Darmouth must keep changing to remain the same.

MOVING TOWARD the conclusion of my tenure as president of Dartmouth, I am prompted to reflect upon one of the most important lessons I have learned during these last 11 years.

That lesson is summed up in a sentence from a novel, The Leopard, by the Italian writer Guiseppe di Lampedusa: "If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change."

If we want Dartmouth to remain as it is—in terms of its character, its values, its aspirations for excellence, its ambitions for its students—then we must take care that, as the times change, the College changes, too.

One way to illustrate this point is to consider four 25th anniversaries that we have celebrated this academic year. Each commemorates what was at the time a dramatic—even controversial—change. Now we can see that each of these changes, in fact, strengthened our character, enhanced our values, and reinforced all that is important about the College.

The first of those celebrations, held last fall, commemorated coeducation. Several hundred alumnae returned to the College, many for the first time. We reflected upon the fact that Dartmouth is now a fully coeducational institution in which the student body is 48 or 49 percent female. President Kemeny once told me that of all the major decisions he had made during his 11 years as president, the one of which he was most certain was that Dartmouth needed to become coeducational if it were to continue to serve its historic function of preparing the future leaders of this country.

Because of John Kemeny's leadership, Dartmouth became coeducational, and we are now educating women as well as men. The quality of the education that we offer has been greatly enriched by the presence of female students on the campus. Coeducation changed Dartmouth, but it changed it in ways that permitted Dartmouth's values to emerge stronger than they had been before.

The second anniversary we celebrated was that of our Native American Program. It, too, is a product of the imagination and courage of President Kemeny. It was in his inaugural address that President Kemeny called for the establishment of the Native American Program at Dartmouth, reminding us of the promise implicit in Dartmouth's royal charter, which recited that the purpose of this new college that Eleazer Wheelock proposed to found was to educate Indian youth, among others—a promise that Dartmouth had honored primarily in the breach over the first 200 years of its existence.

Since President Kemeny's call to action, Dartmouth has established perhaps the leading Native American studies program in the country. Each year we admit approximately 30 Native American students who, too, go on to make contributions to their communities and to this country. By that program, we are keeping faith with the original purposes set forth in Dartmouth's charter, as well as responding to an important national need, the education of Native American women and men.

The third anniversary that we observed this year was that of the Black Alumni at Dartmouth Association. Twenty-five years ago there would hardly have been a need for such an association; most classes, even into the 1960s, included no more than two or three African Americans. It was not until the late 1960s that Dartmouth truly committed itself to racial diversity—to educating students of all racial backgrounds so that we could truly say that we were helping to prepare for national leadership students of all of America's races, creeds, and colors.

Our Black Alumni Association is now a vibrant organization, and Dartmouth is a stronger place because African-American students have come to Hanover and made their contributions to our classrooms, to our campus activities, and most of all, in due course to our nation.

Finally, this year is the 25th anniversary of our academic program in environmental studies. Environmental studies is one of those subjects that hardly existed 25 years ago. Now it exists at colleges and universities across the country. One can hardly think of an area more appropriate for Dartmouth to emphasize than environmental studies.

The anniversary of environmental studies reminds us that the world of knowledge changes, and changes rapidly. New subjects enter the curriculum, others fall away, and still others take different shapes. Institutions like Dartmouth must change to accommodate themselves to this new knowledge, as we have not only in environmental studies but also in the breath-taking new areas of biology, in African-American studies, in Latin-American, Latino, and Caribbean studies, in Jewish studies, and in women's studies—in all those areas of knowledge that require us to adapt the curriculum in order to maintain the basic values of Dartmouth as an institution at the forefront of the search for knowledge.

I mention these four anniversaries because what I have learned most in these last 11 years at Dartmouth is that a college must change to stay the same in a changing world, even as one must row hard to hold one's own against the tide.

Dartmouth had to respond to the needs of coeducation; we had to respond to the imperative to make available the College's incalculable educational opportunities to Native American students and to African-American students. We had to respond to changes in the world of learning to establish new courses, new programs, new departments, as we did in environmental studies. In doing so, we preserved not only Dartmouth's character but also its fundamental purpose.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

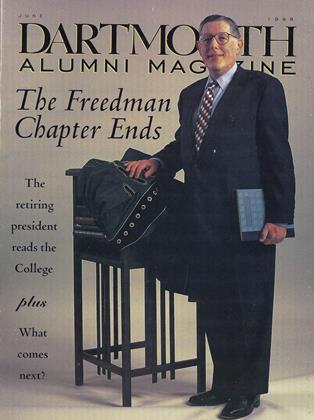

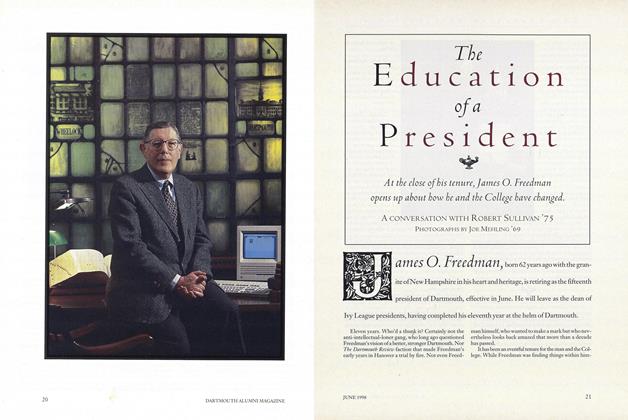

Cover StoryThe Education of a President

June 1998 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Comes NEXT

June 1998 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

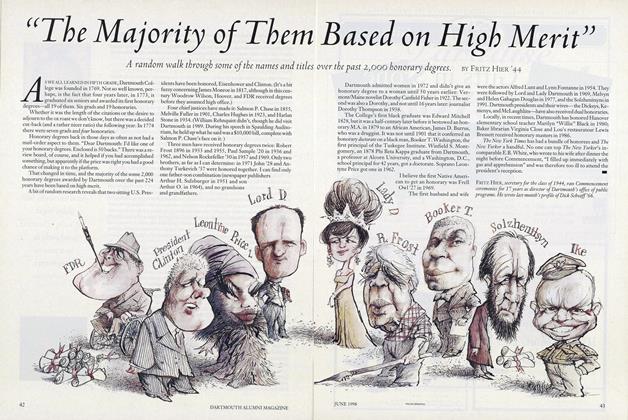

Feature"The Majority of Them Based on High Merit"

June 1998 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Article

ArticleThe Gospel According to Odysseus

June 1998 By Professor William Scott -

Article

ArticleNewt ana Other Spring Speakers

June 1998 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

June 1998 By Don Casey Jr.

James O. Freedman

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs "The College" a College?

December 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleORIGINALS AND COPIES

JUNE 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Trembling Hope

APRIL 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleSkepticism and the Refined Mind

SEPTEMBER 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWomen and Men of Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1997 By James O. Freedman