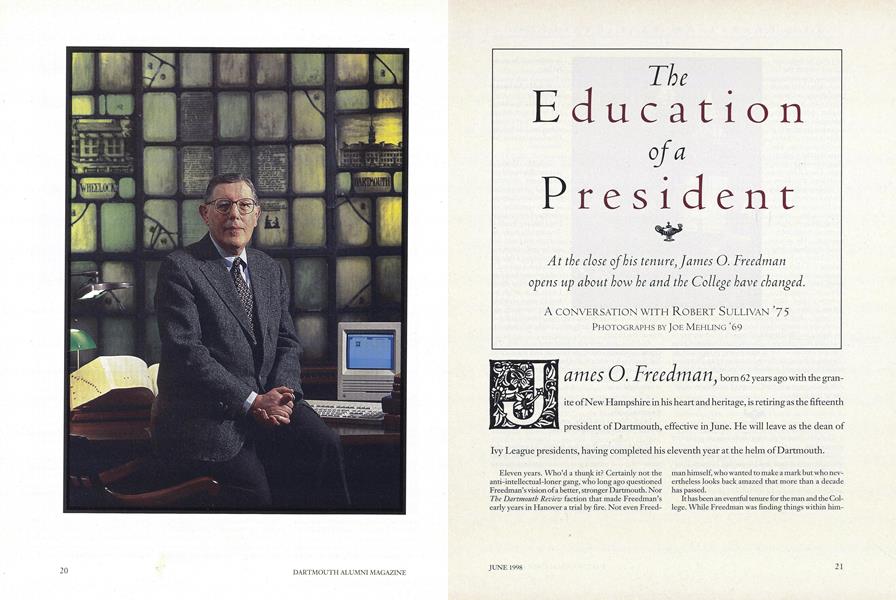

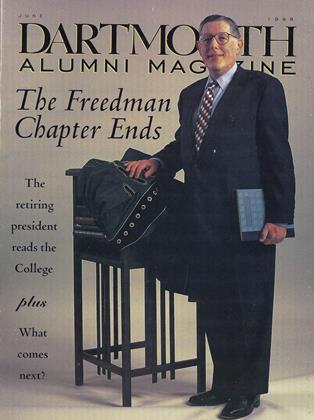

At the close of his tenure James O. Freedman opens up about bow he and the College have changed. A CONVERSATION WITH ROBERT SULLIVAN '75

James O. Freedman, born 62 years ago with the granite of New Hampshire in his heart and heritage, is retiring as the fifteenth president of Dartmouth, effective in June. He will leave as the dean of Ivy League presidents, having completed his eleventh year at the helm of Dartmouth.

Eleven years. Who'd a Thunk it? Certainly not the anti-intellectual-loner gang, who long ago questioned Freedman's vision of a better, stronger Dartmouth. Nor The Dartmouth Review faction that made Freedman's early years in Hanover a trial by fire. Not even Freedman himself, who wanted to make a mark but who nevertheless looks back amazed that more than a decade has passed.

It has been an eventful tenure for the man and the College. While Freedman was finding things within him-self self that he little suspected existed, the institution was standing ever-taller and more confidently as a major player in American higher education—finding things within itself that, perhaps, it hadn't been all that confident about. The man and the College sought terms of agreement, found them, and went forth to achieve.

Today, still on the job for a little while yet, Jim Freedman sits in his comfortable oiled-wood office in Parkhurst, surrounded by passions. He works amidst hundreds of the 6,000 books he has acquired ("There's no room at home anymore") and a collection of those...ummmm... colorful Toby jugs. These lively—not to say garish—British porcelains range from a scowling Beethoven to a particularly odd depiction of Rod Stewart during his "Rod the Mod" period. It is tempting to lead with that question—Does President Freedman knowwho Rod Stewart is? Or at least to ask, What's with theToby jugs? But since this celebration of an illustrious tenure is supposed to involve more high-minded inquiry—a give-and-take about the College during the Freedman years and the College of tomorrow—a different tack is set.

DAM.: First of all, congratulations on your years as president.

J.O.F.: Thank you. I would have been surprised had you told me back then that I would last 11 years. I'd already been president at Iowa for five years, and that's about the national average.

D.A.M.: Like an NFL linebacker. J.0.F.: Exactly! And I would have thought 16 years in total would be an awful lot.

D.A.M.: And was it an awful lot?

J.O.F.: Yes and no. It's been stimulating and gratifying right along, but I do feel like I've been at this for some time.

D.A.M.: When did you start thinking about retirement, and why?

J.O.F.: For the last year I've been thinking about it—once the ten-year mark was in sight. I had told the Board of Trustees I'd serve for eight to ten years, and the far end of that was approaching. I thought about how I wanted to reclaim some freedom. There are other things I want to do in life before it's done—reading, writing especially, and teaching. I'm going to take a year's sabbatical and then return as a member of the faculty. I definitely intend to stay on the faculty.

And then, also, this was a good time to do this. The capital campaign's done, the College is in good shape. You want to leave at a time when you can bequeath to your successor a healthy, strong institution. This is that time. Everything is blessedly strong and settled at Dartmouth right now.

D.A.M.: It hasn't always been thus, even during the Freedman years.

J.O.F.: No. As you know, my first two years at Dartmouth—we had some rocky times.

DAM.: Right off the bat, in fact. There was that immediate speculation—not only whispered, but in the press—that you weren't going to be here long because you were looking beyond this place.

J.O.F.: I was really peeved at that. Partly because you can't defend yourself. To issue a statement saying, "I am not looking to be president of some other institution" only confirms in people's minds that you probably are. So I felt really defenseless.

Also, one of the things I learned at Iowa is that you need a certain length of tenure in order to leave your mark. I don't know what the right number of years is, but I was sure that at a place like Dartmouth, one had to be here some significant period of years. So it never was a serious possibility that I would leave here for another presidency.

D.A.M.: Aside from those who were doing the whispering, how was your welcome to Hanover?

J.O.F.: Most people here were very warm and welcoming. On the other hand, I was surprised at all of the sniping on the grounds that I had gone to Harvard. I thought that was immature. I could see being teased about it, but I couldn't imagine that it would be serious.

