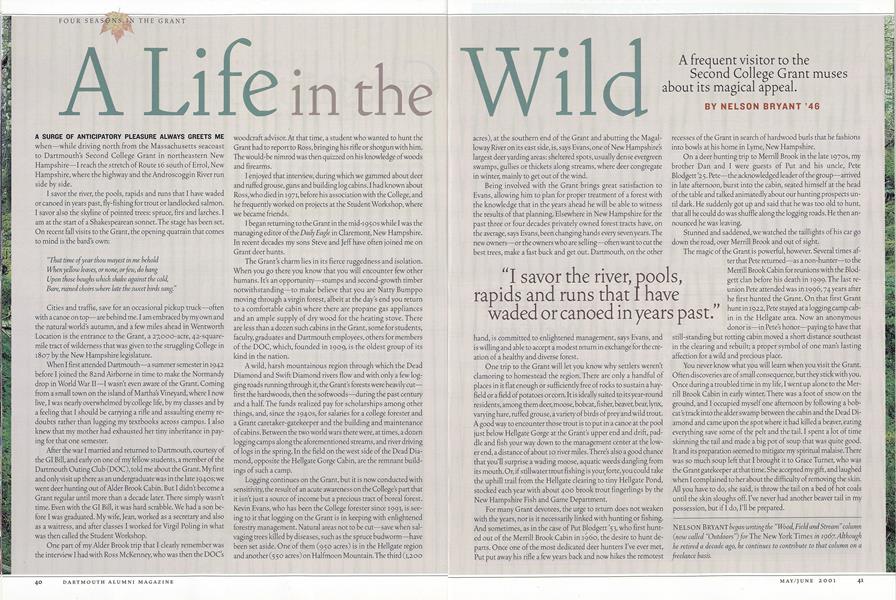

A Life in the Wild

A frequent visitor to the Second College Grant muses about its magical appeal.

May/June 2001 NELSON BRYANT ’46A frequent visitor to the Second College Grant muses about its magical appeal.

May/June 2001 NELSON BRYANT ’46A frequent visitor to the Second College Grant muses about its magical appeal.

A SURGE OF ANTICIPATORY PLEASURE ALWAYS GREETS ME when—while driving north from the Massachusetts seacoast to Dartmouth's Second College Grant in northeastern New Hampshire—I reach the stretch of Route 16 south of Errol, New Hampshire, where the highway and the Androscoggin River run side by side.

I savor the river, the pools, rapids and runs? that I have waded or canoed in years past, fly-fishing for trout or landlocked salmon. I savor also the skyline of pointed trees: spruce, firs and larches. I am at the start of a Shakespearean sonnet. The stage has been set. On recent fall visits to the Grant, the opening quatrain that comes to mind is the bards own:

"That time of year thou mayest in me beholdWhen yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hangUpon those boughs which shake against the cold,Bare, ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang"

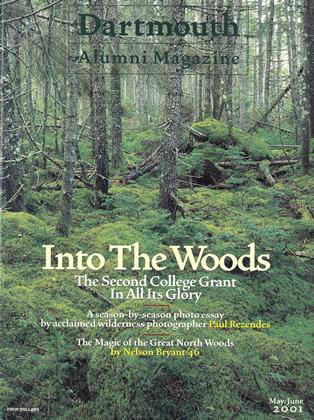

Cities and traffic, save for an occasional pickup truck—often with a canoe on top—are behind me. I am embraced by my own and the natural worlds autumn, and a few miles ahead in Wentworth Location is the entrance to the Grant, a 27,000-acre, 42-square-mile tract of wilderness that was given to the struggling College in 1807 by the New Hampshire legislature.

When I first attended Dartmouth—a summer semester in 1942 before I joined the 82nd Airborne in time to make the Normandy drop in World War II—I wasn't even aware of the Grant. Coming from a small town on the island of Marthas Vineyard, where I now live, I was nearly overwhelmed by college life, by my classes and by a feeling that I should be carrying a rifle and assaulting enemy redoubts rather than lugging my textbooks across campus. I also knew that my mother had exhausted her tiny inheritance in paying for that one semester.

After the war I married and returned to Dartmouth, courtesy of the GI Bill, and early on one of my fellow students, a member of the Dartmouth Outing Club (DOC), told me about the Grant. My first and only visit up there as an undergraduate was in the late 19405; we went deer hunting out of Alder Brook Cabin. But I didn't become a Grant regular until more than a decade later. There simply wasn't time. Even with the GI Bill, it was hard scrabble. We had a son before I was graduated. My wife, Jean, worked as a secretary and also as a waitress, and after classes I worked for Virgil Poling in what was then called the Student Workshop.

