MASTER, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, OXFORD UNIVERSITY

THE subject we are discussing this afternoon is "Issues That Arise from the Democratic Processes in the Three Countries." I assume that we are not concerned with particular issues, such as arose over Suez, but with the difficulties which the democratic processes may place in the way of our achieving a common policy when such issues do arise.

Last year when Sir Roger Makins was still the British ambassador in Washington he delivered an address entitled TheConduct of Foreign Policy in a Modern Democracy. He pointed out that in the field of foreign affairs the democratic governments were under certain handicaps when compared with the totalitarian ones. He said: "The thirst for popular information about the conduct of foreign policy, the constant questioning of an eager and vigilant press, the critical supervision of legislators, mean that governments are forced to explain their policies more fully than may be desirable from the point of view of effective negotiation." The danger, he concluded, is that policies may be declared before full judgment can be made. In particular the totalitarian governments have the advantage of maximum flexibility as they need not play in the open and are not subject to criticism and advice at home. On the other hand they suffer from two major disadvantages; in the first place they are handicapped by misinformation as their representatives hesitate to give them unfavorable news, and in the second place their mistakes may be catastrophic owing to lack of criticism. . . .

In Great Britain Parliament is supreme. The Ministers are the servants of Parliament and can be dismissed by it at any time. This is obscured by the fact that these servants are given complete responsibility for the conduct of all government affairs as long as they remain in office. There can, therefore, be only a single official foreign policy at any one time, although, of course, there may be conflicting views within the Cabinet. The complete power given to the Ministers is controlled by their duty to account to Parliament immediately for their acts. Question-time which occupies the first hour of every sitting day except Friday is the most striking feature of the Parliamentary system, for the Government is then subject to a form of cross-examination. . . .

This system functions admirably at ordinary times, but it gives rise during a crisis to some of the dangers to which Sir Roger Makins referred. The Prime Minister may be forced to declare a policy which had better remain unformulated for the time being. It has been suggested that this was one of the difficulties during the Suez crisis. The public debate may also encourage a foreign opponent by emphasizing the division of opinion in the House. Its greatest disadvantage is that it may tend to cause hesitancy on the part of the Government for fear that it may fall before it is able to carry its policy to a conclusion. This is true in particular if the Government has only a small majority which it is in danger of losing. In these circumstances the democratic process encourages an uncertain foreign policy rather than a strong one.

In the United States the powers of Congress and of the Executive in the conduct of foreign affairs are independent, although they must, of course, be exercised in coordination if they are to prove effective. Congress is supreme in enacting any necessary laws, especially the all-essential appropriation of money. On the other hand the President is supreme in the conduct of foreign affairs, especially in his control, as commander-in-chief, of the armed forces. As there must be coordination between the two independent powers, the strain on the President and his Secretary of State becomes a rapidly increasing one. Thus Mr. Dulles has pointed out that a great part of his time is spent attending an ever-increasing number of Congressional committees which may be covering nearly the same ground. The machinery is becoming so complicated that it is almost unworkable. . . .

There need be no uncertainty, however, in so far as the President's conduct of his own independent part in foreign affairs is concerned. He need not give any explanations at the time concerning his actions, and he need not obtain the support of Congress for them. The resolution which the President asked Congress to vote at the time of the Quemoy crisis was of no practical value, although it was of importance from the propaganda value as showing that the contemplated use of force had the support of the nation. A President can therefore take a greater risk in embarking on a course which may be temporarily unpopular than can a Prime Minister, because the former can hope that time will justify his acts before the final accounting: in the case of a Prime Minister such an accounting may be called for at any moment. Thus, to take one illustration, it is most unlikely that Abraham Lincoln would have been able to conduct the American Civil War to a successful conclusion if he had held office under the .British or Canadian systems. . . .

It is not my purpose to attempt any comparison of the efficiency of the British and American processes as shown in the relation between the legislature and the executive. It is clear, however, that the differences between them may give rise to difficulties unless they are clearly understood. It is also clear that in neither case can the machinery be regarded as foolproof: it must always depend on the sense of responsibility and the soundness of judgment of those who work it.

When we turn to the second democratic process as exemplified by the relationship between the government as a whole and the public at large, as represented by the voters, there is again a striking difference between the British and the American systems which may not be sufficiently recognized at present.

in Great Britain the Prime Minister and the other Ministers are the servants of Parliament and are directly responsible to it. During the War Churchill emphasized on a number of occasions that, as this was the position he held, the House was free to dismiss him at any time, but until it did so it was responsible for his acts. It follows therefore that it is the primary duty of the Prime Minister to explain his actions to the House so as to obtain its approval before he does so to the country at large. The House of Commons therefore bitterly resents any attempt to by-pass it by a previous announcement to the press. Press conferences, as they are conducted in the United States, are therefore almost unknown in Great Britain, and would not fit into the British constitutional set-up. If the Prime Minister, or one of the other Ministers, is to be questioned this must be done in Parliament....

On the other hand, in the United States the President is the servant of the people, being elected by them and directly responsible to them. Neither he nor his Cabinet officers are directly responsible to Congress although the latter can be questioned by the various Congressional committees. The modern press conference, as it has developed in recent years, is therefore a natural, and not an artificial, part of the Amer- ican system because it enables the President to report di- rectly to those whom he represents. As far as one can judge, it is here to stay. But because its origin is a comparatively recent one it has not as yet developed more than a rudi- mentary technical procedure.

It is with the greatest diffidence that I suggest that some consideration might be given in the future to the technique of Parliamentary question-time. It is important that notice of the question must be given beforehand, although in the case of private notice, this may be comparatively brief. It is therefore impossible for the Minister to have a question sprung on him which he has not had time to consider. This is an advantage, especially where international affairs are concerned, as an answer which has not been sufficiently weighed, may give rise to misunderstanding. Sometimes an answer, given on the spur of the moment at a press conference, may also reveal something which it was not the intention to disclose at that time, thus causing embarrassment to other persons.

The second technique of Parliamentary question-time concerns the supplementary questions which are directed to elucidating the original answer. When well-handled these may be of the greatest value in bringing out all the relevant facts concerning a particular situation. A study of the full reports of the press conference in Washington suggests that the questions are rarely cumulative or relevant to each other. As a result the conference, however entertaining it may be, does not exercise the full influence of which it is capable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

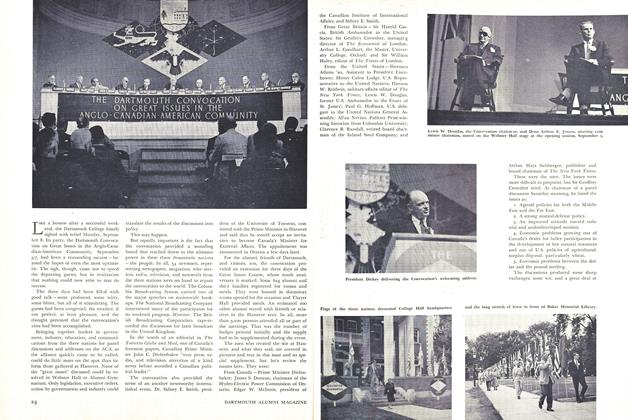

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Dollop of Yankee Talk

February 1961 -

Feature

Feature"I Am Having a Wonderful Time"

DECEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureExtracurriculn Vitae

January 1975 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Christgau's Ear Turns '51

April 1993 By BILL GIFFORD '88 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Balance

MAY 1997 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureStrangers in a Strange Land

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13