Paying the Price

How his decision to join the ROTC program during tumultuous times shaped one alumnus’ life.

Nov/Dec 2005 JEFF DUDYCHA ’93How his decision to join the ROTC program during tumultuous times shaped one alumnus’ life.

Nov/Dec 2005 JEFF DUDYCHA ’93How his decision to join the ROTC program during tumultuous times shaped one alumnus' life.

I CAME TO DARTMOUTH IN THE FALL of 1989 from small-town Wisconsin and found myself in a cohort of students who were genuinely excited by intellectual matters but did not let that overtake their lives. I was impressed at the scope of diversity in my compatriots—not the check-box diversity beloved by academic officials, but real, substantive diversity in achievements, perspectives and ambitions. From the beginning of my freshman trip in the Vermont hills, I was, and continue to be, confident that choosing Dartmouth was one of the best decisions I have made. But it was a choice that may have come at an uncommon price.

Because my parents were professors at a small public college and were unimpressed by Dartmouth's lack of meritbased scholarships, I had to figure out how to pay for it. Signing on to the ROTC program, which offered me a hefty scholarship, wasn't entirely out of character. I really did believe—and still do—that American military action is sometimes necessary for a better world, and I was glad to be a part of it. I planned to follow college with law school and a career in foreign relations and thought a stint in the Army would be a useful credential. When my career goals changed to biology, I stayed with the program for the scholarship. I didn't think much about what joining the Army meant for me personally. I looked at it as paying back student loans with time-eight years of it—rather than money.

I was a decent, but not stellar, cadet. I could meet the standards, and even do well when I put my mind to it, but I didn't have an intuitive talent for squad tactics. I was good with a map and compass and a crack shot with a rifle. Most importantly, I had perseverance. That was enough to get through.

My dependence on ROTC made me even more sensitive to the opposition the program faced on campus. Although I expected some folks to disapprove of it, I was stunned by the animosity directed at ROTC by some faculty and very vocal students. Ostensibly at issue was the exclusion of homosexuals by the Army, but I suspected part of it was just a general contempt for the military—at least that's what it felt like in a language class my sophomore year. The professor wanted to schedule a special conversation period that conflicted with ROTC drills. When I explained why I couldn't make it, she turned sour and thereafter refused to acknowledge me in class. Id raise my hand to ask a question, be ignored and then ask my question out loud, which would also be ignored. One of my classmates would ask the same question and get a prompt and considerate response.

Even aside from the ROTC issue it seemed to me that the gay community in Hanover, or at least its public face, was especially angry—at everyone. My exposure to homosexuals was only from media portrayals: the stereotypical frivolous fop played for laughs or pathos, and his alterego, the earnest activist bent on shattering the stereotype. At Dartmouth the few openly gay students I met were neither. However, the visible part of the gay community was dominated by a bitter obnoxiousness exemplified by the occasionally published, and accurately titled, In Your Face. In retrospect, I suspect shouting, "We're here, we're queer, get used to it!" at passers-by is probably less about being deliberately unpleasant than lashing out in frustration at a hostile world. Nonetheless, I saw the gay community as grounded in its own hostile belligerence. I couldn't believe that people could be so spiteful and I didn't want to be a part of anything they represented.

I had a problem, though. I was.

One night in my sophomore fall, as Diana Rosof'91 and I were walking across the Green from our rooms in Topliff to the Collis Cafe, Diana turned to me and asked, "Jeff, are you gay?"

"No," I replied, trying to sound neither too emphatic nor too panicked. A truthful answer at the time would have been, "I'm freaked out that the answer is yes, and I desperately never, ever want to think about it!" Dianas question set in motion a transformation of howl understood myself. It was that night that I stepped into the closet.

Being gay posed a definite problem for an ROTC cadet, and I did what many a queer has done: I simply refused to believe it. I didn't feel I could look to the College's gay organization for advice, because I didn't want to become part of its bitterness. Also, I figured it was more likely I'd be ostracized or, worse, outed, for not embracing left-wing activism than welcomed as a troubled kid coming to terms with himself.

Oddly, the Army dispelled my fears at the cadets' basic training we attended the summer after our junior year. Before our complete physical the sergeant in charge of my battalion spoke about the serious problems that gays caused in the military. He told us that a blood test would identify anyone who was gay and any gay cadets would be summarily kicked out of the Army. He also told us that anyone who wanted to admit to being homosexual could see him privately and quietly leave the Army with an honorable discharge.