The thing that took me most by surprise when I first arrived was the fierce loyalty of people to Dartmouth. Oh, boy, that is stunning. I'd never been at an institution where it was so—so—I don't know. It's intimidating when you're an outsider—such fierce loyalty really excludes those who aren't a part of the lodge.

Eleven years later, obviously, I'm very comfortable with that. But, boy, at the start it was quite a different phenomenon.

D.A.M.: Did you ever think: What have I gotten into? J.0.F.: Yes. You see, I was the first president since, I believe, 1828 not to either be a graduate or a member of the faculty when I was made president. And I think that Dartmouth at that time had a suspicion of outsiders.

In the talk that I gave the day I was introduced here, April 13, 1987,1 told the audience how I'd grown up in the shadow of this College, in Manchester, which was of course true. I thought I was playing the New Hampshire card. But it certainly had no resonance. I think it mattered to a few old-time, retired Trustees, many of whom used to be drawn from New Hampshire. But I don't think that it mattered a bit to the faculty or students.

It matters to me. It matters .to me a lot. I still meet people at Dartmouth and on the streets in New Hampshire who are now in their eighties, and who had my father in class at Central High School in 1943 or whatever. [Freedman's father taught English, his mother was an accountant.] It's really very, very touching.

Dartmouth loomed very large where I grew up. My high school always sent one or two students every year to Dartmouth. I remember that I saw the campus in high school when I was a debater and we came up here for a tournament. It looked gorgeous. I have a sense the tournament was in Webster Hall, but I'm not sure. I applied to Dartmouth, as you probably know. [He applied to Dartmouth, Harvard, and Yale.] I don't have a memory of what I thought at the time, of why I went to Harvard. Except that I knew a campus wasn't the basis for picking a college. That could be a bad view, but my parents had really made clear to me: It isn't the pretty buildings and it isn't the gorgeous lawns. That's not why you pick a place. My mother had always wanted me to go to Harvard. She thought that meant education.

D.A.M.: You went to Harvard, you tried Harvard Law, you worked in journalism, you went to Yale Law, you taught at Penn, you wound up at Iowa. What led you to take the Dartmouth job? J.O.F.: Two things. Obviously, the academic quality of Dartmouth. The U.S. News rankings then weren't as prominent as they've since become, but I had no doubt that Dartmouth was one of the top dozen schools in the country.

The second reason really was that the search committee had had long, soul-searching discussions of what Dartmouth needed, and they had a prescription: to make this a more intellectually serious institution with a greater emphasis upon its academic strengths, to develop its academic strengths, to do all those things that by themselves, when you saw them, would begin to counteract the concern about an Animal House image. That concern was certainly very real at that time.

It was a search that really said, "We're looking for intellectual leadership on the academic side to make this place stronger." Dartmouth at that time was, obviously, a first-rate institution, but it had an opportunity to get better. They appreciated that this was a moment and an opportunity to get better. They were serious about it, and that was what was most attractive.

Coming back to New Hampshire was very attractive, too.

D.A.M.: As you retire, the prescription they laid out is very much how your tenure will be defined. J.O.F.: Yes.

D.A.M.: But in the first two or three years, there were a lot of headlines about other matters.

J.O.F.: Yes, there were.

D.A.M.: The Review

J.0.F.: Yes. The speech I gave to the faculty on The DartmouthReview was, I think, on March 28,1988. Then the second business with The Review, the big rally on the Green, was in 1990.

The issue was just unavoidable. I knew hardly anything about this beforehand. A little piece in The NewYork, Times about the shanty incident, maybe. But if there was more, I didn't see it as very big.

When it came up during the interviews, I took the stand that you cannot touch The Dartmouth Review. Free speech needed to be tolerated, and I've always believed that.

When I got here, I was surprised to learn what a large, large cloud this was over the campus. And it became clear to me that the faculty and others were just waiting to see how I would be tested when an incident came up. I thought we would just have guerrilla warfare where they would print outrageous stuff and I would say, "Our job as an institution is to answer back."

What happened that first year was the incident with Bill Cole [an altercation between the music professor and Review staffers, which led to a student's suspension and a lawsuit which was later thrown out of court], I was on the spot, it was my obligation to speak on it. Which I did.

I, obviously, did not know when I gave that speech what the outcome would be.

D.A.M.: Were you gratified by the response?

J.0.F.: I was enormously gratified. It was the most touching moment in the world when the faculty gave me a standing ovation.

D.A.M.: What about the reaction you got from alumni?

J.0.F.: Enormously mixed. There were people who wrote and said, "finally and thank goodness." And then there were all those who felt the other way.

DAM.: That wasn't the end of it.

J.O.F.: No. We had the second incident, with that huge rally on the Green. This one, of course, was about being Jewish. By this time they had portrayed me in a Hitler outfit. They had written that I was out to have a Final Solution and a holocaust and the like. I mean, that was really, really personal, ugly stuff.

I was humiliated that Dartmouth was being portrayed as having an anti-Semitic element in it. That would be humiliating whether the president were or were not Jewish. Here, too, it seemed to me that I had an obligation to speak.

D. A.M.: Did your reaction to this personal attack—your decision to get into the fight— surprise you? J.O.F.: It did.

D.A.M.: Contrary to your nature ?

J.O.F.: That's right. I am not, by nature, a confrontational person. I'm much more a conciliatory person, a mediator, a person who tries to find a soft approach rather than a blunt approach. It did surprise me. But there just was no other way.

D .A.M.: That was a turning point. Your speech on the Green seemed to doom The Review. It seems like they just fell off the cliff after that.

J.O.F.: Yes. No one sees it at all anymore. But, you know, it has always been written by 20-year-olds for 60-year-olds off-campus. Its audience is and was people who, like Miniver Cheevey, curse the day they were born and wish the place were different.

D.A.M.: And The Review's issues—the Indian symbol, coeducation, the College song—have they all gone away as controversies now?

J.O.F.: The Indian symbol's completely gone away. The Alma Mater controversy has, of course, gone away. Coeducation has gone away as a controversy.

