Harness The Gym Rats

Students who spend hours working out could be the answer to the next energy crisis.

Nov/Dec 2000 Noel PerrinStudents who spend hours working out could be the answer to the next energy crisis.

Nov/Dec 2000 Noel PerrinStudents who spend hours working out could be the answer to the next energy crisis.

[F YOU'RE OUT EARLY IN THE morning, what do you see on our local roads? You see joggers. You also see people walking their dogs. Neither group, of course, is going anywhere. If an American is going somewhere, he or she naturally drives.

One place that a lot of people drive to is a health club. There are about 10 of these in the Hanover-Lebanon-Woodstock area—and that's not counting Dartmouth's own superbly equipped Kresge Fitness Center.

What happens after they park and go in? Well, it's like the roads, only more so. Here people jog on treadmills, moving in place. At great effort, they go nowhere. Here people also climb. They climb and they climb, and they never get any higher. Even Sisyphus used to get partway up his hill.

Here they also row. They row and they row, and the boat doesn't move an inch. There is no boat. There's an ergonomic machine. It's only pretend travel, but there sure is a lot of it.

There was a cold winter day—-January 31, 1998, to be precise—when the Dartmouth crews, men's and women's, each set a world record. Not on the Connecticut River, obviously, which tends to be iced over in January. These records were both set in Thayer Hall, where two rowing machines had been temporarily set up. In a 24-hour period, spelling each other constantly, the men rowed the equivalent of 498 kilometers—enough for a trip to New York. The women pulled the equivalent of 413 kilometers. But how odd to set a Guinness-style record without ever leaving campus. Perhaps the virtual marathon will come next.

well-run center provides expert supervision, useful measurements, the support of a peer group. But there is one way in which all these machine rooms could use a little improvement. Right now human beings drive to the centers, using gas. (Yes, even some to Kresge.) Once there, they run to the machines and start maximizing productivity. But what do they produce? Except for muscle tone in their bodies, and sometimes an ego boost, nothing. Mind you, I don't mean to be at- tacking either fitness or the centers. A healthy body is an excellent thing. A

What we are witnessing nowthough not as yet in fitness centers—is the slow but steady growth of conservation ethics. A conservationist would look admiringly at Kresge, maybe try one of the new elliptical trainers that are so much easier on the knees than the treadmills they are replacing, and then ask: "Why couldn't these machines be doing something real?" For example, why couldn't they—as the rowers row and the treaders tread—be making a little electricity? I don't mean some kind of symbolic power, showing up only on a dial. I mean live watts, flowing from a small generator hooked to each machine, watts that do actual work. That would be a happy change from the present situation, where most fitness machines con- sume power. Not much. But it does take a little electricity to power the readouts and sometimes the resistance.

If the conservationist looking at Kresge happened to be a scholarly type—say a member of the Colleges history department—he or she might point out that treadmills have a long history of being useful. In 1818, for example, Sir William Cubitt began installing treadmills in British prisons. They mostly powered the milling of flour and the pumping of water. And like the Dartmouth crews setting their world records in 1998, the convicts in 1818 worked in spurts: 15 minutes on the wheel, 5 minutes of rest, 15 on the wheel, and so on.

Suppose Dartmouth (which, after all, was first endowed by an earl) decided to follow the example of a knight. Well, to begin with, there would be support from Alumni Gym. Roger Demment, the associate director of athletics, is the person who oversees Kresge. He and his colleagues have been joking for years about putting some of that wasted energy to work. Since nearly all the machines have readouts and can report how many calories a minute the exercise is burning off, and since calories can be translated into watts, there could even be a weekly prize for the student who generated the most electricity.

So if it's such a good idea, and if the powers in the athletic department would support it, why hasn't it happened?

There are two answers. First, it is an idea whose time is only just coming. Secondly, and this I report sadly, the amount of electricity that Kresge could generate is minuscule. Even when a hundred people are there (far more than powered one of Sir Williams big wheels), the amount is small. With a great deal of help from professor Charles Sullivan of the Thay- er School, I have a rough figure for what Kresge could produce: about 200 watts per person. Five hours of continuous workout—something no sane person would essay—would thus yield one kilowatt hour of electricity.

And what is a kilowatt hour worth? In New Hampshire, about 10 cents. If students were being paid to generate electricity at Kresge, their wages would be two cents an hour.

This figure can be prettied up, of course. For example, suppose the crews decided to keep the two rowing machines going all the time, thus setting yet another world record. Each year they'd make 9,000 kilowatt hours. Rowing machines would have a payback period of only two years.

The number of kilowatt hours isn't nearly as important as the fact that we're talking about the real world, the real world of global warming and air pollution. I predict that within five years the desire to get out of the playpen and into global reality will have led to at least half a dozen power-making machines in Kresge.

And the ridiculous two cents an hour? It's far outweighed by the knowledge that one is contributing to the solution, not the problem—and of course there are also the accolades and prizes the College would be offering, not to mention a whole new level of student competitiveness.

As I end, let me just mention something that is both practical and cheap right now, and there are parents doing it: You buy an exercise bike with the usual dials and gauges. Then you explain the new house rule to your children. They can watch all the Saturday cartoons they want. But first they have to hop on the bike and make enough electricity for however many shows they want to watch.

Couch potatoes no longer. Fit and healthy kids.

NOEL PERRIN is an adjunct professor of environmental studies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

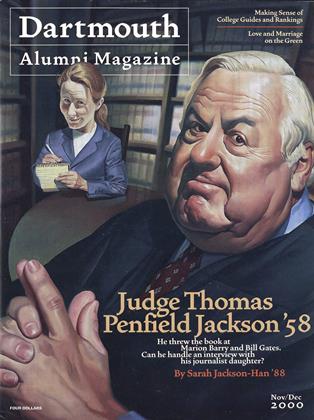

Cover StoryFather In Law

November | December 2000 By SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88 -

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

November | December 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

November | December 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

November | December 2000

Noel Perrin

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Books

BooksTHE CHRISTENING PARTY.

February 1961 By NOEL PERRIN -

Books

BooksTHE DISPLACED PERSON'S ALMANAC.

March 1962 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

FeatureThe College in the Suburb

May 1974 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONBring Back the Vox!

Sept/Oct 2000 By Noel Perrin