I wasn't afraid of being kicked out. Instead, I saw an opportunity to get concrete proof one way or another as to my sexual orientation. When nothing happened to me after the physical, I was relieved to know that I really was straight. Of course, there was no blood test. The sergeant was bluffing. As a biologist, it's embarrassing to admit that it wasn't until a few years later, when I was well into my Ph.D. studies, that I let go of my faith in that fictitious blood test.

Denying my sexuality came mostly from my own hang-ups, but also my aversion to what I saw as a narrow-minded, left-wing gay community. The eight years I owed the Army made for an easy excuse to ignore being gay and to stay in the closet while I was a Medical Service Corps officer in the reserves.

Like lots of Dartmouth's superachievers, I grew up being told I could be anything I wanted and do anything I set my mind to. So I set out, through sheer force of will, to be straight. Even helped along over the years by the power of dozens of shooting stars, broken wishbones, fallen eyelashes and birthday-cake candles, my determination wasn't able to get the job done. Eventually, I admitted defeat, having no more success at making myself straight than if I had set out to be able to see with X-ray vision.

Times had also changed, so that it was easier to accept the fact that I'm gay without having to eschew my center-right political instincts. I had heard through the grapevine that a couple of guys I knew at Dartmouth had come out of the closet, guys I knew to be regular Joes, not the pessimistic activist types I recoiled from in college. The Log Cabin Republicans were becoming more visible, showing me that I would not have to subjugate part of my persona to be open about my sexual orientation. Being gay no longer had to be the defining feature of a person's life.

I don't know if I would have stepped out of the closet any earlier or easier had I not gone to Dartmouth and therefore not done ROTC. I definitely don't regret Dartmouth, but that choice affected me in ways I didn't anticipate when I was 17. To this day Diana is the only (straight) person who has ever asked outright if I was gay. Di, thanks for asking. I wish I could have been more honest with you and myself.

The eight years I owed the Army made for an easy excuse to ignore being gay and to stay in the closet.

JEFF DUDYCHA is a biologist at William PatersonUniversity in Wayne, New Jersey.Following his resignation, he was honorablydischarged from the Army last summer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureForged by Flame

November | December 2005 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

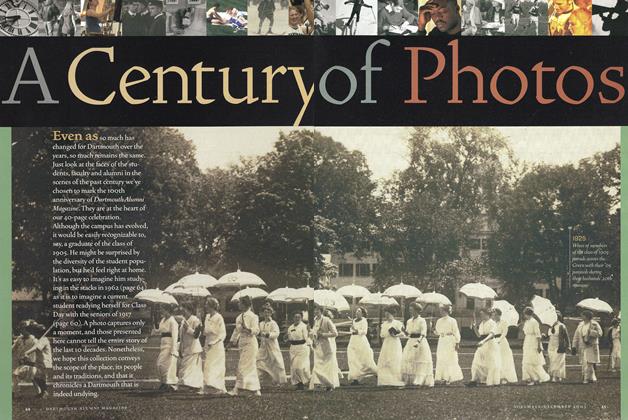

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Photos

November | December 2005 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2005 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2005 By Heather Brubaker '97, Heather Brubaker '97 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEDog Day Afternoons

November | December 2005 By LISA DENSMORE ’83 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONEggheads vs. Meatheads?

November | December 2005 By DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAM

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGoing to the Mat

Sept/Oct 2010 By Diana (Sabot) Whitney ’95 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGolden Girl

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By JUDITH GREENBERG ’88 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryLife In a Cubicle

Jan/Feb 2004 By Liam Kuhn ’02 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLife Support

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By PETER BARBER ’ 66 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYRoyal Treatment

Sept/Oct 2009 By Richard Hansen ’07 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

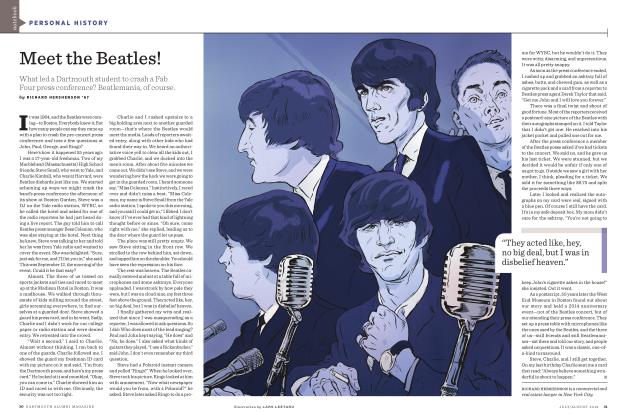

PERSONAL HISTORYMeet the Beatles!

JULY | AUGUST 2019 By RICHARD HERSHENSON ’67