The Ex-Wives Club

When an alumnus and his wife split up, who gets custody of the College?

Nov/Dec 2001 Regina Barreca ’79When an alumnus and his wife split up, who gets custody of the College?

Nov/Dec 2001 Regina Barreca ’79When an alumnus and his wife split up, who gets custody of the College?

"I DON'T THINK I'LL GET MARRIED again," quipped humorist Lewis Grizzard. "I'll just find a woman I don't like and give her a house."

This line sums up how many men feel about divorce. Women, however, often have what can most politely be termed "a different set of responses."

The College talks a good game about creating the "Dartmouth Family." But what does that phrase mean when—as happens even in the best of familiessomeone files for divorce? Who gets custody of the Dartmouth experience?

It would be easy enough to say, "The person who was admitted, attended classes and graduated is the one who gets frequent visitation rights." But for years Dartmouth has accepted with gratitude (but little official recognition) the hard and enthusiastic work put forth by the wives of graduates. Without both the direct and indirect support of these women, many a fundraiser, reunion, newsletter or scholarship might have never seen the light of day.

Here is what one ex-wife of a '60 had to say in this magazines Class Notes: "In our society widows are treated kindly and solicitously, and they often remain a part of their husbands circle of friends, welcome and invited, even if their connections to the group were tenuous. Ex-wives are treated entirely differently—we are the ones who 'die' in the ex's group relationships. Yet we hold many of the same wonderful memories of time spent in Hanover and with Dartmouth friends. We're still part of the clan. I would venture a guess that there are probably more second and third wives in the class of 1960 than there are first and only wives; one more sad statistic of our silent generation.' I know many ex-wives of the class of 1960 for whom the shock of being summarily removed from the group (to put it gently) was a real source of sadness and hurt. All I ask is that you think as kindly of us ex-wives as you do the widows, even though that is rather counter to our cultural norms. Our feelings for Dartmouth may well run just as true and deep as any. We bore their children and shared their lives. To be obliterated without the slightest trace is an insult and cruel. We deserve better."

One evening last year, after delivering a lecture in New Jersey, where I mentioned in passing my undergraduate years, I met a woman who introduced herself to me as an "ex-wife of Dartmouth." Married to an alum, but now divorced, she sounded as frustrated by the College as she was by her former husband. "Does anybody reach out to make me feel part of the gang' since he remarried? The only people I've heard from are other ex-wives—apart from a couple of his more disreputable friends, who wanted to hit on me. What burns me up is that most of them accept his new wife without question and make her feel as much a part of the whole Dartmouth exPerience as I did."

I reached out. Maybe not the way she expected or hoped—not, in other words, to offer tea and sympathy—but in a way that nevertheless prompted several long discussions, as well as many martinis.

Because I come at the experience from a wholly different angle—having originally made what my best friend refers to as "that all-important first marriage" to a decidedly non-Dartmouth type—this ex-wife put me in touch with other women who had stories similar to her own. I should note that, in contrast, not one alumna to whom I've spoken faced any expressions of desire on behalf of her non-Dartmouth ex-husband to remain part of the College community once the marital tie was irrevocably frayed. Perhaps this can be explained by a sense of connection the ex-husbands have to their own home institutions or by the fact that they themselves were not emotionally invested in their wives' earlier commitments. Or maybe they just never looked good in green. My own ex had little time for Hanover when he was married to me, and as far I can tell, no interest whatsoever in ever seeing New Hampshire again once the marriage ended.

What I discovered about Dartmouth's ex-wives, however, surprised and impressed me. The Dartmouth ex-wife does indeed see herself as a part of the community. And I think we should take a look at her.

Picture Barb, Linda, Ellen, Cathy, Liz or Sue. She's attractive, sophisticated, educated and about the same age as her exhusband. They met when she was at Colby-Sawyer Junior College, Smith, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, Wheaton or Pine Manor. A big part of their time together involved Hanover; it always had. From the start, she spent more time in his frat house than he did at her place. She always knew the names of his best friends and, over the years, became close to their wives. Dartmouth was part of his life, and she, in turn, considered the College to be part of hers.

She attended fundraisers, gave galas and worked harder for his alumni events than for her own alumnae association. They both agreed that financial support for college was an important part of their charitable giving. Somehow it seemed more appropriate for him to give to his college than for her to give to her own. After all, he made the income—even if she was a crucial part of the process. Parties and picnics, graduations and games—all of these were awarded room in her heart. She never had a sense of being an outsider, an interloper or in any way superfluous. She was a vital part of the Dartmouth Family.