Part of that is, interestingly, that the median class now for alumni is the class of 1974. So half of our alumni have graduated while this place was coeducational. We've graduated 11,000 students since I've been here—out of 50,000 total alumni. The place has changed, yes. The alumni, too, have changed.

D.A.M.: How about the students? Do the kids here, walking across the Green on a given day in 1997, resemble the kids who were here in 1987?

J.O.F.: I don't see them as different. Their scores are different, their paper records are different, but I don't see them as different. The artifacts of the time—the way people wear their hair or the way people dress—change. But I see the kids as bright and ambitious.

D.A.M.: Are they politically involved?

J.O.F.: Not a great deal, no. The '96 campaign was a mere blip on this campus. The '92 campaign, there was activity here, but that was primarily because Paul Tsongas was running and Tsongas was, of course, an alumnus and an interesting figure.

D.A.M.: What accounts for the diminishment of activism on campus, and is it a cause for concern?

J.0.F.: I think it is a cause for concern, and I think it reflects the nation. I am a strong believer that what kids bring to this or any other campus comes primarily from their home and their peers, and that what kids bring at age 18 is awfully hard to change—except the intellectual part. Other parts are hard to change because parents are powerful people in our lives, and I think that kids come here from homes that reflect what's going on in the nation. And that is: Politics do not seem very important. The enthusiasm about candidates has not been high.

D.A.M.: Is it that there's a career orientation among freshman? Do they arrive knowing that their parents expect them to major in a subject that puts them on a professional pathway through life?

J.O.F.: I don't believe that the reason students are not giving time to politics is that they're so absorbed in careerism. They are giving extra, non-career-oriented time to all kinds of things, from playing pinball machines to touch football to Frisbee. They've got time. It really is that politics don't engage their interests.

Now, separately, I do think there's more careerism than there used to be, and that's both a healthy thing and not a healthy thing. I think that the very high cost of college has led many, many families to say to kids: These are not four years to figure out who you are, and to make a lot of false starts. This is serious business at $30,000 a year, and you really better keep your eyes on the prize.

D.A.M.: How is that good and how is that bad?

J.O.F.: The good part is that it really makes this a more serious enterprise. The bad part is that it intimidates some students from engaging in trial-and-error exploration of who they are and what they might become. It would be much better if there were a more relaxed attitude about that.

It's funny, I have had office hours every Monday afternoon, one-thirty to three, and students come in. One of the things that's grown over these 11 years is the number of students who tell me that their parents expect them to major in a science and go to medical school, or economics and go into business. But, they tell me, they've fallen in love with Portuguese literature and they'd like to major in that, or they've fallen in love with the German language and...

D.A.M.: ...and could you call my parents?

J.O.F.: [laughs].. .and how their parents just won't go for it, simply won't accept it. They feel they can't explain it to them because there's a gap of generations and experience. Some of them tell me, "So what I'm doing is, I'm majoring in Spanish and biochemistry." Or, "I've got a double major—economics and French history. " More of them just tell me they're trying to cope with this parental pressure. They want to please their parents. We all want to do that. But it's hard.

When parents are here on parents' weekend, I hear almost nothing face-to-face. What I do get is letters from parents about how very expensive this is, and some of these are very poignant stories. People do feel they're being asked for more than they think they ought to be asked to give.

There's a sense that it's getting to a point in this nation where we're not going to pay much more for education. Last year Congress appointed a commission to assess the national environment on this. I think the attitude now is: This has gone too high, and increases must be very small.

It's something worth looking at, because the cost of higher education can change higher education. We can become merely a symbol, an elitist item. College has become, next to a house, the biggest item that any family purchases. It's obviously four or five times more expensive than a car. And while some Americans want to make sure it represents value for all this money, others would be willing to pay almost anything for it.

America has become so affluent that all the other symbols of elite achievement and status are now widely shared. The fancy neighborhood, the big title, the Caribbean vacation, the Lexus automobile. The last status symbol left is to send your child to an Ivy League school. And for some parents, not just any old Ivy League school, but a certain Ivy League school, or a certain few Ivy League schools. And that has increased a sense of urgency—that it's socially necessary.

D.A.M.: But it's an item they can't control. They can't just buy it.

J.O.F.: Right. It has become the last symbol that's still out there and that is scarce. You can always get a Lexus, but you can't always get this. So a school could just keep charging more and become a rich, elite club. You could do that, and people would buy in. But we haven't done that; we've tried to contain costs.

At Dartmouth our primary goal is to provide access to all kinds of talented students, regardless of their financial situation, and that means we must remain need-blind. Our campaign was a big plus, in that we raised $54 million for scholarship endowment, which at five percent income a year is about $2.5 million toward new financial-aid resources.

The other thing you could do is cut costs. Seventy-five percent of the budget of Arts and Sciences is staff and faculty salaries and professional salaries—in the library, in computing, nurses, counselors. But, gosh, you don't want to cut back on those, because you'll lose the very best people you have.

Or you could raise prices for lots of things that students pay for out of pocket, like tickets to the Hop. You could raise prices for going to Berry Gym, for use of the weight rooms and swimming. But those are nickel-and-dime things, and it's not what you want to do, either.

D.A.M.: So in all, do you see a threat to Dartmouth's need-blind status?

J.O.F.: There is no imminent threat. To give an example: With Princeton, 95 percent of its financial aid is endowed. Our capital campaign helped us greatly. We were at 28 .percent when the campaign started. We're now4B to 50 percent endowed, and that's good news. We believe there are no more than 12 schools left that are need-blind, and some people think it's only eight. There are two Ivies—Brown and Columbia—that are not need-blind 100 percent.

D.A.M.: Who is our competition now, and has that changed in ten years?

J.O.F.: When I came, there were five schools that, when we admitted a person and the other school did as well, 85 percent of the students went there. They were Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. As I'm leaving, we still lose 75 percent or more to Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Stanford. We've made a marginal increase. We break even or usually lead by a sliver with Duke and Brown.

D.A.M.: At the end of the Freedman tenure, are we hot? There was an article in The New York Times calling Dartmouth "a hot school."

