Intellectuals free us from the tyranny of short-sightedness.

I BEGIN WITH A PARADOX. Although Americans talk endlessly about the importance of higher education, in fact, we undervalue the role of intellectuals, including those who make higher education such a valuable resource for the nation.

I want to discuss four books published a half-century ago that reveal the power of intellectuals to open our minds to some of the most important issues facing society and deepen our understanding of them. The authors were intellectuals who grappled with contemporary reality, even as they stood back and viewed it from the broader perspective that a contemplative life provides.

The first is An American Dilemma, by Gunnar Myrdal, the Swedish economist whom the Carnegie Corp. ofNew York enlisted to direct "a comprehensive study of the Negro in the U.S." Published in 1944, this book changed our understanding of race relations and profoundly influenced the civil- rights revolution of the 1950s and 1960s; it remains the seminal treatise on issues of race in the United States.

Myrdal's analysis of economic inequality emphasized the nation's failure to include African Americans in the American Creed's promise of equal opportunity. Myrdal knew that it was impossible to transform 200 years of discrimination into genuine equal opportunity simply by proclamation, but he had confidence in the power of education and scholarship to produce beneficial changes.

A decade later Brown vs. Board of Education invoked Myrdal's book, An American Dilemma, as justification for its decision, illustrating the role of intellectuals in policy making. Myrdal believed that "there should be the possibility to build a nation and a world where people's great propensities for sympathy and cooperation would not be so thwarted." Myrdal's words warrant attention now, as this country is considering whether to diminish its commitment to the American Creed of equality by dismantling affirmative action.

A second influential book is The Affluent Society by john Kenneth Galbraith, pub- lished in 1958. Galbraith drew attention to the extensive poverty that persisted within our affluent society, even though it had virtually disappeared as a subject of public discussion. He defied the conventional wisdom of both liberals and conservatives by arguing that limitless growth and increasing productivity, rather than solving poverty and unemployment, had created new problems—such as inflation and the expansion of consumer debt that endangered the very economic stability that growth and productivity were supposed to secure.

Most of all, the "implacable tendency"' toward corporate growth and private profits threatened, Galbraith declared, to despoil the environment and impoverish public services by artificially generating even more consumer wants, thereby steering resources away from education, health care, social services, transportation, the urban infrastructure, and other important components of the quality of life. The central goal of the affluent society, Galbraith concluded, should be a "social balance" that secures "the minimum income essential for decency and comfort" and "education or, more broadly, investment in human as distinct from material capital." His book helped shape the public policy of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations to eradicate poverty in America.

My third book, The Uprooted, by Oscar Handlin, published in 1951, made an original contribution in conferring upon immigrants and the immigrant experience a prominent place in American history. "Once I thought to write a history of the immigrants in America," he began, "then I discovered that the immigrants were American history." Handlin depicted the psychological and social costs of immigration: alienation, depression, loneliness, loss of identity and status, poverty, prejudice, and strains on public resources. He also reminded us that each new generation of immigrants has typically been branded as worse and more problematic than earlier generations—slower to learn English, more insular in its consciousness of group identity, lazier or less ambitious, more likely to become public charges.

In recent years the political rhetoric concerning immigrants has again turned nativist and intolerant. Legislation reducing the eligibility of certain immigrants for welfare benefits has demonstrated an alarming measure of unfounded suspicion. As Handlin's book reminds us, ethnic and national diversity have been central to a cosmopolitan vision of our national identity, as well as a source of strength for our democracy.

My final exemplar is The Lonely Crowd by David Riesman, published in 1950 and perhaps the most searching exploration since de Tocqueville of the competing claims in America of self and society. Ries-man's title captured a disturbing paradox of modern American life. As the nation gradually evolved into a mass society dominated by large bureaucratic organizations, Americans increasingly felt isolated and alone in their atomistic individualism. The Lonely Crowd described the shift in American character from "inner-direction" to "other-direction." Selfreliant, inner-directed individuals, in Riesman's view, developed out of an emerging nineteenth-century capitalist economy. They were well suited to a competitive, entrepreneurial economy in which production was valued over consumption. As the United States changed from a production-oriented to a consumption-driven economy, the "other-directed" character emerged, more intent on impressing others than in leaving a distinctive mark on the world.

