OXFORD IS A GOOD PLACE TO BE LONELY. I used to think the very landscape breathed loneliness, the courtyards exhaling mist, longing for company. I was wrong. Oxford needs no one, no life to complete it. The old buildings are glorious and indifferent their limestone faces turning gold in the occasional sun, their stone monsters grinning, eyes fixed and wary. The lush lawns roll like carpets, the skyline holds its pose of spires, and, without fail, the bell towers chime and toll the quarter-hour, one after another all over the city. It could be a museum exhibit, unaware of the crowds that daily swarm its cobbled streets. It could be a ghost town, oblivious to the petty comings and goings of its 15,000 students, even to that select group of Americans known as Rhodes Scholars. All our self-important struggles simply drifted away in the evening fog, as we changed courses and "fought the system" and debated endlessly why we were here, whirling without purpose in the medieval centrifuge of Oxford. Although I lived in it for nearly two years, the city always existed apart from me. This is the trouble with History: you can't touch it or move it, you can't make it personal.

At first I felt I was in a novel. I spent hours wandering immaculate gardens, oblivious to the rain misting on my face. Everything was luminous and green in the wet. I stood on an arched bridge and watched two swans glide along the narrow black river a tiny river, more of a stream, its mirrored surface reflecting the hanging trees. Someone told me that Kenneth Grahame had written The Wind in the Willows right here, overlooking the same dark water. And Dylan Thomas once lived in the gardener's shed along the path to my room. I felt enormously, unfairly privileged, and knew I'd been chosen for this life by sheer accident: at any moment the Rhodes Committee would realize its mistake and summon me back home. The college was full of mysteries, wrought-iron gates that my key wouldn't open, stone staircases spiraling up to high tower rooms. Somewhere they kept 14 words from the original Gospel of Matthew, and supposedly beneath everything lay a huge maze of caverns, cold vaults of vintage wine for the Fellows.

For a few days I was in love with my new life. Organ music floated from the chapel and echoed in the Cloisters. A herd of deer grazed and barked softly in the meadow out back. I loved walking to the covered market to buy fruit and black tea sharp red apples, loose darjeeling and jasmine. In the market stalls, the cut flowers overflowed their bins and sent sweet fragrance drifting down the aisles, mixing with smells of meat pies and hot bread. I'd never seen such perfect flowers, fresh from the countryside or the Continent creamy Devon pinks and Dutch freesia, six colors of glistening tulips, and tiny roses in deep shades of orange. I had to resist buying a bouquet each time I passed. Even after the original magic had faded and unhappiness blurred my whole vision of Oxford, I didn't stop savoring those market trips, although I could then count on one hand the good things about England: apples and tulips and tea.

The grace period ended when I had to go to tutorial. At the same time the weather turned hostile, the short days grew steadily darker. A bitter wind moaned from the East, blowing hard out of Siberia and sweeping before it our Indian summer, hot cloudless afternoons with the gardens still blooming and the trees raining down yellow leaves. Battered by horizontal rain, I trudged across college to my tutor's room, my essay on Marlowe safe inside my coat. Chestnuts dropped like stones into the river and the ducks floated headless, beaks tucked under their wings. The sight made me ache with homesickness. I would have done anything then to get out of tutorial—an interminable hour alone with David Norbrook, awkward and brilliant and utterly incomprehensible to me. I would talk about poetry in my impressionistic way as he tried to steer me toward a more hard-edged, academic approach to the lit- erature. I perched on the slippery leather couch and looked at my hands; he sat amidst piles of books and papers and frowned at my essay, alternately clearing his throat and adjusting his glasses. "But what did the word 'invention' mean in the Renaissance?" he finally hinted. "Think of inventio, of the terms of Rhetoric..."

I never caught his leads, having no background in classics or theory or much of anything besides contemporary American poetry. We spoke different languages, and he was helpless to translate Oxford for me, to explain even the basic requirements and expectations of my Course. Overwhelmed by a barrage of obscure, essential jargon—Mods, Finals, Collections, Commentary, Translations, Two-one, First—l took my confusion personally and deemed myself inadequate. I had a writer's passion without the critic's intelligence, a worthless combination in this place. Several times I left his room on the verge of tears, frustrated and humiliated. Later I would learn that this was all part of the Oxford Mystique, an initiation rite whereby first-year students are intentionally kept in the dark by the University, until they begin to uncover, over months, its archaic workings on their own. The humbling process is most effective for those who have furthest to fall. American Rhodes Scholars, long familiar with the paths to success at their alma maters, are caught for the first time without the answers.

I don't know when exactly the change came, only that by November I was rooted deep in my sadness. In December a cloud descended on Oxford for days, a dank gray blanket that settled on the buildings, muffled the streets. I could feel the weather inside me, damping me down. I would walk home from the Bodleian library on cold evenings with my bag of books, the air raw against my face, the bell towers slowly tolling ten. Inside the college gates lay a heavy quiet, broken only by my clogs echoing along the flagstones. Mist rose in the courtyards and drifted through stone archways, hanging in the ancient Cloisters. My life felt delicate and impossible, as if it were a story written for another character or a dark landscape painting I kept wandering through, small figure in the foreground, set off against the lawns.