One part of my Alder Brook trip that I clearly remember was the interview I had with Ross McKenney, who was then the DOC's woodcraft advisor. At that time, a student who wanted to hunt the Grant had to report to Ross, bringing his rifle or shotgun with him. The would-be nimrod was then quizzed on his knowledge of woods and firearms.

I enjoyed that interview, during which we gammed about deer and ruffed grouse, guns and building log cabins. I had known about Ross, who died in 1971, before his association with the College, and he frequently worked on projects at the Student Workshop, where we became friends.

I began returning to the Grant in the mid-1950s while I was the managing editor of the Daily Eagle in Claremont, New Hampshire. In recent decades my sons Steve and Jeff have often joined me on Grant deer hunts.

The Grant's charm lies in its fierce ruggedness and isolation. When you go there you know that you will encounter few other humans. It's an and second-growth timber notwithstanding—to make believe that you are Natty Bumppo moving through a virgin forest, albeit at the day's end you return to a comfortable cabin where there are propane gas appliances and an ample supply of dry wood for the heating stove. There are less than a dozen such cabins in the Grant, some for students, faculty, graduates and Dartmouth employees, others for members of the DOC, which, founded in 1909, is the oldest group of its kind in the nation.

A wild, harsh mountainous region through which the Dead Diamond and Swift Diamond rivers flow and with only a few logging roads running through it, the Grants forests were heavily cutfirst the hardwoods, then the softwoods—during the past century and a half. The funds realized pay for scholarships among other things, and, since the 19405, for salaries for a college forester and a Grant caretaker-gatekeeper and the building and maintenance of cabins. Between the two world wars there were, at times, a dozen logging camps along the aforementioned streams, and river driving of logs in the spring. In the field on the west side of the Dead Diamond, opposite the Hellgate Gorge Cabin, are the remnant buildings of such a camp.

Logging continues on the Grant, but it is now conducted with sensitivity, the result of an acute awareness on the College's part that it isn't just a source of income but a precious tract of boreal forest. Kevin Evans, who has been the College forester since 1993, is seeing to it that logging on the Grant is in keeping with enlightened forestry management. Natural areas not to be cut—save when salvaging trees killed by diseases, such as the spruce budworm—have been set aside. One of them (950 acres) is in the Hellgate region and another (550 acres) on Halfmoon Mountain. The third (1,200 acres), at the southern end of the Grant and abutting the Magalloway River on its east side, is, says Evans, one of New Hampshire's largest deer yarding areas: sheltered spots, usually dense evergreen swamps, gullies or thickets along streams, where deer congregate in winter, mainly to get out of the wind.

Being involved with the Grant brings great satisfaction to Evans, allowing him to plan for proper treatment of a forest with the knowledge that in the years ahead he will be able to witness the results of that planning. Elsewhere in New Hampshire for the past three or four decades privately owned forest tracts have, on the average, says Evans, been changing hands every seven years. The new owners—or the owners who are selling—often want to cut the best trees, make a fast buck and get out. Dartmouth, on the other hand, is committed to enlightened management, says Evans, and is willing and able to accept a modest return in exchange for the creation of a healthy and diverse forest.

One trip to the Grant will let you know why settlers weren't clamoring to homestead the region. There are only a handful of places in it flat enough or sufficiently free of rocks to sustain a hayfield or a field of potatoes or corn. It is ideally suited to its year-round residents, among them deer, moose, bobcat, fisher, beaver, bear, lynx, varying hare, ruffed grouse, a variety of birds of prey and wild trout. A good way to encounter those trout is to put in a canoe at the pool just below Hellgate Gorge at the Grant's upper end and drift, paddle and fish your way down to the management center at the lower end, a distance of about 10 river miles. There's also a good chance that you'll surprise a wading moose, aquatic weeds dangling from its mouth. Or, if Stillwater trout fishing is your forte, you could take the uphill trail from the Hellgate clearing to tiny Hellgate Pond, stocked each year with about 400 brook trout fingerlings by the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department.

For many Grant devotees, the urge to return does not weaken with the years, nor is it necessarily linked with hunting or fishing. And sometimes, as in the case of Put Blodgett '53, who first hunted out of the Merrill Brook Cabin in 1960, the desire to hunt departs. Once one of the most dedicated deer hunters I've ever met, Put put away his rifle a few years back and now hikes the remotest recesses of the Grant in search of hardwood burls that he fashions into bowls at his home in Lyme, New Hampshire.

On a deer hunting trip to Merrill Brook in the late 19705, my brother Dan and I were guests of Put and his uncle, Pete Blodgett '25. Pete—the acknowledged leader of the group—arrived in late afternoon, burst into the cabin, seated himself at the head of the table and talked animatedly about our hunting prospects until dark. He suddenly got up and said that he was too old to hunt, that all he could do was shuffle along the logging roads. He then announced he was leaving.

