QUOTE/UNQUOTE "What we're realty trying to do is build an immune system for the Internet." LEWIS DUNCAN, DEAN OF THAYER SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING

IN THEIR DIGS AT 45 LYME ROAD, just across from the Hanover Police Department, 25 researchers at Dartmouth's new Institute for Security Technology Studies operate at the edge of information technology—and, too, at the edge of crime. They patrol a shadowy electronic frontier where a rogue hacker can hold Yahoo! hostage, where a university student in the Philippines can cripple 45 million computers around the globe.

These experts dwell in the increasingly consequential realm known as cyberterrorism. And man, they can seem awfully secretive about it.

When we sought intelligence on the institute from Lewis Duncan, dean of the Thayer School of Engineering, his assistant suggested calling Richard Scribner, the institutes acting directorthen proposed a chat with College deputy provost Jamshed Bharucha. George Cybenko, the engineering professor who heads a hefty chunk of the institute's research, refused to speak until Scribner had been contacted—and even then, he proved elusive. David Nicol, who runs another chunk, was traveling. Scribner himself didn't return calls for days; Bharucha was said to be away on vacation.

Eventually, the institutes principals surfaced—swearing they were not so much clandestine as modest. Duncan, who worked with Sen. Judd Gregg, RN.H., to form the institute, envisions the emergence of a very public national center whose research will be both widely cited and widely applied. "When it comes to cybersecurity, it will be a Dartmouth professor or researcher who's being quoted on the front page of The NewYork Times," he says. But for now, Scribner says, "We've barely started. Let's not blow our horn until we have results worth touting."

In its earliest days, the institute had fair cause to lay low. It was born last March, thanks to a sis-million federal appropriation spearheaded by Gregg. The intent was to promote work that would help buttress Internet security, a worthy enough mission. Yet because Dartmouth didn't compete for the funding with other institutions, some critics derided the grant as political pork.

Now, however, the institute's viability appears relatively firm. Federal money actually has appeared in College coffers, and Scribner expects another $15 million will be granted next year. The institute has begun hiring aggressively—it expects to employ 60 people by the middle of next year and to recruit participating faculty from across the College. More important, it has organized a research network thus far of 11 institutions, among them Harvard, Stanford, Carnegie Mellon, the Los Alamos National Laboratory and software pioneer BBN Technologies.

All this is an ambitious undertaking. If it succeeds, the institute will produce high-level theoretical research that sets the national cybersecurity agenda. But it also will develop the practical tools needed to combat such crime. "We will be successful if we improve national capabilities in countering cybercrime and cyberterrorism and earn an international reputation for leadership in these areas," says Cybenko. "People must understand that there are no 'silver bullets' in this area. Technology is changing and creating new vulnerabilities. It's a rapidly moving target."

Cybenko, an expert in distributed information systems, discovered a method for encoding a program so that it can be executed in encrypted form by another computer without decrypting. The output is encrypted as well. This is expected to be useful for e-commerce (sending bidding strategies to auction sites, for example), network computing and networked sensors. These are situations in which the computer may not be known to be secure. He also plans workshops to train investigators in cyberdetection strategies.

Likewise, Nicol, a computer science professor, is working on software, derived from programs already in use at Thayer, that will allow systems administrators to model and simulate complex security problems. What happens, for example, when a hacker mounts a "denial of service" attack that threatens to shut down an Internet service provider? How can the provider respond effectively, and what will be the side effects of its actions on the network? "People recognize that these vulnerabilities exist," says Nicol. "But no one knows how the complex systems will respond." If his work pans out, organizations might answer such questions minutes after a threat appears.

That's what's happening now on Lyme Road. And the longer-term prospects are even more intriguing. For example, the institute is funding scientists at Los Alamos whose fledgling technology appears capable of analyzing the content of a computer disk even after it has been erased.

There is enormous commercial potential in such stuff, and Duncan says the school already has been approached by companies interested in forging research relationships. But the institute also wants to, well, save the world. "When teenagers can bring the system to a halt," Duncan says, "you have to realize that we're extremely vulnerable."

Crime Stopper Professor Cybenko isdeveloping a constantly updatedWeb site to aid FBI agents and policein the pursuit of online offenders.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

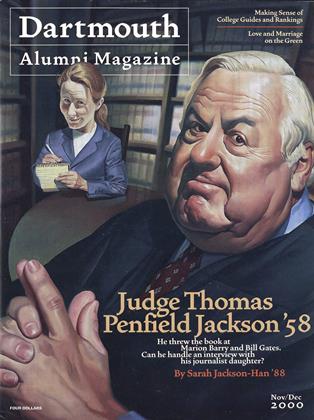

Cover Story

Cover StoryFather In Law

November | December 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

November | December 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

November | December 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

November | December 2000