Responding to the economy's toll on the endowment, the College trims its budget and priorities.

FOR THE PAST FEW YEARS, FINANCIAL markets across the world have experienced a wild ride—down 400 points one day, up 200 the next. We have all seen the effect this has had on our savings and retirements funds. And certainly Dartmouth is not immune from market forces. In the late 1990s the Colleges endowment did very well, growing from less than a billion dollars in 1995 to more than $2 billion in 1999. The 2000-2001 fiscal year saw 346 percent return on the endowment—an incredible return in a buoyant market.

Since then, our investments have performed well against benchmarks, but the growth has temporarily halted. Our endowment lost a slight amount in 2001 and lost 5.7 percent of its value this past year, leaving us with projected budget deficits for 2003 and 2004. One question that I get asked is: Why can't we use the run-up in the endowment in the late 1990s to cover the projected shortfalls now?

Dartmouth's endowment, built up through the generosity of alumni over more than two centuries, stands at $2.2 billion. It is held in trust to secure the education of current and future generations of students. Each year Dartmouth distributes some portion of the income from the endowment to departments around the College. In distributing that income, we follow a complicated formula that relies on a 12-quarter rolling average, which evens out market fluctuations to provide a more predictable flow of revenue.

The College typically distributes between 4 and 6 percent of the market value of the endowment, and the money distributed goes toward the support of a wide range of activities including financial aid, academic programs and faculty salaries. Although we talk about the endowment as if it is a singular entity, it is, in fact, made up of hundreds of smaller funds, most of which are restricted in some form or another. Most of the increase in the endowment in the late 1990s, for example, went into restricted funds, such as scholarship funds and endowed professorships. The unrestricted portion of the endowment provides income to the central budget, money that helps to pay for new initiatives as well as unavoidable expenses such as increases in health-care premiums.

In the late 1990s, as a result of strong returns, we were able to move ahead with several priorities. We twice enhanced our financial-aid program. We increased faculty and staff compensation and graduate student stipends to remain competitive with the market. We helped pay for important renovations to academic facilities. We built McCulloch Hall for undergraduates. We increased staff in the library, grants and contracts, computing and in the dean of the college area to provide more support to students. And we enhanced support for athletic programs. The money was well spent—it helped to ensure the continued quality of the Dartmouth experience for all students.

The increase in the endowment also allowed us to keep tuition increases to a minimum. In 1990 endowment income paid for just 15 percent of the educational and general expenses of the College. Today it pays for 30 percent of those expenses, reducing the Colleges reliance on tuition to cover costs. Generally speaking, the increasing dependence upon endowment rather than tuition is a good thing as we work to keep a Dartmouth education fully accessible. But it has left us more vulnerable to a downturn in the market.

Now, to bring the budget into balance, we need to reduce our expenses. It is never easy to cut. We must do so thoughtfully and carefully in order to protect those things that are most critical to the academic enterprise.

This past summer I announced two rounds of budget reductions. Most administrative areas will reduce their budgets by 4 percent. To protect the academic program as much as possible, I have reallocated presidential reserves of $1 million per year to this area and have kept its reduction to 1.4 percent. I have also made an allocation to the dean of the college area that will result in a budget reduction of only 2.6 percent. The provost area, which includes the library, computing, the Hopkins Center, the Tucker Foundation and the Hood Museum, will reduce its budget by 3.3 percent. In addition, at my request, the budget committee chaired by the provost has begun to review all open or new non-faculty positions and has placed a hold on construction projects. As we hire new staff and as we move forward with our facilities projects, we need to be sure that we have full funding in place.

