Scientists must separate fact from fiction in the ethics of cloning.

HEADLINES announced that the study of life had reached yet another turning point: A novel scientific procedure had been invented, which some people feared gave mortals the power to play God. Researchers familiar with the technology cited its scientific and practical utility. Pundits, politicians, and even some scientists called for an immediate ban on its use. The year was 1973, and the first gene had just been cloned.

A year ago, headlines again announced a breakthrough in cloning: lan Wilmut, a developmental biologist at the Roslin Institute, near Edinburgh, had succeeded in creating a genetic duplicate of a six-year-old sheep. Using nuclear transplantation, a technique many had believed impossible, Wilmut had taken an unfertilized sheep's egg, surgically removed the nucleus, which contained the cell's genetic material, and combined the material with a cell he had cultured from the udder of a second adult sheep. A jolt of electricity caused the nucleus and cell to fuse and develop as an embryo, using the udder cell's DNA for instructions. The embryo was implanted in the uterus of a third sheep, which six months later gave birth to the second sheep's clone, named Dolly.

Some observers focused immediately on the possibility of cloning humans. Harold E. Varmus, director of the National Institutes of Health and a Nobel laureate in medicine, denounced human cloning as "repugnant" and "not consistent with traditional ideas about human individuality and diversity," although he later softened his position in testimony to Congress. Lan Wilmut himself, who appeared genuinely surprised by the media hoopla, said of human cloning: "All of us would find that offensive." Carl Feldbaum, president of the Biotechnology Industry Organization, urged that "human cloning be banned in the United States," as it has been in Australia, Britain, Denmark, Germany, and Spain. The Vatican, predictably, and the World Health Organization, unpredictably, also condemned human cloning, and on March 4, 1997, President Clinton announced an immediate ban, directing that "no federal money should be allocated for cloning human beings."

Clinton instructed his National Bioethics Advisory Commission to complete a review of cloning in three months, clearly too short a time for much reflective dialogue. On June 7 the commission recommended that cloning a human be made a criminal offense in the United States. Concluding that at present it would be "morally unacceptable" for anyone to attempt such cloning, the panel recommended that the government continue its ban on the use of federal funds to support research that could lead to cloning humans. (In late June leaders of the industrialized world, meeting at the Denver "Summit of the Eight," called for a worldwide ban on human cloning.)

In perhaps its most important recommendation, the bioethics commission suggested that any legislation banning human cloning should expire automatically after three to five years unless a body of experts, after careful consideration, decided that the law should be extended. The members of the commission intended this to convey their sense that they had not resolved all of the ethical issues related to human cloning, and that more extensive deliberation would be required.

I think we need to convene that body of experts now.

Daniel Dennett, a philosopher at Tufts University, once quipped that history doesn't repeat itself, but it sometimes rhymes. The two cloning breakthroughs—genes in 1973 and sheep in 1997 surely rhyme in this sense: In both cases researchers saw enormous benefit from the technology, while the public reacted with fear and loathing. But there is one important difference. In 1973 the scientists involved recognized the potential for harm and announced a selfimposed moratorium on further experiments, pending the results of a conference to discuss the issues in detail. The moratorium was remarkable, for even in 1973 the world of molecular biology was fiercely competitive, and scientists had never before voluntarily halted research.

But in 1997 it was the President who reacted first, not calling for a moratorium but rather imposing a ban. One might argue that the ban was really a pre-emptive ploy to defuse the concerns of the public and a conservative Congress, as well as a way of demonstrating that the Commander in Chief was in charge. Strategically, however, I believe that the Presidential ban was a mistake, for it implies that we already know that cloning people is evil.

The first cloning conference, held in 1975, was organized by scientists and featured international luminaries from science, law, public health, ethics, and religions, as well as representatives of the news media and the federal government. Its principal goal was to address public concern about the risks of cloning genes by making a series of recommendations to guide the conduct of future research which participants unanimously approved and sent to the National Institutes of Health. By 1976 the N.I.H. had issued its first set of guidelines governing research on recombinant DNA. Since then gene-cloning technology has become quite sophisticated; it is currently used on humans to treat such maladies as cystic fibrosis, elevated cholesterol, and AIDS.

