The news of a born-again greasy spoon reminded the author of an unsettling truth Hanover is just not that kind of town anymore.

BECAUSE I LIKE FOOD AND TROUBLE and I'm always surprised to see a good Yankee go South, the recent appearance of the Streamliner Diner in Savannah, Georgia, caught my interest. The Streamliner had once been a Hanover landmark. From its perch on Allen Street it served locals, members of the Hopkins Center construction crew, and countless students through both peacetime and war. (Even Lewis Bressette '27A, owner of the once-rival and still operating Lou's Restaurant, dined there.) The diner vanished, without much fanfare, from Hanover in 1958.

The details of the Streamliner's story, I learned, were gothic (one owner died; another had a mental breakdown), nostalgic (a Lou's employee bought the diner in 1957 just to keep it in town), Confederate (it got sold at an Atlanta auction), and even revivalist (it was born again!). I wish it had been around in my day. I don't know how many hours it would have saved me driving and drooling to the Four Aces in West Lebanon and the Hartford Diner in White River. The fact of the matter is this: the Streamliner could have been the quintessential Dartmouth College diner.

HANOVER, DURING THE 18 YEARS the Streamliner was there, was a diner town. Folks from around the area came in to shop for hardware and household goods and plain home cooking. The Streamliner was just one of several diners students visited. "I remember the Streamliner. It was right off Main Street," Burton Bernstein '53 told me. "But I favored Hap and Hal's. It was near C & G. I took Dylan Thomas there when he was in town because it was the only place he could get a drink. Hanover was a dry town then, and they'd sell you nickel beers under the counter at Hap and Hal's." Brock Brower '53 told me that he ate more often at Lou's or Mac's. "They used to have price wars with one another," he said. Another popular spot was the White Owl.

As diners go, though, the Streamliner was the real thing, a genuine dining car company restaurant manufactured by Massachusetts' Worcester Lunch Car Co. circa 1938. It offered that year's classic details: stained-glass monitor windows, an arched barrel roof, shiny black-and-red-tile floors, and seating for 36, counting the oak booths and stools lining the mauve marble counter. Its exterior was Dartmouth green.

According to a buffet of history provided by Lewis Bressette, diner historian Richard Gutman, and American Diner Museum curator Daniel Zilka, the Streamliner was owned by three now-deceased local men, two of them brothers. One brother died in the mid 19505, the surviving brother had a mental breakdown, and the third man decided to pull out of the business. Lou's employee Bob Conrad bought the diner in 1957 to try and save it, but gave up on the business within a year. The Streamliner got moved down Route 10 to Newport, New Hampshire, where it was attached to Billy's Diner and renamed the Newport Diner. Meanwhile, Ray and Velda Dickinson opened the Midget Diner as a 13-seat diner on Alien Street that used the Streamliner's kitchen, which apparently was left behind since the Streamliner-as-Newport-Diner could use the kitchen from Billy's. The Midget survived for 14 years. (I called the Dickinsons to talk about the Midget. "Velda! Lady on the phone writing about diners," yelled Ray. Velda got on the phone and said, "I would say the restaurant was 99 percent students. For help mostly we had students. We had a lot of Psi U boys and Tri-Kap boys and it all worked out nicely. We only had 13 stools. We had Sunday night specials, like spaghetti with homemade fried bread. They used to line up around the corner on Sunday nights. I don't really know how we made any money.")