J.O.F.: When the woman wrote that article, her editor questioned her on that and said, "I need the proof. We can't call it a hot school if we don't have the proof." She did some work, and The Times printed it.

I think it's that, in a four- or five-year period, we had a 40 percent increase in applications. And if you look at scores, which is one of the ways in which we assess student quality, we have closed the gap greatly with the top three Ivies-Harvard, Yale, Princeton. We're just a sliver behind the number three school, whereas when I came we were nowhere near as close to the top three. High school counselors know that. I think part of what makes you a hot school is who the juniors look up to from last year's senior class. Who went where last year. And when a few more of the best kids in every class go to Dartmouth, Dartmouth gets hot.

D.A.M.: Do some of the old verities still apply, outside of the intellectual? For instance, did we see a spike in 1997 when the football team went 100? When I was in high school in 1970, 10-0 put Dartmouth on my radar screen.

J.O.F.: That doesn't apply anymore at all. Football doesn't do it. I think it's possible that women's sports could do it—a woman's soccer or lacrosse team that does really well would get more attention in high schools these days than men's football. Why? Because those are nationally ranked teams, and that can make a difference in high schools. We often have a woman or two in cross-country who's in the top half-dozen in the country.

D.A.M.: So these bright young people—brighter than yesterday—get here. What curriculum greets them? Where does Dartmouth stand now, vis-a-vis the national debate on curricula?

J.O.F.: I'd be surprised if anyone could look at us fairly and not think we were middle-of-the-road. The new curriculum is more prescriptive than the prior one. There are more requirements in it. Students have less freedom within it than they had before. That has got to put us somewhere in the middle of the road.

Dartmouth now requires a culminating experience, so that you can't just take eight courses in history. You have to take a ninth that's about the meaning of history or the nature of history, or something that tries to tie it all together.

I think we're much more disciplined in what we ask of students now than we used to be, and more so than many other places are.

D.A.M.: Is there anyone out there these days doing one of those radical Hampshire College things? Or is that, with a $30,000 price tag, impossible these days?

J.O.F.: There are places doing that. I think some of these have been very successful in appealing to a certain kind of student. Hampshire has a group of graduates, like [the documentary filmmaker] Ken Burns, who attest to the fact that this is an awfully good way for some people to come to maturity. I admire David Mamet, who went to Goddard College, which is a similar kind of place right across the way here. For some students, those are, obviously, very nurturing places.

D.A.M.: And at the other end of the spectrum, what's your take on Allan Bloom, and the return-to-Western-civ movement?

J.O.F.: My take is that Allan Bloom is really looking back to a golden age where once upon a time everything was wonderful. I just don't know if there was a day when students spent their four years absorbing Plato and Nietzsche. And I can hardly get as excited as he gets about rock music and its debilitating effect on the soul.

My own sense is that all adults would love students to be more serious than they are, and it takes a little bit of time to appreciate they are still 17 years old when they come here, maybe 18. They are still young.

DAM.: Where does the College stand as regards political correctness? Are we perceived as a politically correct place, or perhaps a too politically correct place, in areas of curricula and free speech and so forth?

J.O.F.: I think that is a label whose time has passed. I think it served some rhetorical purposes, but I've never thought Dartmouth was politically correct, and I don't think that students for one minute would permit this to go on in the classroom. Students are the most skeptical, honest people there are, and I don't think you can, in the classroom, try to hew to any kind of political line without exploring all the deficiencies and vulnerabilities it may have.

D.A.M.: But it's the students who are sometimes accused of it—agitating for women's studies or Holocaust studies, to take two things that have recently sparked controversies on other campuses.

J.O.F.: The primary impetus for specialized studies differs. I think with women's studies, which was well underway before I got here, the impetus was from women faculty who were interested in these issues, who came of age at the time when all that was occurring.

Here, now, the impetus for Latin-American studies, Caribbean studies, Asian-American studies, is coming from students. Students are talking about the Asian-American experience in America—what their parents and grandparents went through; what their heritage is, and what it means, today, in this country, to be an Asian-American. From such discussions, faculty members will propose to the committee on instruction, which is a faculty committee, that they would like to give a course or several courses in a new area. They submit a syllabus. They appear in person and discuss it with the committee, and the committee will either approve or disapprove. When it approves, it typically does so for a short period—a year, two years, three years—and expects to review at the end of that period. This is how something moves toward being a program, which is a step below a department, and then it may become a department. And that may take ten or 15 years to occur. But there are checks along the way. It's really the faculty that controls the curriculum.

D.A.M.: Speaking of faculty: The undergraduate teaching is at a very high level?

J.O.F.: Very much so, very high. I think it would be hard to be a faculty member here and not be a good teacher. I don't say spectacular, but more than just ordinary, because this is a savage place on people who are not good teachers. Students are savage, and faculty peers can be. It's a place that prides itself on teaching, and the good teachers want that reputation upheld.

There are evaluations now in virtually every class. It's just hard to be a faculty member with your colleagues if you're not a good teacher. With the students, they know, and they let you know, if you're not up to snuff. This is a very consumer-driven culture in terms of teaching.

D.A.M.: Now, what about the amount of teaching? The load for the faculty, which you are about to join, is a course lighter?

J.O.F.: Lighter than 15 years ago. The process started in the middle eighties of moving to a four-course teaching load. It used to be higher.

D.A.M.: What does that do to the classroom experience, if anything?

J.O.F.: I don't know that it does anything adverse to the classroom experience of students. It obviously gives faculty more free time than they had before. How they use that time, whether they use it for scholarship or for teaching or for other activities—service on committees and governing the College—is obviously their choice. The goal was to give faculty more opportunity for research, more opportunity to prepare classes, more opportunity to do service to the College.

D.A.M.: Is such a change effected with an eye toward being able to compete for the best faculty with other schools, or is it done in order to get the fruits of the research?

J.O.F.: It's done after detailed analyses of teaching loads at the 15 or 20 schools that we most compete with for faculty members, because it's just clear as can be that when you're competing for faculty, or when you're trying to hold a faculty member against an offer he's gotten elsewhere, then teaching loads are one part of the coinage, part of the currency.