"I don't know how to live here," I told my parents. I didn't want to go back after Christmas vacation. There was nothing for me in Oxford besides rain and David Norbrook, who had politely requested we read Richardson's Clarissa over a million words, the longest novel in the English language. But when I got off the bus from the airport in January, I found a changed world. Oxford was flooding. The once-tame rivers overflowed their banks, lapping at underbrush, drowning the tree-trunks. I put on my running shoes, ran north along the muddy cowpaths, and gasped when I emerged from the trees. Port Meadow was transformed to a shallow lake, the wide grasslands gone and instead—an expanse of blue water. Everything was blue and muted and pale. A smear of sun blurred the eggshell sky. Where were the cows? I wondered. Thousands of birds had taken over, fat seagulls mewing, ducks and geese and swans madly calling and honking as they claimed their new territory.

So the winter term began with wonder and continued to expand over the weeks. I found four kindred spirits and we formed a poetry group that met weekly in someone's room we brought drafts of poems, wine, and chocolate to share, laughing that we were the next generation of brilliant writers, and when they wrote our biographies they'd come sniffing around Oxford to reconstruct our rituals. These nights filled me with a sense of community, as well as a joyful faith in my own poems—and yet they couldn't assuage my solitary days. With no classes or seminars, only individual tutorials, my intellectual life at Oxford was entirely iso- lated, consisting of long hours in drafty libraries communing with books, shut up with my own ideas and fears. Sometimes I thought I couldn't bear it. I often went from breakfast to dinner without speaking more than a few words to anyone, and then woke to do it again.

But I began to take comfort in my loneliness. There was something historical in my solitude, something unexceptional and almost familiar, continuous with those who had stud- ied here before and those still to come. I became intimate with the architecture, the alleys and bridges. I watched the landscape and wrote its changes. I ran everywhere—through the parks, along the brown canal, past the houseboats whose names I knew well: "Reckless," "Queen of Hearts," "Miss Scarlett and the Rooster." The winter river moved slowly, the cold giving its surface a sheen like darkhoney, while underwater the strong currents roiled and swirled. I stood at the lock, the sluice-gates wide open, watching the water roar thick and grooved past the wood beams. By the time March brought the first rush of spring, warm breeze on my bare arms and the whole world dripping, I could lose track of time reading at my desk, a mug of hot tea be- side me and a red apple in my hand. Maybe it was only the weather after all, I wondered, adding "springtime" to my list of Good Things About England. Thick carpets of daffodils and blue scilla lined the pathways, and I felt such brightness in my heart that I didn't want to go to bed, wanting only to sit at the window and write, the air cool and sweet on my face.

There were long milky evenings, twilight until ten o'clock. The light dimmed and turned violet, a surreal cast on the world. One night I walked home from the library filled with vague nostalgia for the old damp streets, the earthy smells of stone and realized Oxford had somehow endeared itself to me, though I felt nothing close to passion, or love. On the corner of Ship Street a tall bearded man played the violin Vivaldi, "The Four Seasons" and as his thin body swayed, the music rose to the sky, drifted through the cobbled alleys, past the high Bodleian windows, whispered in the deaf ears of the stone emperors ringing the Sheldonian, and faded behind me like a dream.

Back with her family after completing her master's in English literature at Oxford, DIANA SABOT coaches novice rowing and cross-country skiing at Williams College.

My life felt delicate and impossible, as if it were landscape painting I kept wandering through, small

a story written for another character or a dark figure in the foreground,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

April 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureSpiked Boots and the End of an Era

April 1998 By Edie Clark -

Feature

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

April 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleThe Benefits of a College Town

April 1998 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

April 1998 By John MacManus -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

April 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRegional Leaders Named for Campaign

February 1958 -

Feature

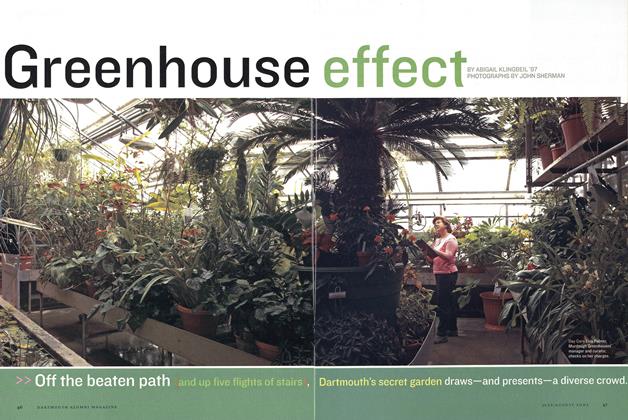

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July/August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

APRIL 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Feature

FeatureKnowing Squat About the Woods

MARCH 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO QUIT YOUR JOB AND HIT THE OPEN ROAD (IN A MOTOR HOME)

Sept/Oct 2001 By MARIANNE McCARROLL 84 -

Cover Story

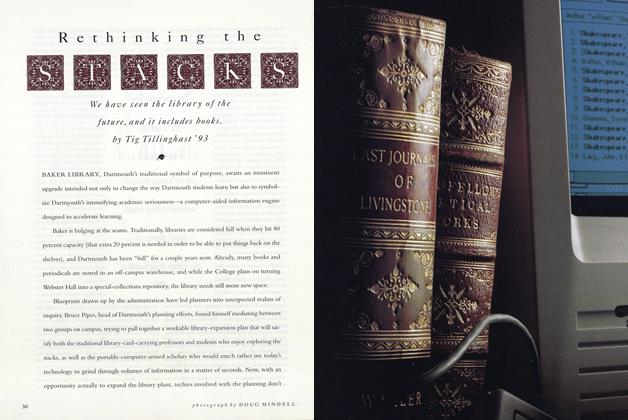

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93