Bring Back the Vox!

The new Berry Library might do well to consider reviving some of Baker Library’s lost traditions.

Sept/Oct 2000 Noel PerrinThe new Berry Library might do well to consider reviving some of Baker Library’s lost traditions.

Sept/Oct 2000 Noel PerrinThe new Berry Library might do well to consider reviving some of Baker Library's lost traditions.

SEVEN TIMES IN ITS LONG history, the College's library has gone through a transition. Seven times it has outgrown its home and moved to a larger one, not unlike a blue crab shedding its exoskeleton in favor of the next size up.

The tiny original libraryoccupied a few shelves in professor Bezaleel Woodwards house. After a few years the books got carried to a small room in College Hall, and that was the first transition. In the second, they got a larger room in President Wheelocks house. In the third they were lugged into Dartmouth Hall. And so on. Finally, we come to the current transition: the $66.5-mil lion building of Berry Library and renovation of Baker Library.

None of the early moves was major. In 1800 the entire library of Dartmouth College could have been put in 100 packing boxes, 30 books to the box. It would take more than 30,000 boxes now.

In these last 200 years the library has done some wonderful things—and some remarkably foolish ones. I think the most foolish may be the period in the early 19th century when the library was open to undergraduates one hour every two weeks—and there was talk of keeping them out altogether.

As for wonderful things, I want to describe just two, giving them each a scene.

Scene One: Main corridor of BakerLibrary. A little knot of students stands in front of one of the tall glass display cases. They are looking at the books inside. There are just five, each mounted like a very large butterfly, and each accompanied by two or three sentences of praise, neatly typed on a card.

It's the praise that has attracted the students. The library runs a program called Faculty Favorites. Several brary invites some prof or dean to pick five books that he or she especially loves and explain why in a sentence or two. Then it's into the window.

The current display consists of five books chosen by English professor Peter Saccio, one of the country's premier Shakespeareans. Several hundred students on campus have taken a course with Saccio, and many hundreds more know him by reputation. Students are often curious about their teachers' private tastes, and the Saccio display has been drawing well.

Scene Two: Entrance to the reserve corridor. A little knot of students and one faculty member are standing in front of a large bulletin board, which is fixed to the wall. Next to it is a large wooden box with a slot in the top. Under the slot the word "Vox" appears. And on the board many scraps of paper are pinned, each asking a question of the mysterious entity known to the students as "Vox in the Box." No one has ever seen Vox come out of his box and pin the questions up; no one has ever spotted him or her composing the witty and well-in-formed answers appended to each question. But many people regularly stop to read them.

Originally Vox was a standard suggestion box. The scraps of paper that students pushed through the slot were supposed to comment on or ask questions about library matters only.

But Vox's answers so delighted the undergraduates that they began asking questions further and further away from matters such as reserve corridor hours. For example, they have asked Vox if it's true that there is a wide variation in the alcohol content of the leading American beers. There's variation, but it's not wide, Vox answered, and proceeded to give percentages for six common brands.

"Does God exist?" another student asked. Stripped of its wit, erudition and details, Vox's answer was quite simple: "Opinions differ."

"How many colleges are older than Dartmouth?" asked a quantitatively minded student. "Ten," Vox informed him, and listed them. Vox could have added, but didn't, that there are about 1,740 younger ones.

There's just one problem with these two scenes. They are imaginary. There are no Faculty Favorites displays any more, haven't been for a long time. There is still a Vox box appended to the wall, but it has been empty since 1991. The bulletin board hangs where it always hung, but it is entirely blank. Why? Rumor has it that the powers-that-be decided that it was taking too much of one librarian's time to answer all those questions. Solution: Drop the box.

According to a much fainter rumor coming from a still earlier time, the li-brary dropped the Faculty Favorites because the powers-that-be had engaged a professional window-display designer who felt that stuff like that was pitifully amateurish.

Does the library have a death wish, even as it is getting a new multi-million dollar exoskeleton? Vox was beloved. It was also the best PRa library could have. More than that, the Qs and As were intellectually stimulating and as much a part of a Dartmouth liberal education as anything that happens in a classroom. Even if it had taken the combined efforts of two or three librarians instead of one librarian part-time, it would have been worth it.

As for Faculty Favorites, not all of us on the faculty are as witty and fun to read as the invisible librarian behind Vox. But some are. And even a Favorites note written in the style called High Theoretic would get through to some students.

Our library, like every other academic library, is facing not declining usage, but declining personal presence of patrons. How many students can dance down the main corridor of Baker? A lot more than actually go there.

You still have to be physically present in order to take a book out. But to consult the catalog? Check Books in Print? Research your paper? Who needs to trudge over to Baker-Berry? You can access all that from your dorm room.

I don't really think the library has a death wish. I do think it's an outstanding library—in fact one of the best college libraries in the world. But I also think that the powers-that-be have made a couple of idiotic decisions.

Now would be the perfect moment to undo them. Any institution is at its most flexible during a transition moment. (How do you think we got rid of that old rule about visiting the library only one hour every two weeks?)

If the powers-that-be have any sense, they will celebrate the seventh transition by restoring Vox to his box, and they will invite some nimble professor or even a nimble dean to pick five books that he or she delights in. Then they will mount a display. And it won't cost a cent.