D.A.M.: Is there going to be an increase in class size or will we need to add teaching assistants as a by-product?

J.O.F.: No. This has really been incorporated into the place by now. We now have 340 faculty in Arts and Sciences, and when I came we probably were at 320. The capital campaign has allowed us to create new chairs and add new people, and the student body has not changed in size. So the faculty-student ratio is probably a tad better today than it was ten years ago.

D.A.M.: The fact that U.S. News & World Report ranked our undergraduate teaching number one is something we're happy to let others know, I presume. J.O.F.: Right.

D.A.M.: But the follow-up is: What has U.S. News& World Report and the spreading attention given to rankings done to American higher education in the last ten years?

J.O.F.: All of us sit here and tend to say it's done very bad things. But I would say it's done good things and it's done bad things. What I don't like is that it has implied a precision which does not exist in terms of how you rank places. It has created campaigns by institutions to get votes to move them higher. I get letters from schools that are highly ranked, schools that are in the second tier and the third tier. They say, "I just thought you'd be interested in all the wonderful things we are doing today at the University of Whatever. We have a small student-faculty ratio, we do this, we have a new program in that, we emphasize this...." You get these PR things, and some say very candidly, "This is the time of year that we're all asked to vote, and I myself am frustrated because I'm asked to vote on schools I really don't know much about, so I just want to be sure that you know enough about South Dakota Southern." There is now this campaigning for where you stand, and that's bad. President Casper [of Stanford] led a campaign, and wrote a very famous underground letter urging U.S. News to get out of the business.

D.A.M.: Are we going to join any effort against the business?

J.O.F.: We are not. I think Dartmouth is more or less fairly treated. I think if anything we have benefited by getting publicity in parts of the country where we're not as well known as the schools we're grouped with. I think it's fair to say that on the West Coast, people who know Harvard, Yale, and Princeton may not know Dartmouth. By being reminded by U.S. News that we are in that same league, I think that probably helps us.

And when I said the rankings have done some good, I think a part of the good is they've helped to identify any number of schools. Tufts is just thrilled to be 22nd—they've made it into the Top 25. Their applications have shot up as a result.

D.A.M.: This would probably be something a college wouldn't like to admit, but is there any strong reaction, internally and otherwise, to low numbers received in the 15 or 20 categories assessed by U.S. News?

J.O.K: Yes, there certainly is. For instance, one of the things that is measured is "yield"— what percent of students that you admit choose your school. If you admit 100, do you get 85, or do you get 55? Now, in early-decision acceptances, every student you admit must come to you. Well, in the last two years the number of students admitted early-decision has gone way up. Some people think this is in order to increase your yield, because you get 100 percent of those early admissions. If you can take 40 percent of your class early-decision, that's going to make your yield much higher, and you look tougher and better.

D .A.M.: Early admissions have gone up at a whole bunch of schools?

J.0.F.: Yes, all over the Ivies, and all over everywhere else. Harvard took more than 50 percent of its class. They don't have to worry about yield, they have the highest in the country, but they took more than 50 percent of their class early-admission last fall. We took the highest percentage I think we've ever taken, 30-something percent.

And there are other things that schools are doing to try to manipulate the rankings. First of all, everyone in the last ten years, including me, has been going to Washington to see the rankings issue editor at U.S. News. Last time I had lunch with him, he said, "Oh, President Shapiro of Princeton took me to lunch last Tuesday. President Gregorian at Brown was here the day before yesterday." We all court him.

Dartmouth's plea was that they add a category for alumni giving, because that proves loyalty and shows something about the alumni's feeling about the place—and this must be a reflection of quality. That's not so logical maybe, but every school has a statistic it would do well on, and that it tries to persuade U.S. News to incorporate.

D.A.M.: Did we get that category in? J.O.F.: Yeah.

D.A.M.: Dartmouth does very well in the assessment of how well the current student body likes its institution—tops in the country, I believe. But is there anybody here—to go back to your famous comment of 11 years ago about making the intellectual loner feel welcome in Hanover—is there anyone who might not feel welcome here now?

J.O.F.: There are students who don't feel comfortable. I think there are on any campus, and I think that there are people who, for some reason, might not find this the right place. The same way some people aren't comfortable in New York City and some people aren't comfortable in Randolph, Vermont, there are some people who are not comfortable at any particular campus.

A group that might find it hard to feel comfortable here is minority students. We still have a very small minority community, though next year it will be the highest it's been in many years—more than 25 percent. That's smaller than any other Ivy League school. There's not a surrounding minority community in the area, there's not a black community, there are no black churches. When you only have seven or eight percent black students, which is all we have, that's 70 students in a class of 1,050. That's not a big number within which to find people who come from your background and share your concerns.

A tangent to this minority question is an ugly national mood, which has suggested to a lot of these kids that affirmative action is bad and wrong and you probably ably don't belong there and you got in by a special break and you don't deserve your place in the class. All that national ugliness—it plays in these kids' heads.

D.A.M.: What's the future of affirmative action? What will be done at schools such as the University of California and the University of Texas, which have seen a voter initiative and a recent decision change their affirmative-action programs? Are they going to throw in the towel? Is there any ambivalence about the decisions?

J.O.F.: I don't think schools are at all ambivalent. I don't think Berkeley is ambivalent. I think Berkeley's furious about where it was put, and I think Texas is furious at the position it was put in.

It's possible that affirmative action in its present form will be modified or won't quite survive, but I think that some program that makes sure we are educating minorities is absolutely essential. I think it ought to be permissible to take race into account as one of a multitude of factors in making a decision, because one of the purposes these institutions serve is to educate men and women to be leaders of society—and minorities have to be among those leaders. I can't imagine the state of Texas without a substantial number of minority lawyers, black lawyers, coming out of the leading law school in Texas. And that's apparently going to be the case, until we find the next solution.

I'm not enormously optimistic. I'm not optimistic about the future of affirmative action, in the sense of what our courts will do.

D.A.M.: And for others besides minorities—is Dartmouth now a comfortable place?