Ahh, money. Bigger and Bigger Green. Money is the reason that the Streamliner or any diner for that matter couldn't operate nowadays in Hanover if it tried. (Bigger and Bigger Green is the reason I'm a business journalist and not a fulltime reclusive fiction writer.) It isn't easy maintaining an old-style diner, as the above restoration experts and articles in diner enthusiast magazine Roadside report. A typical restoration including structural work and decorative facelifts on antique porcelain enamel, steel, and neon surfaces can run up to $250,000, a sum not easily recouped with short stacks of flapjacks and cheap joe. Add to that the warming real-estate climate in Hanover, and it's clear that no new diners will be moving to town any time soon. According to Bruce Waters, a commercial broker with McLaughry Associates, property costs in Hanover's commercial district have escalated so much over the past 15 years that even the Grand Union supermarket's one-acre plot on Main Street fetched $1.4 million in a recent sale. "If anything," says Waters, "Hanover will probably continue upgrading its restaurants. A lot of pressure in Hanover now comes from the retirement community. And Dartmouth students have enough money to spend on fine dining." The restaurants coming to Hanover these days are trendy and upscale, serving latte and tiramisu.

Of the old restaurants, only Lou's remains. Bressette offers one reason why his restaurant has stayed in business for so long while others like the Streamliner have passed: "They probably served the same type of food that we served, only ours is a little bit better."

But the Streamliner, ironically, might have had a chance. The Newport Diner was purchased in 1987 by a diner broker and eventually sold to the Savannah College of Art and Design along with a Rhode Island diner named Bobbie's for $260,000. The Streamliner's relocation to Savannah occurred shortly before SCAD, as the campus is nicknamed, received a "Deco Defender" award for its work purchasing and restoring historic buildings throughout the Georgia city. John Berendt, who chronicled Savannah's art-and-antiques community in his bestseller Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, gave a nod to SCAD President Richard Rowan for his help in restoring the downtown.

Not all diner fans were pleased. According to John Baeder, who has devoted his artistic career to depicting diners in Hopperesque, photorealistic paintings, the Streamliner had been beautiful when he first encountered it in 1978. In his book, Diners, he wrote, "The best BLT came to me across a slab of shiny marble. This was definitely close to Nirvana." By the time the diner had reached its new home in Savannah, though, he wrote, "Its new environment didn't seem real. It was plopped down on a corner in a questionable location. Standing by the entrance was a guard, with a gun, and all that."

According to reports in restaurant journals, the revived diner served gourmet hot chocolate and coffee and extra-fresh cuts of meat and was a place where the blue-collared rubbed elbows with the paint-splattered. By the sounds of it, the diner could have stood up against the upscale restaurants in today's Hanover. But then, according to SCAD master's graduate Jeff Breen, despite the architectural integrity of both the Streamliner and Bobbie's, SCAD moved to institutionalize food service in both restaurants, which caused much student grumbling over the diners' lost charm. "I recently asked for cheese grits and they brought me instant with a slice of American on top," said Breen, a native Virginian who knows grits. "There ain't no lovin' in that cookin' anymore."

Of course, diner owners have historically done a variety of things to make ends meet, from building additions and back rooms to embellishing the menu with increasingly high-priced specialties. The sad truth of diners in the 1990s is this: a diner isn't just a serendipitous home away from home; it's a business in a world where business is getting tougher.

The Streamliner left Hanover before I was born but had arrived in Savannah by the time I graduated. My special wish for the restaurant is that, bythetime my next reunion rolls around, the College will reclaim that Yankee diner from Savannah's deco downtown and install it on our tidy New England campus where students and locals can run the place and steam it up with old-style grease. I'd move it myself, but I'm no business-woman just a plump and occasional daydreamer.