NOEL PERRIN is an adjunct professor of environmental studies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

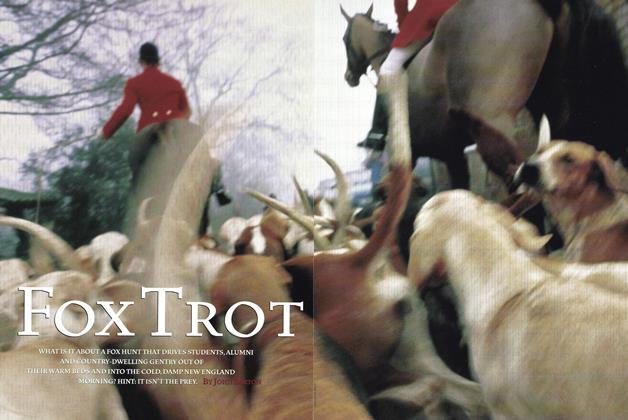

FeatureFox Trot

September | October 2000 By John Barton -

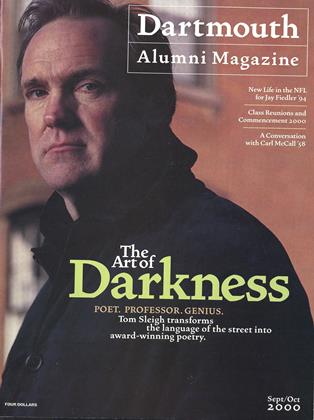

Cover Story

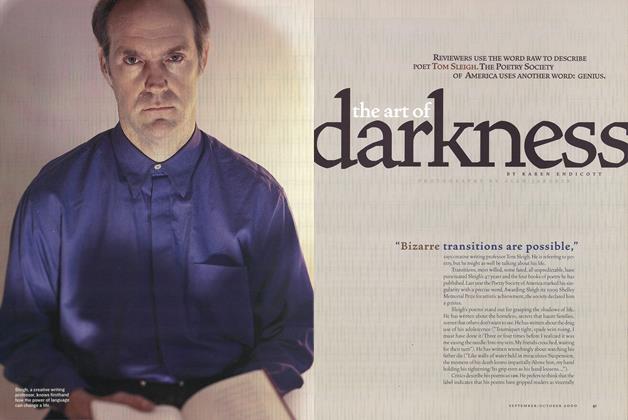

Cover StoryThe Art of Darkness

September | October 2000 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Feature

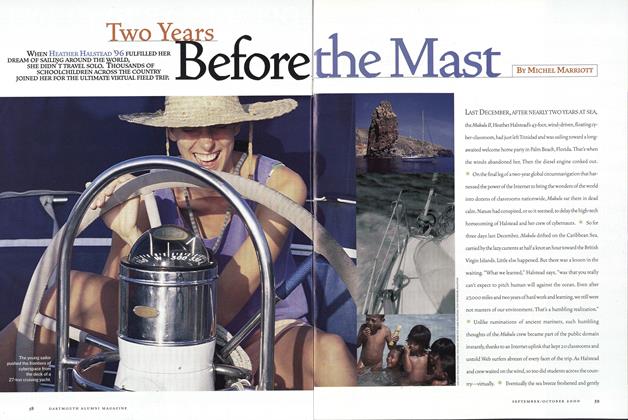

FeatureTwo Years Before The Mast

September | October 2000 By Michel Marriott -

Feature

FeatureCommencement and Reunions: A Sketchbook

September | October 2000 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYWhat is Perfect?

September | October 2000 By Mary Cleary Kiely ’79 -

Sports

SportsMaking all the Right Moves

September | October 2000 By Brad Parks '96

Noel Perrin

-

Books

BooksTHE CHRISTENING PARTY.

February 1961 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

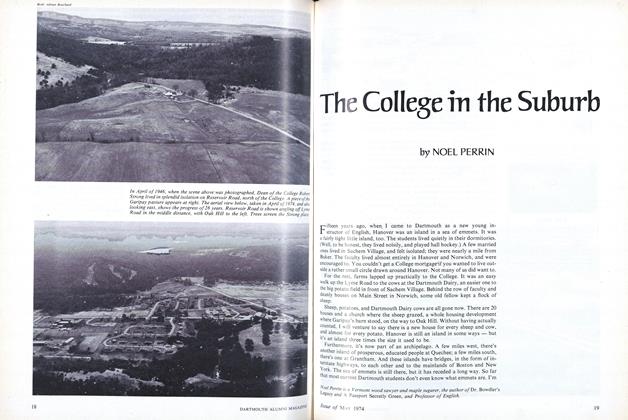

FeatureThe College in the Suburb

May 1974 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleThe Prize Nobody Wins

JUNE 1978 By NOEL PERRIN -

Cover Story

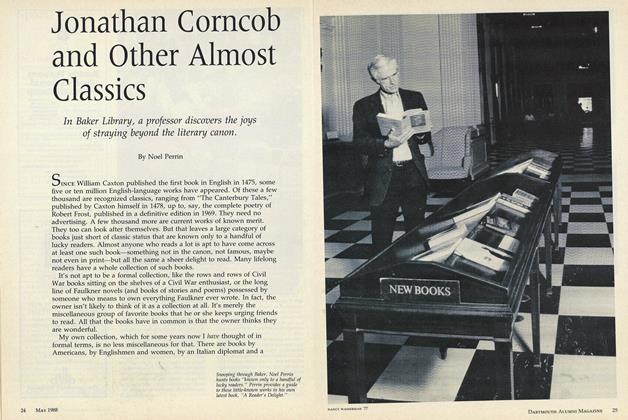

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

MAY • 1988 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleCoaching

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONSkating on Thin Ice

MARCH 2000 By Noel Perrin