Fifty years after he left Dartmouth as a freshman,Robert Frost returned to Hanover to teach "his hoys."

ROBERT FROST spent roughly three months as a student at Dartmouth in the autumn of 1892. He lived by himself on the third floor of Wentworth Hall facing away from the Green in a room that was heated by a coal stove. As he later recalled, "I let the ashes pile up on the floor until they reached the door." He was not happy there. As Thanksgiving recess drew to a close, and exams loomed in his various courses, Frost decided to abandon his studies. We go to college, he said, "to be given one more chance to learn to read in case we haven't learned in High School. Once we have learned to read, the rest can be trusted to add itself unto us."

Frost, though, never completely lost touch with Dartmouth. He went on to become a well-known poet, and came back to campus frequently to give readings and lectures. He liked to visit Hanover, where his daughter Irma lived with her husband, John Cone, and their two sons. Despite his abbreviated career as an undergraduate, Frost had kept an affection for the College "especially the students," said English professor Thomas Vance. "He was always warm toward them, called them 'my boys.'"

Frost formally returned to the fold in 1943. In March that year he was paid a visit from out of nowhere by Ray Nash, a lecturer in Dartmouth's art department. Nash was convinced that having Frost on the faculty was terribly important for Dartmouth, and President Hopkins agreed. At Nash's urging, Hopkins approached Frost with an offer to become Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities. "I am accepting your call back to Dartmouth with pride and satisfaction," Frost wrote in response to Hopkins's invitation. "Let's make it mean all we can. Call back, I call it. I once went to school at Dartmouth. As you know I am one of your alumni, though without benefit of graduation. I had my degree at your hands [an honorary Litt.D., 1933], I have been at Hanover many times to read in the last twenty-five years and the boys have given me some of my best occasions."

By Frost's third year as Ticknor Fellow, there was a new president at Dartmouth, John Sloan Dickey '29. Dickey wanted Frost to spend more time on campus. Frost decided to live in Hanover for several weeks at a time, in fall and spring. "He was not really teaching an academic course," Dickey recalled. "Frost was a presence, and important to us, and we hoped for more of him. He was amenable, top. Very quick to agree to whatever I proposed." Frost offered to grade the students, but Dickey explained that this was unnecessary, recalling a time when Frost had asked his students to write something for the next class: "He gathered the papers, and then asked the students if anyone felt strongly about anything in the work they had handed in. When nobody responded, he simply threw them all into the wastebasket, unread. It made quite an impression on them."

This sense of theatricality only added to Frost's popularity. The student body swelled with soldiers returning from the war, and many of them wanted to have the experience of encountering Frost. "Frost was popular with us," recalls Philip Booth '47, whose own poetry Frost came to admire. "He was keenly interested in all of us and wanted to hear about our experiences. He was especially interested in those of us who were married. I suspect he was attracted to young married couples—we may have reminded him of his own early days with Elinor." Frost eagerly sought out Booth and his young wife, and would often have dinner with them in their tiny apartment, talking happily until after midnight.

But Amherst College, ever since 1917, had been Frost's main academic affiliation. In 1948 it lured him back fall time. "Frost had a long-standing allegiance to Amherst," Dickey recalled. "It was the first college that had taken him in. I don't think any college before this had ever taken a poet on board—as a poet, to be a poet. Amherst had been remarkably far-sighted. We understood perfectly well that Frost had no choice now. He had to go back to Amherst."

That spring, Frost delivered his final lecture as Ticknor Fellow in the Great Issues course that was the brainchild of Dickey. "He was at his best that day," Dickey recalled. "He recited Shakespeare from memory the sonnets. He talked about the difference between science and the arts, favoring (of course) the latter. He mixed some politics into the talk always provocative, always thoughtful. The boys found him delightful, often very funny." English professor Harold Bond, a member of the audience that day, recalled "a peculiar combativeness, a defensiveness. Frost seemed to be laying down the gauntlet. But his timing was perfect. You had the sense of a mind whirling around a subject, coming at it from many angles. It was a singular mind. There was nothing like Frost in performance when it was going well."

Frost returned to Hanover in November of 1962 soon after the opening of Dartmouth's new Hopkins Center. Just a few months before the poet's death, in what would be his next-to-last public lecture, Frost spoke on the subject of "extravagance." He referred to the extravagance of the new building an elegant glass-and-concrete structure with tall windows overlooking the Green and went on to talk about the "extravagant universe." "And the most extravagant thing in it," he said, "as far as we know, is man the most wasteful, spending thing in it in all this luxuriance." He added that poetry itself was "a sort of extravagance, in many ways. It's something that people wonder about. What's the need of it? And the answer is, no need not particularly." He went on to read his poem, "Away!" In that autumnal poem, he said:

I leave behindGood friends in town.Let them get well-winedAnd go lie down.