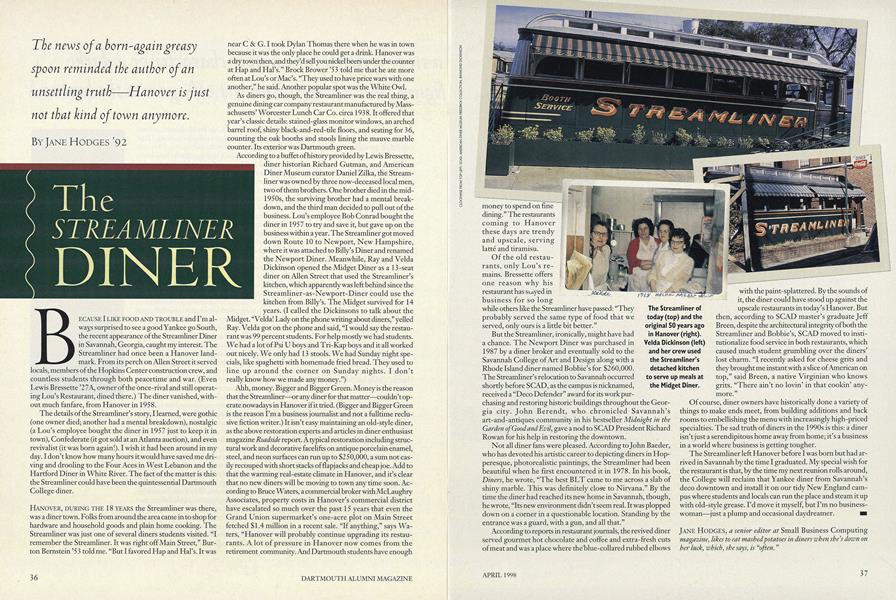

The Streamliner of today (top) and the original 50 years ago in Hanover (right). Velda Dickinson (left) and her crew used the Streamliner's detached kitchen to serve up meals at the Midget Diner.

JANE HODGES, a senior editor at Small Business Computing magazine, likes to eat mashed potatoes in diners when she's down on her luck, which, she says, is "often."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

April 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureSpiked Boots and the End of an Era

April 1998 By Edie Clark -

Feature

FeatureA Change in the Weather

April 1998 -

Article

ArticleThe Benefits of a College Town

April 1998 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

April 1998 By John MacManus -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

April 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89

Jane Hodges '92

-

Article

ArticlePanting For Credit

MARCH 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleSeniors Interview Their Elderly Future Selves

MAY 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleWe asked 53 students: "Would You Send Your Child to Dartmouth?"

June 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleGreen Behind The Screen