J.O.F.: For most of them, clearly, For some others, I think that there still aren't places here to find solace. When I went to Harvard, you could go to the movies every night of the week if you were really depressed and felt out of it. Between Boston and the university, you had a big choice. You could go see the Red Sox every day from April till June. You could do a lot of things that just took you out of the community.

You can't do that here. It's much harder to get out of this place, because there isn't anyplace to get out to.

D.A.M.: Maybe cyberspace. This may seem like a five-year-old question, but is technology still changing the nature of a Dartmouth education these days?

J.O.F.: I think so. But my sense is that technology has not changed higher education in anywhere near the degree people have predicted it would. There was a period where people said television was just going to change everything. I don't think that's happened. There was a period when people said computers were going to change everything in education. I think computers have been very helpful with programs that help students do rote kinds of things—learn languages, for instance. They offer opportunities for modeling processes or doing simulations in any number of areas of study. But they don't replace the professors. They can—and do—augment the professors, but they can't really replace them.

Technology has been most influential in research. The amount of information that's now available on the Internet is really incredible. The NewYork Times now has on the Internet 40 years worth of book reviews. So if you want to see the daily book review when The Catcher in the Rye came out, or when Invisible Alan came out, or when TheFeminine Mystique came out, you can see the book review. That's amazing.

D.A.M.: But we're building a bigger library.

J.O.F.: Well, Baker was built in 1928. That's 70 years ago. Baker is absolutely crammed. I mean, there is not room for another book in Baker. Baker was also built when the student body was half the size of this student body. So you have twice as many students 70 years later trying to use that library. And Baker was built before the computer age, so everything in Baker is awkward and clumsy. You can't wire effectively in Baker because the walls are so thick. We've done it, but in the most cumbersome, elephantine way.

We simply need more space for books and we need more space for computer equipment and technology.

D.A.M.: Do you anticipate a growing student body? J.O.F.: The Board of Trustees has made clear that the upper limit on undergraduate students is 4,300. We've never been that high. We are at 1,050 to 1,080 a class, and that's roughly 4,200 each year. It's not going to grow.

We're certainly going to grow in facilities. We're putting up a new library, we're putting up a new psychology building, we will in the next five years build a new math building. In the next ten years, a new biology building. There certainly will be new residence halls within the next several years.

D.A.M.: You spoke of some disadvantages of being up here in the Upper Valley, but in our modern age aren't there advantages too? In attracting faculty? In quality of life for students? This is a setting that seems, as others are developed and over-developed, increasingly beautiful.

J.O.F.: That's right. I think those are pluses—the attractiveness is one, the environment. This is a generation of kids that grew up caring about the environment and the outdoors and we are, obviously, an exemplary place in that regard.

A second thing is scale. We have a relatively small, human scale. The instructions given to our campus planners are that everything should be a five-minute walk from Baker. From Baker to Berry or the football field, maybe it's ten—but we're still close to having a very nice scale.

A third thing is safety. We do not have the problems that Penn or Yale or Columbia have by being in an urban environment and, in some instances, a very dangerous urban environment. When I occasionally talk about this subject with colleagues elsewhere, they say that they get mail from parents who believe that the school is not taking enough effort to protect their kids against physical harm. If you go to Harvard or Yale after a certain hour at night, you can't get into the yard or the central areas. You need a key to get into every single dormitory. Here you can walk off the street and go into Baker, go anywhere you want.

D.A.M.: If we could turn for a moment to the personal: How did your bout with cancer affect you personally? It was a time of great reflection, but how did that episode interrupt your tenure here? And when you came back to the job, did you look at it any differently? Had you changed?

J.O.F.: It clearly changed me. First of all, cancer slows you down from a trajectory that you've been on since you were 17 years old. You always felt you had a sense of destiny, you were destined for significant things—and if you worked hard enough and maybe had good luck, you'd achieve the things you want. Suddenly, when you get cancer, you see that you are very vulnerable, and that this sense of destiny has maybe played itself out. It's not ordained that everything is just going to be in this upward path of more and more satisfactions. It forces a real sense of vulnerability on you.

It changes your relationship with your spouse and children, bringing you much, much closer. There's suddenly this recognition that we're all not going to be here forever, and you value each other more.

It changes the way the world looks at you because the world no longer looks at you as invincible, as this person whose career was on an upward climb. The world suddenly begins to look at you and think: I wonder if he'll be here a year from today? I wonder if he'll be here two years from today? It changes the way the world commits itself to you. It isolates you a little bit.

A lot of people at that time expected I would not stay at Dartmouth, that I would just decide I wasn't up to it. It puts such thoughts in your head.

Another negative is that, obviously, forever after, every time you have a little ache and pain and every time you wake up in the morning having slept on your shoulder the wrong way, you begin to think, Is this it?

There are good things, though. Cancer did a couple of wonderful things for me. First, this community turned out to support me and to show me affection in ways that I might never have had an opportunity to experience, and that was wonderful. The second thing is that, by chance, I was asked to give two talks, and I got tremendous feedback from those speeches from other people who have had cancer. I suddenly discovered there's a community of cancer out there.

We have a student here now who has been diagnosed with lymphoma, which is what I have. He's had a bone marrow transplant. He called last week to say that next Monday, a week from today, is the first anniversary of the bone marrow transplant and could he come in and just share it with me?

He is doing okay, but he was 18 years old, a freshman, and he suddenly got lymphoma. We have become close, and his mother and I have become close. And I have become close now to a dozen people who have had cancer that I never would have known. I always get telephone calls from students saying, "Can I come on by?" They have cancer, or their brother has cancer, or their parent. I have met people I never would have. It helps me more than it helps them.

D.A.M.: When you went down to Boston and spent six months, were you champing at the bit to get back here, or was it still a question mark?

J.O.F.: No, never a question mark at that time. I wouldn't have taken the sabbatical if I thought I wouldn't come back.

D.A.M.: Did you do the job differently once you were back?

J.O.F.: No. I said that to myself: I'm going to change my priorities, I'm going to have more time for me, I'm going to slow down. I haven't been able to do any of that because you are who you are—you're compulsive, you're this, you're that. I just haven't much changed in that respect.