Despite the shortfall in revenues, we continue to advance our strategic plan with its emphasis on faculty, student life and facilities. We remain fully committed to need-blind admissions and our financial-aid program. We are also proceeding with planning for the next capital campaign, although we must acknowledge that its shape and timing will need to be sensitive to economic conditions. Dartmouth alumni continue to support the College in so many ways, and their generosity is a critical part of our strength. We may need to delay some things in order to have full funding, but we will not step away from the commitments we have made toward making Dartmouth ever stronger. Our students deserve a Dartmouth experience that is of the highest quality.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

November | December 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

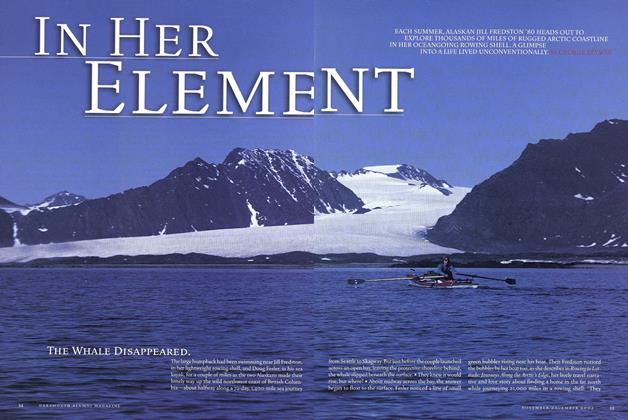

FeatureIn Her Element

November | December 2002 By GEORGE BRYSON -

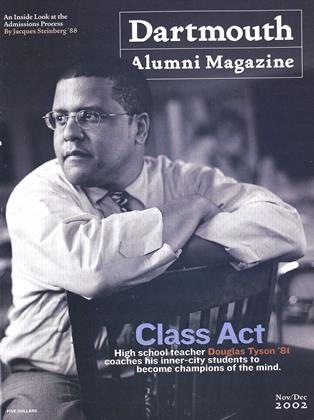

Cover Story

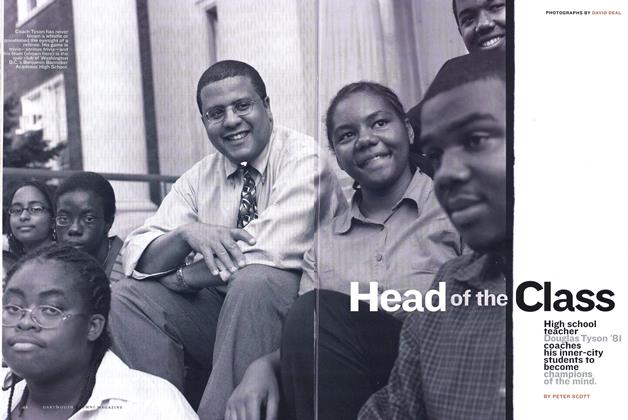

Cover StoryHead of the Class

November | December 2002 By PETER SCOTT -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Iraq Question

November | December 2002 By Daryl G. Press -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

November | December 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Outside

OutsideThe Literature of the Logbooks

November | December 2002 By Madeleine Eno

President James Wright

-

Article

ArticleTeamwork

OCTOBER 1999 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleWhere Do We Go From Here?

JANUARY 2000 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleThe Global College

Jan/Feb 2001 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleDollars and Sense

July/August 2001 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleVirtue and Achievement

Sept/Oct 2001 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleShock Waves

Jan/Feb 2002 By President James Wright

Article

-

Article

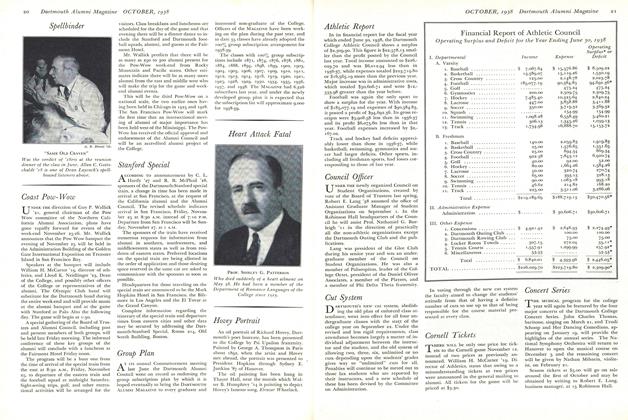

ArticleConcert Series

October 1938 -

Article

ArticleIndustrial Educator

January 1941 -

Article

ArticleAdministrative Appointments

OCTOBER 1965 -

Article

ArticleMOOSILAUKE

MAY 1927 By Daniel P. Hatch, Jr. '28 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

May 1946 By Parker Merrow '25. -

Article

ArticleThe Commencement Address

July 1953 By THE HON. LESTER B. PEARSON '53h