Don't think I leaveFor the outer darkLike Adam, and EvePut out of the Park.

Forget the myth.There is no one IAm put out withOr put out by.

Unless I'm wrongI but obeyThe urge of a song:I'm bound away!

And I may returnIf dissatisfiedWith what I learnFrom having died.

Frost had by now acquired a benevolent, almost welcoming attitude toward death, keeping little in reserve; the threat to "return" if he found himself "dissatisfied." Buthe did not want to end his Dartmouth talk on that note. He concluded with"The Night Light," a little poem that had appeared in Steeple Bush (1947) as one of a group of poems entitled "Five Nocturnes."

She always had to burn a lightBeside her attic bed at night.It gave bad dreams and troubled sleep,But helped the Lord her soul to keep.Good gloom on her was thrown away.It is on me by night or day,Who have, as I foresee, aheadThe darkest of it still to dread.

"Suppose I end on that dark note," he told the overflow audience in the brand-new Spaulding Auditorium. Then he added emphatically, "Good night, good night to all of you." He walked off stage to a standing ovation.

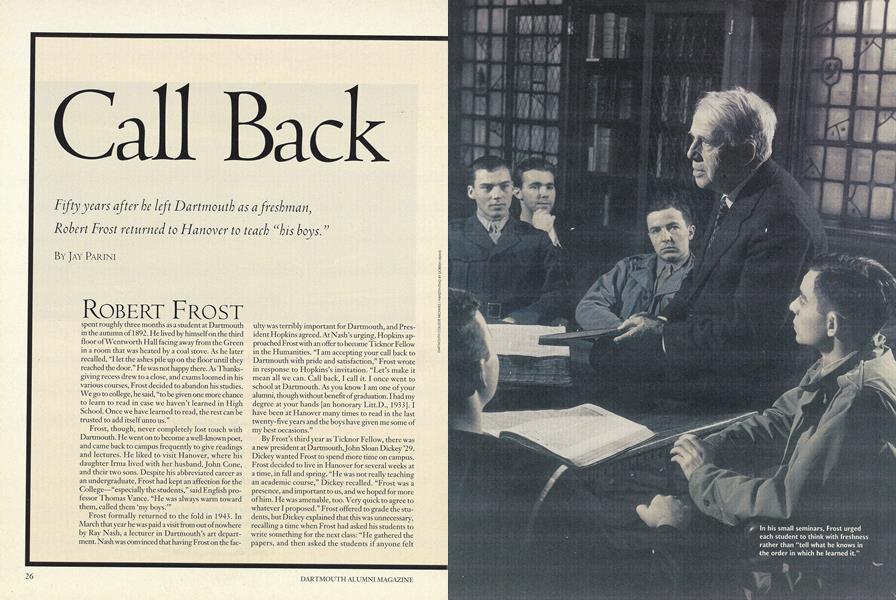

In his small seminars, Frost urged each student to think with freshness rather than "tell what he knows inthe order in which he learned it."

Frost embraced the Dartmouth ethos. His border collie, Gillie, accompanied him to class.

JAY PARINI is the author of numerous books of poetry, fiction, biography, and criticism. He taught at Dartmouthfrom 1975 until 1982, and is currently Axinn Professor ofEnglish at Middlebury College. This excerpt is adapted fromhis forthcoming biography, Robert Frost: A Poet's Life, to be published in the spring 0f 1999 by Henry Holt Co.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

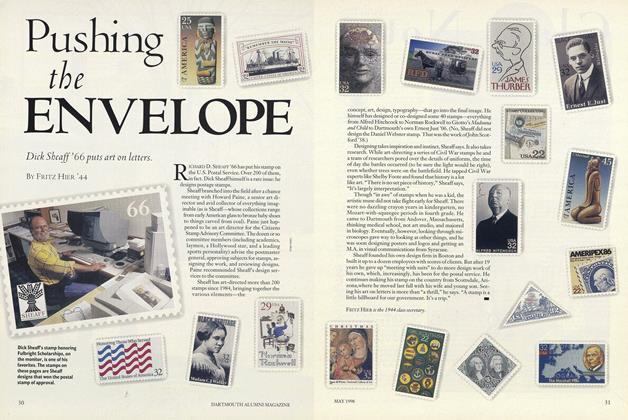

FeaturePushing the Envelope

May 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

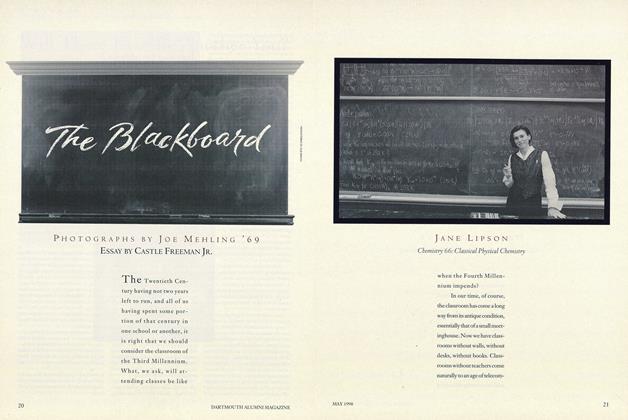

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Blackboard

May 1998 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Article

ArticleWill there Ever Be Another You?