Thus, the 1975 conference had much more than symbolic value. Initiating a pattern of reasoned discourse and education on the ethics of cloning genes, it allowed Americans gradually to accept the new technology. The Frankenstein scenarios that preoccupied early discussions gradually evaporated.

If scientists were to organize a new conference to discuss the cloning of humans, what questions should be addressed? The first, of course, is whether the technology used to clone Dolly is safe. As the bioethics commission concluded, the answer now is an unqualified No. It is not clear whether Dolly will age prematurely, be sterile, or suffer some malady produced by the procedure itself. Given the current lack of knowledge about how cloning works, the procedure is far too risky to try with people. It may turn out that fundamental biological barriers make it impossible to apply Wilmut's technique to human beings. Even to clone Dolly, the researchers fused 277 donor cells to eggs before they were able to produce a viable cloned animal.

A second question is: If human cloning becomes safe, would it be ethical? According to a report on National Public Radio, members of the President's bioethics commission were split on this issue. About a third believed that cloning people was unacceptable, a third had no ethical objections, and a third were undecided. It would not surprise me if rational and informed people continue to disagree about cloning, as they do about abortion. But we must address the concerns people have about cloning: including fears that clones would be used for spare body parts, the specter of "designer humans," and worries about the trauma of being an identical twin produced artificially rather than naturally.

If human cloning is eventually seen as safe and ethically allowable, a third question arises: Under what circumstances should the technique be used? The bioethics commission discussed the issues of infertility and reproductive rights, but the commissioners felt that cases of infertility were "insufficiently compelling" to justify cloning. It is not clear whether the commissioners foresaw other scenarios that would be sufficiently compelling, or if they believed that the clear potential for harm resulting from the misuse or abuse of cloning technology simply outweighed the great benefit that a few infertile individuals might receive.

If scientists do not initiate a detailed public discussion of the science as well as the ethics of cloning, we may find that only political and religious forces will determine the parameters of future research. That would be a loss for everyone.

Evolutionary biologist EDWARD BERGER hasbeen teaching students about genetics andbioethics since 1915. He is currents dean of thefaculty.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCall Back

May 1998 By Jay Parini -

Feature

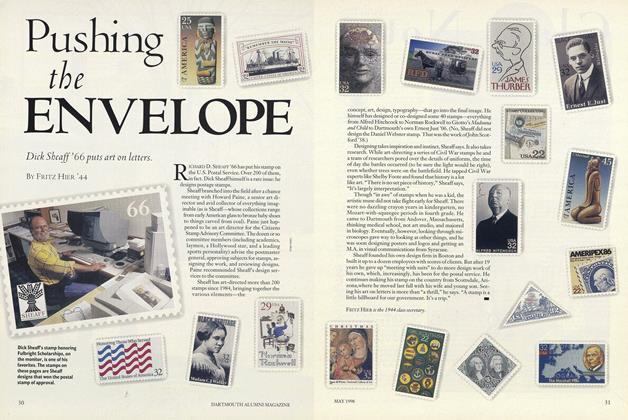

FeaturePushing the Envelope

May 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

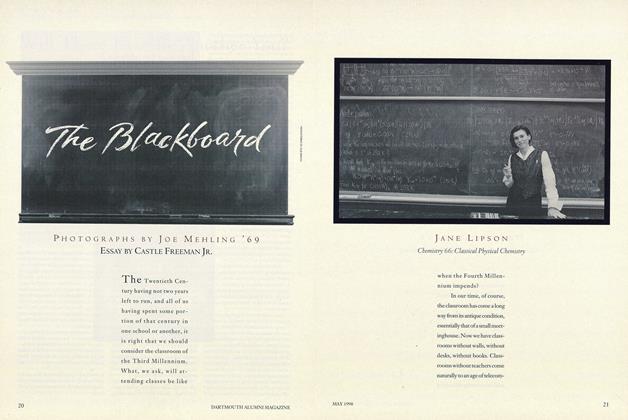

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Blackboard

May 1998 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Article

ArticleInfluential Minds

May 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1998 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, Jim "Wazoo" Wasz -

Article

ArticleOf Buses and Bells

May 1998 By Noel Perrin