D.A.M.: Has that been wise? Look at what happened to [Harvard President Neil] Rudenstine [who took a leave of absence in 1995 when physical exhaustion floored him].

J.O.F.: A valid point. One of the things Vartan [Gregorian, former president of Brown] says is, "Physical fatigue I can take, but mental fatigue destroys you." He also says these jobs kill you and, of course, the Rudenstine episode affected all of us. It suddenly said to us: We're all skating on the-edge. He just had the misfortune to be the guy who fell over. What scared so many of us was, there but for the grace of God go we.

D.A.M.: Have you ever felt that you were getting close to that?

J.O.F.: No. I felt lots of times tired and exhausted, but I never felt I was getting close to that. Even through the six months of chemotherapy, I came into work every single day. I didn't always stay all day; I often went home at two or three o'clock. But I just thought it was fatal not to. I don't mean it's "fatal"—that's a bad word—but it would have been discouraging not to come into work. I just thought it was important for my morale to come to work every single day.

D.A.M.: And exhaustion has nothing to do with your decision to retire now? J.O.F.: No. My health is not playing a role. I will say that I did not want the cancer to recur someday and be left with regrets that I didn't do something I truly wanted to do.

D.A.M.: Are there any large initiatives you're still pursuing in your last months at Parkhurst, or that you'd like to see the College pursue after you've left?

J.O.F.: You know, if money were no concern, there are a number of things I would love us to do. The first is to have many, many fellowships for study abroad upon graduation. We have now the Reynolds. That gives five students a chance to go abroad. I'd love to have 25 of those. Let students spend a year at Oxford or Barcelona or Rome or Beijing or wherever they want to go for a year. Let them broaden themselves. We tried to endow that in the capital campaign and didn't succeed.

A second thing I'd like to see is very modest, which is some courses in Holocaust studies. Another thing I would like to see is some way in which we could formalize without stigma the opportunity for students to take a year or two off during the course of four years. When you talk to students who have been away for a year or two, they come back so much stronger, so much more mature. A year or two years makes a difference. But I think an awful lot of students find them-selves on a procrustean bed: They must get through, they must get on with earning, they must get on with life. But it might do wonders for them to have a year off and work in VISTA, or work in the White House, or paint pictures, or do any number of things—mature a bit, grow up a bit.

D.A.M.: Who makes that bed for them? Is it the parents?

J.O.F.: I think it's a lack of imagination in some cases, and I think sometimes there's parental pressure.

D.A.M.: Is there anything else on the table as you depart?

J.O.F.: We're starting a program in Jewish studies that I hope will continue to mature. We've gotten support through the capital campaign for that.

DAM.: In areas like that, does the College have to beware? I'm thinking of the Larry Kramer case at Yale [in which the playwright offered to underwrite gay studies and the university declined the gift since it was so topic-specific].

J.O.F.: It happens occasionally because alumni have very focused views of what they want sometimes. It isn't a question of whether, today, that would be fully appropriate or not, but you don't want to reduce the flexibility of the College in the long term. Take my favorite author, Faulkner. Suppose someone said, I'd like to give you a chair in Faulkner studies. A question is, how many people are engaged in Faulkner studies? A second question is, 50 years from now will people regard Faulkner as first rank? You don't know. So you have to be careful about people wanting to give you gifts that are too narrow.

D.A.M.: Do we take some gifts that are specified?

J.O.F.: We do because they seem consistent and appropriate. You go back and forth with donors. From time to time we decline gifts when we can't seem to work out a proper accommodation.

D.A.M.: Well, you won't have to worry about those negotiations much longer. What will you do after leaving this job?

J.O.F.: I have two tugs. I want to write some more. I want to do another book on liberal education and I'm more than halfway through that. And I want to do another book that I've written 500 pages of, but I'm not a tenth of the way there. Sol want to write, and I'm retiring at a point when I will still have a lot of time to write.

And I want to do something I haven't done since college, which is immerse myself in one author, just luxuriate in that one author. There are three possibilities. One is, of course, Shakespeare, which is endless and fascinating—you could read and read and read and read. The others are Faulkner and Joyce. I would love to spend four or five years just learning all I could about Joyce.

But, gosh, that's nowhere in present sight. I'm 62, which ought to mean that I've got a good number of years still to go. For now, the sabbatical, the writing, and then, in a year, a return to teaching on the Dartmouth faculty.

D.A.M.: What do you feel when you look back on these 11 years?

J.O.F.: I'm certainly gratified. This is still a place where a president can have an impact. There are institutions so big that I don't think a president has much of an opportunity to have an impact on the place. I think this is a place of a scale that, if you care enough and you're lucky enough, you can have an impact.

D.A.M.: Is Dartmouth wholly in synch right now, or are there still tensions?

J.O.F.: There's certainly very little tension. This is a product of a number of things. This is just a quieter time. Nationally we don't have great national debates or large issues, maybe to our discredit. But it's a quieter time generally.

I think people are very proud of Dartmouth's standing, and U.S. News has helped to confirm that.

Whether this is a factor, I don't know, but I am a great believer in the written word, and every year for 11 years I've published a little collection of my speeches. I write a column in the AlumniMagazine. I do lots of op-ed pieces which many of our alumni and others see. I wrote a book. I just feel if you explain yourself, maybe you can begin to unify people, because they get a common sense of what it is you're trying to achieve.

If there's been one central theme, it's been the value of liberal education. We should be a beacon, and we should hold high the standard for a liberal education.

D.A.M.: Have you had fun here?

J.O.F.: Sure. We've made wonderful friends here. Obviously Dartmouth is this tightly-knit community, and I've made friends I never would have made if we hadn't come back to New Hampshire.

D.A.M.: You're an insider now.

J.O.F.: I don't know.

D.A.M.: Well, do you feel like an outsider anymore?

J.O.F.: Not to the degree I did when I came, obviously. I feel like this is my place now. But I think we've still got a way to go before I'm fully embraced. I think we're two-thirds of the way there, but—it's a little like New England it-self. If you haven't lived in a town in New England for four generations, you're really not a part of that town. But I think we're getting there. I feel like I belong.

D.A.M.: Will you stay in Hanover from here on in?