For all that has changed since the 1950s, we still face many of the troubling issues that Riesman addressed. We still are threatened by social and economic forces that erode the status of individuals from active citizens, working within a web of public and communal associations, to passive consumers, detached from one another and inundated by commercials, sitcoms, and headline news.

These four books, all widely read in their day, are now today more familiar and relevant than ever. They have changed our lives by influencing and shaping how we think about ourselves and our society. They are the works of intellectuals.

In a society excessively devoted to the bottom line—what the philosopher Williamjames called the "cash value" of ideas intellectuals free us from the tyranny of short-sightedness by enlarging our understanding of historical and sor cial context. They provide us with an alternative to a culture of celebrity and sound bites. We need, in short, to affirm that supporting the mission of intellectuals as critics, scholars, teachers, thinkers, and writers is one of the wisest investments society can make

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

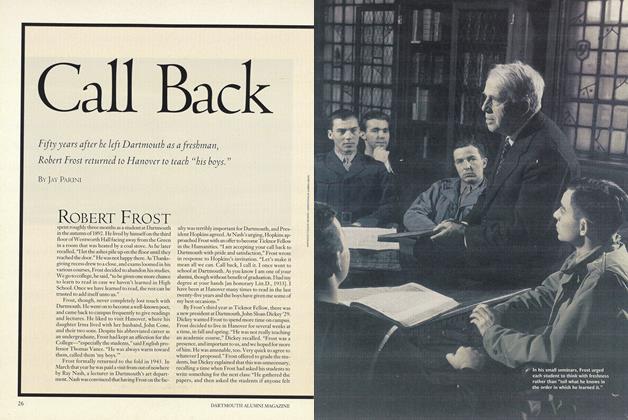

FeatureCall Back

May 1998 By Jay Parini -

Feature

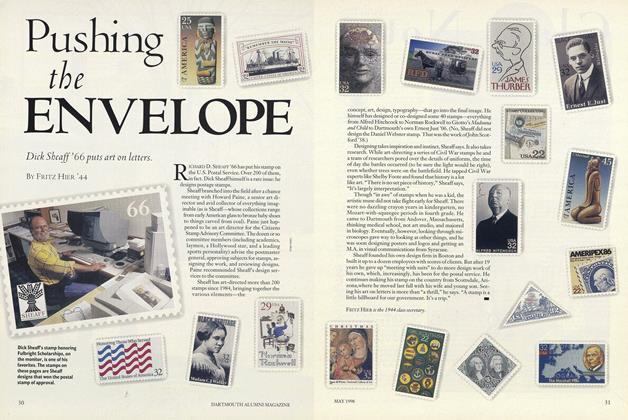

FeaturePushing the Envelope

May 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Cover Story

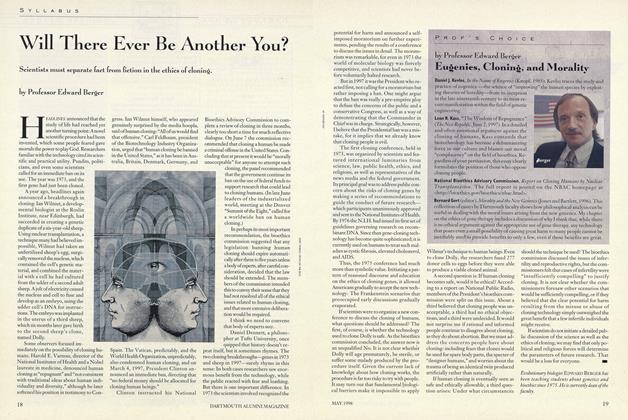

Cover StoryThe Blackboard

May 1998 By Castle Freeman Jr. -

Article

ArticleWill there Ever Be Another You?

May 1998 By Professor Edward Berger -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

May 1998 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, Jim "Wazoo" Wasz -

Article

ArticleOf Buses and Bells

May 1998 By Noel Perrin

James O. Freedman

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorPresents Accounted For

June 1994 -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Next Beginning

September 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Liberating Arts

MAY 1996 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleHockey

February, 1911 -

Article

ArticleALUMNI RETURN TO HANOVER FOR FEBRUARY 22

April, 1923 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

June 1952 -

Article

ArticleTHE HANOVER SCENE

October 1959 -

Article

ArticleModern politics "up close"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 -

Article

ArticleHAS NOTHING TO DO WITH ENTRANCE

AUGUST 1929 By E. Gordon Bill, Dean of Freshmen