Homer's hero described the good life for ancient Greece—and for us all.

The Iliad and the Odyssey have often been invoked as the Bibles of the pagan Greeks. If so, Odysseus of Homer's Odyssey speaks a gospel. For Odysseus related "the good news" that living an authentically good Greek life is an immediate and accessible reality.

Homer motivates Odysseus's gospel when the Phaeacian king Alcinous asks him, "Stranger, who are you?" Odysseus responds in Books 9-12 by telling stories of his journey from Troy; the legendary site of the Greeks' military triumph, to Ithaca, with its promise of a peaceful kingdom, close family, and loyal friends. But these stories reveal more than the single hero's quest. They are a kind of basic handbook of early Greek attitudes toward humans and their world.

Odysseus's adventures among the Lotus-Eaters, Cyclops, and Laestrygonians are presented as alternative modes of living. The Lotus-Eaters offer forgetfulness, a life of no concern or care but also of no achievement. The one-eyed Cyclops represents a world completely lacking in communal civilization. Men live separately, each in his own cave. There are no laws, no tribal customs, no meetings, no community farms. The Laestrygonians live together, have a king and a place of common meeting, but are monstrous butchers, destroying and drinking the blood of any stranger who comes near. By fleeing these societies Odysseus declares that each mode of living is inadequate for the individual who wishes to achieve a productive life in the company of others—an essential element of being a Greek.

Odysseus also learns from his other instructive adventures. An attack on the Cicones costs him crew members. He loses the Bag of Winds that could transport him home when his men give in to envy and greed. He withstands the seductions of Circe. In the underworld he learns the necessity of striving for a rewarding life while alive, for in death all opportunity for further rewards is gone. His encounters with the enchanting Sirens and his choice between navigating through the boat-crushing Clashing Rocks or facing the monsters Scylla and Charybdis illustrate the uncompromising threats of the world in which men must fashion their lives. The various landfalls represent stages in Odysseus's learning as he journeys physically and grows spiritually from the individualistic honor code of a warrior in Troy to the future cooperative society of Ithaca.

Each of Odysseus's adventures confronts long-standing tensions in Greek life. The first is between community and self-sufficiency. Aristotle said it plainly: "By nature man is a political animal." Greeks needed to live in a smallish community where they knew most other dwellers and meaning-fully participated with them in seeking to discover and work out the best possible life. This idea of the community-based life is so fundamental to the Greek way of thinking that Plato in his Republic found it the most effective model for a theoretical discussion of basic personal virtues—and each of these virtues, even when finally located in the individual, is designed to make the individual fit smoothly into a city structure. Thus Odysseus explores a series of varied societies and only then determines that his home community on Ithaca is the place where he can achieve the best life.

The second tension is between the heroic and self-destructive side of human nature. Odysseus runs into many beings who are marked by astounding insensitivity, and brutality. It is very Greek to find that humans are by their flawed nature condemned to a life which must consist largely of striving against their own self-destructive tendencies. Plato insists on the importance of education to reorient the soul from its commonly held "natural" condition. It is no wonder that Homer places such emphasis on Odysseus's learning to overcome an easy surrender to natural human weaknesses.

The third tension is between death and immortality. Odysseus learns that life is the place where humans must seek the only rewards which they will receive. He presents the afterlife as a helpless state in which the dead continually mull over their actions during life to see if they lived that life as fully and as satisfactorily as they could. It is a kind of perpetual No Exit, to use Sartre's term—a self-inflicted heaven or hell. Yet Greeks are always seeking immortality in some way. Achilles and Odysseus are immortalized by their appearance in epics; other Greeks are devoted to children who will carry on their names. Odysseus learns that death is a motivating force toward a fuller life—a life which, finally, immortalizes him.

The fourth tension is between chaos and order. The Greeks often saw the world as whimsical, dangerous, and chaotic and themselves as victims. Odysseus runs a gauntlet of destructive forces, an unordered series of life's threats and challenges. Yet even in such a world the Greeks tried to find order. Plato's vision of the harmony of the seven spheres provided a model of what the Greeks meant by an orderly universe. In addition to potential chaos in the material world, the gods who surrounded humans seemed constantly unpredictable. Later philosophers tried to distance the gods from human existence or else promote one god, Zeus, to such a level that he was an effective god of order. Yet polytheism always contained the potential for immense disorder. The epics and much of Greek tragedy show the difficulties for mortals when such gods powerfully interact with humans.

In each of these four Hellenic tensions underlying Odysseus's adventure tales, Odysseus chooses to pursue the aggressive end of the spectrum. He chooses to form his own community, even though he must work with flawed humans. He seeks immortality through poetry, in spite of having to fight for recognition in an undependable, even malignant, world. His choice is the best life available within Greek standards. And Homer shows that Odysseus—his Every Greek—has the opportunity to achieve the good life.

But who was it that Homer felt needed such instruction? All later audiences, including us. The Cyclops is not solely a lonely savage from a distant past; neither he nor the other characters met in the moonscape adventures are limited to ancient tales. All humans have moments when they would like to live alone with their own possessions, without the continual bother of a neighbor's intrusions, cares, and complaints-but if a person chooses to live on that level, he or she should know that the community will look a lot like him or her. The same is true of the concentrated brutality of "Laestryonianism" and the numbing apathy of "Lotus-Eaterism."

As Alcinous asked Odysseus, "Who are you?"

Odysseus navigated a tortuous journey toward the ideal life.

Classics professor WILLIAM SCOTT delivereda longer version of this essay as a Presidential Lecture for the campus community.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

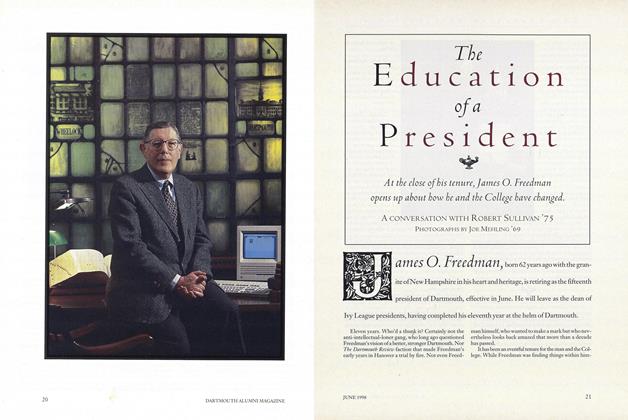

Cover StoryThe Education of a President

June 1998 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Comes NEXT

June 1998 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

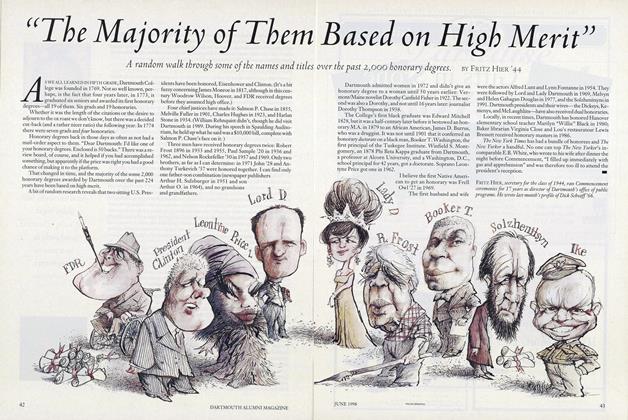

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

June 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleBack to the Future

June 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNewt ana Other Spring Speakers

June 1998 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

June 1998 By Don Casey Jr.