September 1992 By Jane Hodges '92 -

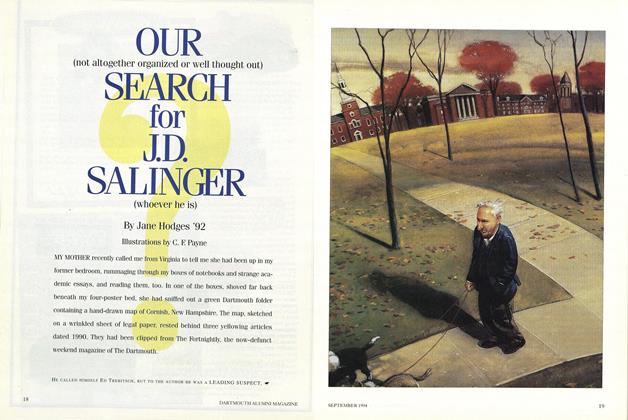

Cover Story

Cover StoryOUR SEARCH FOR J.D. SALINGER

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Jane Hodges '92 -

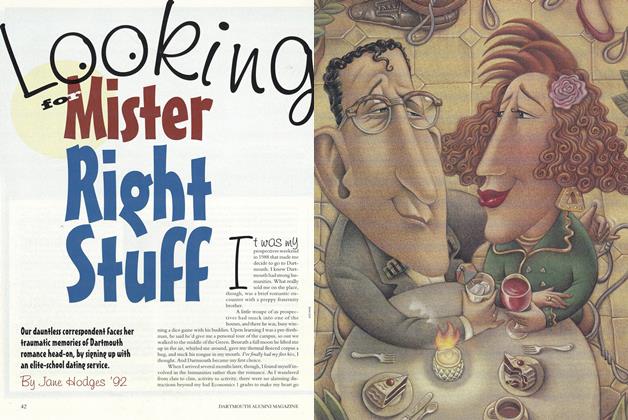

Feature

FeatureLooking for Mister Right Stuff

Novembr 1995 By Jane Hodges '92

Features

-

Feature

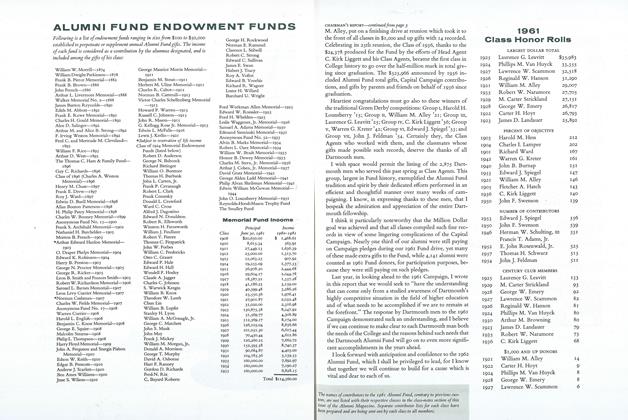

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

November 1961 -

Feature

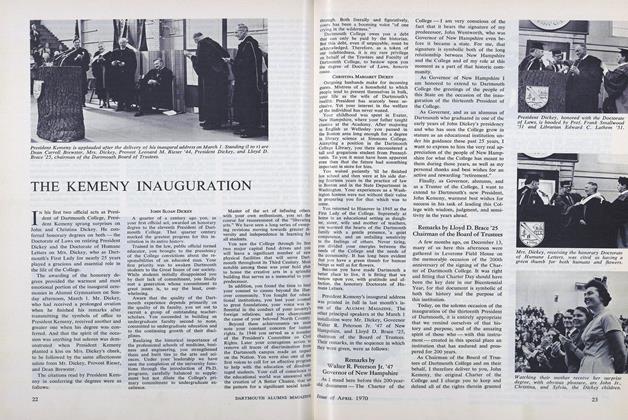

FeatureTHE KEMENY INAUGURATION

APRIL 1970 -

Feature

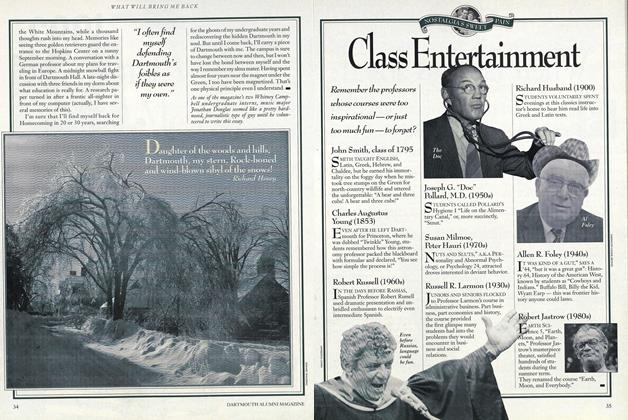

FeatureClass Entertainment

MARCH 1991 -

Feature

FeatureModern Family

September | October 2013 By ALEC SCOTT ’89 -

Feature

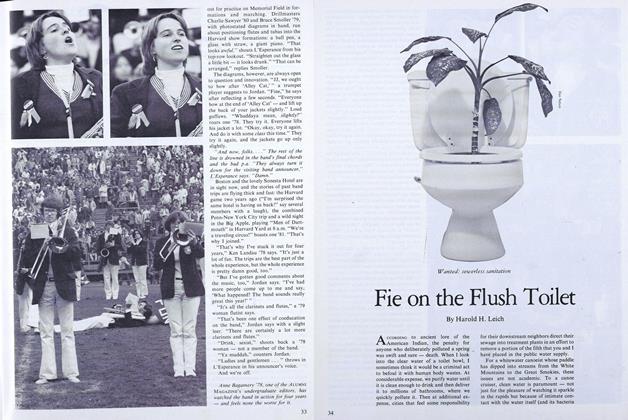

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

NOV. 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMater Dearest

MARCH 1997 By Regina Barreca '79