of the 19th century planted perfectly straight columns of elms. See how the wonderful "wine glass crowns" frame the buildings. Notice how the trees define the lawn as an important space and unify the library with the Green. Picture what Commencement used to be like under those arching branches.

As Dartmouth changes, its arborists, like other officials, straddle a thin limb between the traditional and the contemporary. How does the campus evolve and respond to contemporary needs? How does it reflect new values while also respecting historic integrity and character? For now, their plan is to retain elms as the defining tree of central campus—no matter the cost—while experimenting in other key places with splashes of color and new botanical ideas. Thus the Kentucky coffee tree, the gingko, the yellow wood, the Kwanzan cherry, the tatsura tree, the Japanese pagoda tree, the Korean mountain ash, the European euonymous. Trees selected not only for their distinction and beauty, but for their hardiness in northerly climes.

These colorful new varieties don't have to compete with Dartmouth's woody monarchs. There's room for both. Elms and maples and oaks to root the institution in its natural environment and rich past; intriguing new varieties to welcome change. In another context, another place, this metaphor might sound like so much psycho-pagan mumbo-jumbo. Here, however, where the landscape is one with the College Zeitgeist, it's serious stuff.

History. Character. Power. Globalization.

And you thought they were just trees.

JAPANESE LILAC

WHITE PINE

Crabapple

Red Maple

White Birch

Norway Spruce

Elms along Dartmouth Row, circa 1948

Reel Maple

Elms at north end of the Green, circa 1948

White Ash

David DiBenedettoCollege Tree Warden

Crabapple

Kousa Dogwood

The College spends about $130,000 annually to maintain its campus trees.

Trees reinforce the traditional character of the College.

"This is a tough place for trees. You're taking them out of their organic setting and sticking them into an urban environment."

RICHARD OBER is a senior staff member with the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests and editor of the quarterly journal Forest Notes. His work has appeared in Outside, Northern Woodlands, Tree Farmer and other magazines. His last anicle for DAM, about logging in the Grant, appeared in the October 1998 issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

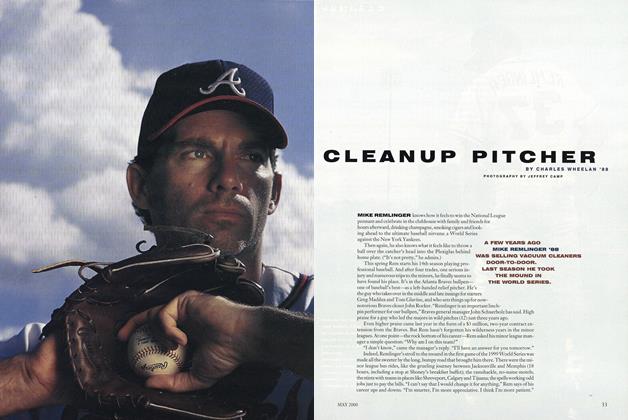

FeatureCleanup Pitcher

May 2000 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

May 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Private Lives of Public People

May 2000 By Jennifer Avellino ’89 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSScreening Reality

May 2000 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Excellence

May 2000 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleYou Are Here

May 2000 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSeeing Farther than the Green

September 1976 By BLISS K. THORNE and NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

OCTOBER 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Train Robbery

June • 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureYesterday: A Policy of Consumption

April 1974 By GORDON J. F. MacDONALD -

Feature

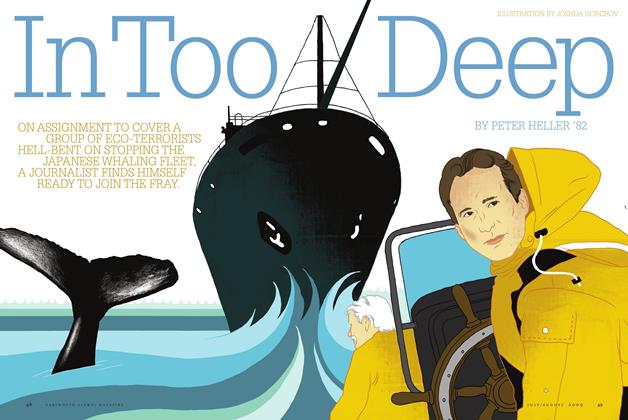

FeatureIn Too Deep

July/Aug 2009 By PETER HELLER ’82