May 1998 By Professor Edward Berger -

Article

ArticleInfluential Minds

May 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1998 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, Jim "Wazoo" Wasz -

Article

ArticleOf Buses and Bells

May 1998 By Noel Perrin

Jay Parini

-

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Jay Parini -

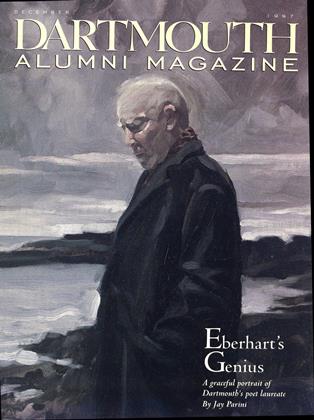

Front Cover

Front CoverFront Cover

DECEMBER 1997 By Jay Parini -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Full Mind of Richard Eberhart

DECEMBER 1997 By Jay Parini -

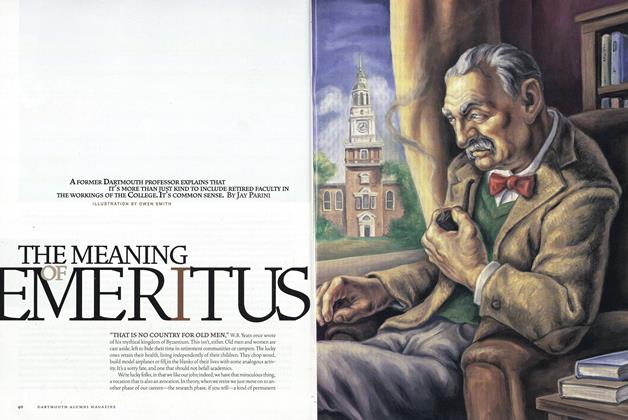

Feature

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July/August 2001 By Jay Parini -

Feature

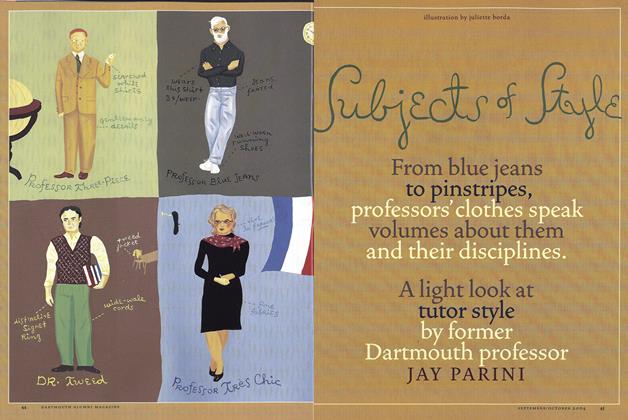

FeatureSubjects of Style

Sept/Oct 2004 By JAY PARINI

Features

-

Feature

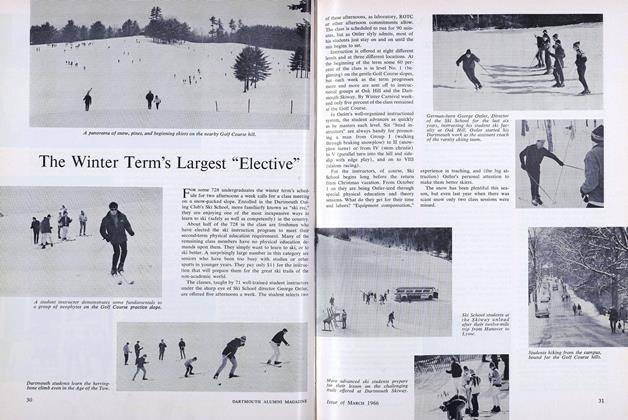

FeatureThe Winter Term's Largest "Elective"

MARCH 1966 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySartorial Splendor

April 1981 -

Feature

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureReflections

JULY 1966 By FLETCHER R. ANDREWS '16 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN CUSTOMERS WITH UNPRECEDENTED SERVICE

Jan/Feb 2009 By SCOTT MITCHELL '93