Stunned and saddened, we watched the taillights of his car go down the road, over Merrill Brook and out of sight.

The magic of the Grant is powerful, however. Several times after that Pete returned—as a non-hunter—to the Merrill Brook Cabin for reunions with the Blodgett clan before his death in 1999. The last reunion Pete attended was in 1996,74 years after he first hunted the Grant. On that first Grant hunt in 1922, Pete stayed at a logging camp cabin in the Hellgate area. Now an anonymous donor is—in Petes honor—paying to have that still-standing but rotting cabin moved a short distance southeast in the clearing and rebuilt; a proper symbol of one man's lasting affection for a wild and precious place.

You never know what you will learn when you visit the Grant. Often discoveries are of small consequence, but they stick with you. Once during a troubled time in my life, I went up alone to the Merrill Brook Cabin in early winter. There was a foot of snow on the ground, and I occupied myself one afternoon by following a bobcat's track into the alder swamp between the cabin and the Dead Diamond and came upon the spot where it had killed a beaver, eating everything save some of the pelt and the tail. I spent a lot of time skinning the tail and made a big pot of soup that was quite good. It and its preparation seemed to mitigate my spiritual malaise. There was so much soup left that I brought it to Grace Turner, who was the Grant gatekeeper at that time. She accepted my gift, and laughed when I complained to her about the difficulty of removing the skin. All you have to do, she said, is throw the tail on a bed of hot coals until the skin sloughs off. I've never had another beaver tail in my possession, but if I do, I'll be prepared.

"I savor the river, pools, rapids and runs that I have waded or canoed in years past."

NELSON BRYANT began writing the "Wood, Field and Stream" column(now called "Outdoors") for The New York Times in 1967. Althoughhe retired a decade ago, he continues to contribute to that column on afreelance basis.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureShooting the Grant

May | June 2001 By BEN YEOMANS -

Feature

FeatureVoices in the Wilderness

May | June 2001 By Jennifer Kay '01 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GREAT NORTH WOODS

May | June 2001 By Michelle Chin '03 -

Cover Story

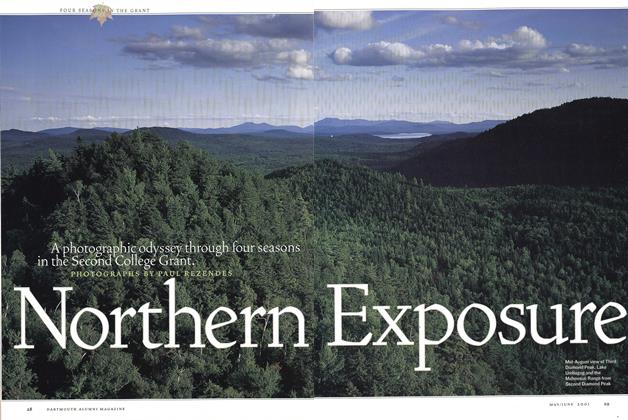

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May | June 2001 -

Sports

SportsThe Sporting Life

May | June 2001 By Lily Maclean ’01 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryThe Places You Can Go

May | June 2001 By Dustin Rubenstein ’99

NELSON BRYANT ’46

Features

-

Feature

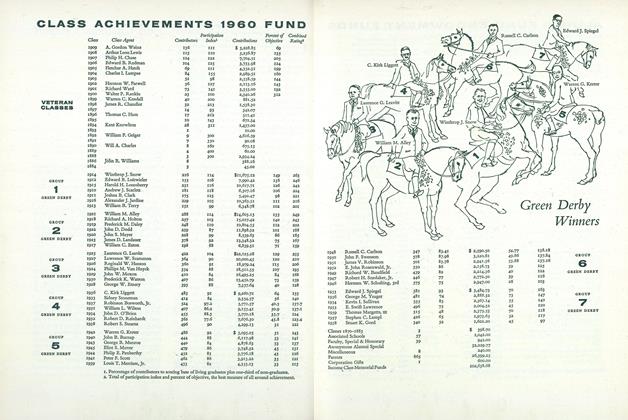

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1960 FUND

December 1960 -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Feature

FeatureFirst person

MARCH 1999 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Feature

FeatureDweck & Ivey's Good Offense

JANUARY 1998 By LINDA TITLAR -

Feature

FeatureEducation's Marshall Plan

JULY 1967 By ROBERT H. WINTERS, LL.D. -

Feature

FeatureReaching Out from Hanover

MARCH 1969 By Ron Talley '69