And then the marriage was over. What did these women say, when asked about their feelings about their exhusbands, the College and their new lives?

"I miss what we once had. I still remember the first time he kissed me. It was in 1963, during Winter Carnival."

"I still stay at the Yale Club in New York when I'm in the city."

"I still believe I have every right to participate in those events that have been part of my last 20 years."

"I make a donation to his class fund in his name every year, and they apparently keep sending the thank-you letters to his new house. So his new wife opens them. It's a small act of revenge, but it pleases me."

"I've learned to attend College and alumni events on my own without making an apology. People ask me, 'How are you connected to the class?' For the first year could barely hold back the tears. Then I came up with the right line. I now answer, 'So-and-so is, I regret to announce, my exhusband.' That way I leave them to figure out if my regret is the fact that we're not married now—or that we ever were."

"I always went to every reunion, no matter how tough times were. You have to go to the college reunion. If you don't, they'll think you're unhappily married. And it's when you're unhappily married that you really don't want anyone to guess! Mostly I miss the parties and the old friends who obviously feel they can't call without offending my ex. I'd love to be invited back but don't feel as if I can just barge in and say'Hi, y all!'"

What's behind us shouldn't control our futures, but continuity, even in the face of life's monumental changes, remains important. Often the most effective ways to transform how we reflect on past experiences is by inventing new ones, not to replace the burden of memories but to lighten it.

A raucously funny former wife of an alum proposed a solution: an annual reunion of all Dartmouth ex-wives ("or ex-husbands, I suppose," she added thoughtfully). "We should take over all of Hanover for one weekend. Forget the railroad ties: We could build a bonfire constructed of old love letters, clippings and pictures. We could celebrate our new lives while kidding about and remembering the old ones."

A different kind of homecoming, perhaps, but who ever said that families can't make adjustments?

REGINA BARRECA, an author and Englishprofessor at the University ofConnecticut, is editing The Penguin Book of Italian American Writing (a.k.a. Don't Tell Mama), due out next year

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

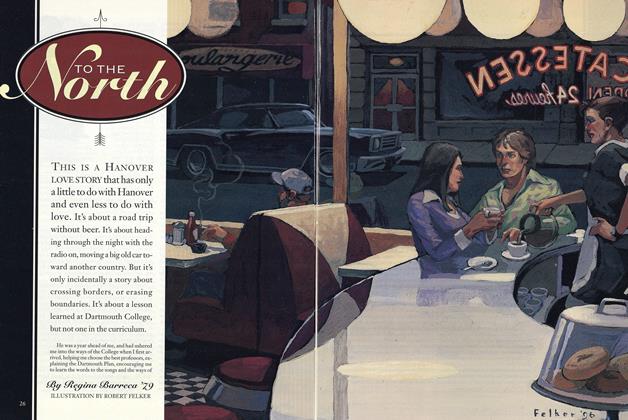

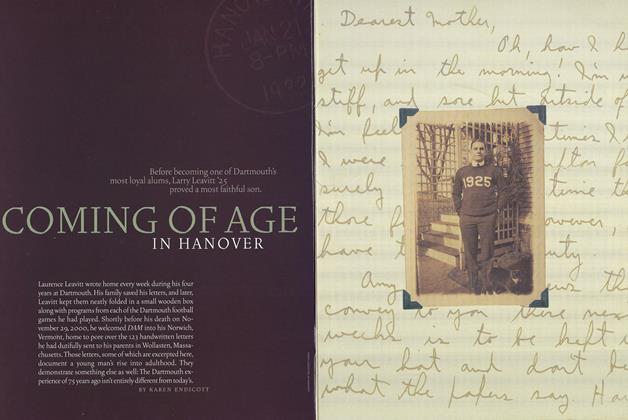

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

November | December 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHow Does Our Garden Grow?

November | December 2001 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Big Picture

Big PictureSeptember 11, 2001

November | December 2001 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2001 -

Classroom

ClassroomIs There a Robot In the House?

November | December 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

November | December 2001 By Nihad M. Farooq

Regina Barreca ’79

Alumni Opinion

-

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONJustice—and Politics—For All

Nov - Dec By Ernest A. Young ’90 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionDeclaration of Independence

July/August 2012 By John Fanestil ’83 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionLost in Cyberspace?

Jan/Feb 2001 By Mark Pruner ’77 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONWinning Without Weapons

Nov/Dec 2007 By Nathaniel Fick ’99 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionGoing Nuclear

Mar/Apr 2010 By Scott S. Brown ’78 -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONReturn of the Critic

May/June 2010 By William Morgan ’66