J.O.F.: I think so. I can't imagine having better medical care and better access to a library and better colleagues than in a community like this. So, I think the high likelihood is we will remain here.

The trick will be to keep out of the hair of the next president. The trouble in this town is, every dinner party is about Dartmouth, and everyone wants to ask the old president how the new president's doing.

D.A.M.: What is the prescription for the next president?

J.O.F.: Well, it's funny—l say this humorously, but my experience is that many, many searches for presidents are searches for someone who solves all of the deficiencies of the prior president. If he was quiet, you want someone who's an extrovert. If he was an extrovert, you want someone who's going to slow down. If he was great at fund raising, you want a scholar. If he was a scholar, you want someone who can raise money.

People will tell you that what Dartmouth needs now is whatever I haven't done—because it doesn't interest me, or I'm not good at it, or I failed at it. I think the job for the next president will be to do those things. And, for me, the trick will be to stay out of his

Contributing editor ROBERT SULLIVAN is assistant managing editor of Life magazine.

JOF's GPA WHAT HE SAID "The efforts to achieve diversity on many college campuses are thus an essential part of achieving America's promise. We need to support them with a vigor and fidelity that reflect their importance to America's future." Editorial in The Boston Globe, August 1991 How HE DID • Entering classes reached gender parity during the Freedman years; the class of 1999 was the first in Dartmouth history to include more women than men. • The class of 2001 has the largest minority representation (25-4 percent) in Dartmouth's history.

JOFs GPA WHAT HE SAID "We must facilitate the enrollment of students from foreign countries in order to increase the cultural and ethnic diversity of the College." Inaugural Speech, 1987 How HE DID • Number of international students on campus in 1987: 244 • Number of international students on campus in 1998: 476

JOF's GPA WHAT HE SAID "Distinction in teaching and scholarship is the source of our vitality as an institution. We must continue to insist, therefore, that the standards we apply in appointing new faculty members and in promoting and granting tenure to junior faculty members are as rigorous as we can make them. They must be standards that reflect the most exacting levels of national and international achievement." —Speech to the faculty, 1987 How HE DID • Number of grants and contracts and their value awarded to Dartmouth in 1987: 337 awards; $31-7 million. • Number of grants and contracts and their value awarded to Dartmouth in 1997: 648 awards; $78.3 million • Percentage of faculty holding doctorates or equivalent terminal degrees: 99. • Dartmouth was #I in the 1995 U.S. News & World Report ranking of teaching. (The magazine no longer ranks that category.) Since U.S. News began its widely influential ratings in 1986, Dartmouth has regularly ranked among the top ten national universities overall.

JOF's GPA WHAT HE SAID "We must forever remember that a culture without art can hardly be called a culture at all. That is why it is essential that a liberal education fully embrace the visual and performing arts. That is why the Hopkins Center and the Hood Museum play such an essential role in Dartmouth's commonwealth of liberal learning." Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, May 1996 How HE DID • Number of majors in music, studio art, film, and drama in 1987: 22 • Number of majors in music, studio art, film, and drama in 1998: 81 • Number of objects in the Hood Museum in 1987: 53,678 • Number of objects in the Hood Museum in 1998: 60,000

JOF's GPA WHAT HE SAID "We must continue to offer students an opportunity to widen their angles of vision on the world by infusing our curriculum with an international perspective and by emphasizing the study of foreign languages." Inaugural speech, 1987 How HE DID • Number of LSA /FSA programs in 1987: 39 • Number of LSA/FSA programs in 1997: 34 • Number of students enrolled in LSA/FSA in 1987: 679 • Number of students enrolled in LSA/FSA in 1997: 498 • Number of languages taught in 1987: 9 • Number of languages taught in 1998: 12

JOF's CPA WHAT HE SAID "Dartmouth has a moral obligation and civic responsibility to do all it can to make the benefits of a Dartmouth education available to qualified students regardless of financial need," Dartmouth Alumni Magazine,1991 How HE DID • Financial aid awarded in 1987: $11,720,000 • Financial aid awarded in 1997: $26,446,000 • Students awarded aid in 1987: 1,496 • Students awarded aid in 1997: 1,770 • Even so, Tuition Hikes continue to significantly outpace the Consumer Price

JOF's GPA WHAT HE SAID "We must continue to pay particular attention to attracting the strongest possible student body to Dartmouth." Speech to the Faculty, 1992 How HE DID • During Freedman's tenure the mean SAT verbal and math scores of the incoming class increased by 18 and 25 points, respectively. • The number of enrolling high school valedictorians increased by 75 percent during the same period. • The first comprehensive overhaul of the Dartmouth curriculum in more than 70 years was implemented in the fall of 1993. • Dartmouth received the highest number of undergraduate applications in its history —approximately 11,400 for just over 1,000 places in the class of 2000. Five years earlier, applications for the class of 1996 had totaled 8,076 for approximately the same number of places, which even at that level made Dartmouth one of the most highly selective higher-education institutions in the country.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWhat Comes NEXT

June 1998 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

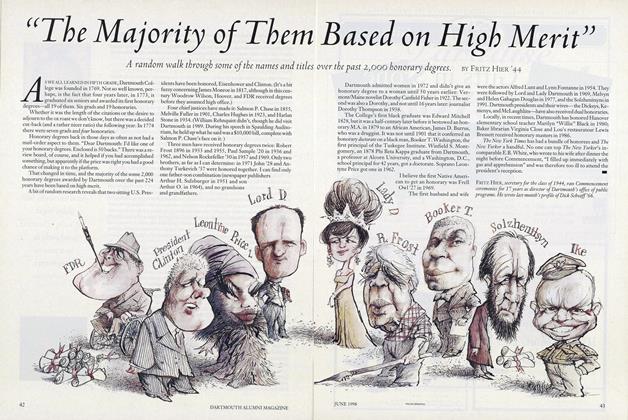

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

June 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleThe Gospel According to Odysseus

June 1998 By Professor William Scott -

Article

ArticleBack to the Future

June 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleNewt ana Other Spring Speakers

June 1998 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

June 1998 By Don Casey Jr.