How Does Our Garden Grow?

An inside look at how Dartmouth manages its money—in difficult times.

Nov/Dec 2001 JAMIE HELLER ’89An inside look at how Dartmouth manages its money—in difficult times.

Nov/Dec 2001 JAMIE HELLER ’89THE COLLEGE'S $2.4 BILLION ENDOWMENT PROSPERED WITH THE BOOM ECONOMY. BUT LAST YEAR SAW THE FIRST NEGATIVE RETURNS IN MORE THAN A DECADE. AN INSIDE LOOK AT HOW DARTMOUTH MANAGES ITS MONEY—IN DIFFICULT TIMES.

For most small investors, eToys epitomized all that was wrong with the Net craze of the 19905. A smashing IPO and massive marketing campaign quickly spiraled into layoffs, bankruptcy and a worthless stock.

But for Dartmouth College, the short-lived online toyseller was a winner. An early investment of just under $200,000 in the company brought the College a return of about $5 million—cash. Dartmouth College a Net stock speculator? It's a strange image to conjure at an institution anchored by enduring edifices, undying traditions and a never-fading Green. But Dartmouth's prosperity is closely tied to the stock market. And for a long time, that was a good thing.

Thanks in part to windfall venture capital investments such as eToys, Dartmouth has one of the biggest and best-performing endowments in the Ivy League. In the last nine years it has grown from less than $744 million to $2.4 billion. In the thick of the bull market in early 1998, the board of trustees decided to spend more out of this institutional kitty than it ever had before, making the endowment an increasingly crucial revenue source at the College. The change seemed innocuous enough: The College had the dough, so why not put more to use now rather than hoard it all for future generations? In retrospect, however, the spending hike, and a subsequent one approved in spring 2000, reflected buy-at-the- top" timing: The stock market went south shortly after the trustees loosened the purse strings. Just as the College became more reliant on the endowment for its operations, the giddy times that fueled the endowment turned grim.

"That's an irony," says College treasurer Edwin Johnson '67. Ironic, and potentially troublesome. It's a precarious time at Dartmouth, as it is for other private schools that made aggressive investments and got accustomed to endowment-fueled budgets. Moody's Investors Service, the credit rating firm, in July 2001 wrote that if "negative returns in financial market results persist, operating spending by colleges and universities will eventually have to be scaled back." The report praised the "wisdom" of schools that resisted rapid spending hikes even as their endowments billowed.

But Dartmouth was not so restrained. It earned more, and it spent more. And why not? There was plenty of money for everyone. Now that the trend has turned—fiscal 2001 saw the endowment s first negative returns in a decade—difficult choices face the keepers of Dartmouths endowment, from asset allocation to spending formulas.

"It's not widely appreciated, but the ability of the College to do things is very dependent on what's happening in the financial world," says Peter Fahey'68, chair of the trustees' investment committee and a retired Goldman Sachs partner. "We have to look forward at an array of possible outcomes in the financial world and our operational ambitions and make judgments about what the likely financial outcomes will and will not permit us to do. If things are good we can put our foot to the accelerator and be aggressive and do things we want to do." But if the market continues to suffer, he adds, "some of the plans will have to be slowed down."

As a war on terrorism grips the nation and the economy sputters, as the stock market faces uncertainty and recessionary woes threaten to increase students financial aid needs, trustees and ad ministrators will have to wrestle with how much of a potentially shrinking endowment to preserve for future generations, and how much to spend today. When there is less, the question becomes much tougher: Dollar for dollar, who is Dartmouth's endowment for?

As fiscal 2002 began on July I, the endowment stood at $2.4 billion. The Colleges expenditures for the past year were $426 million. Theoretically, the endowment alone—without tuition, grants or other revenue sources—could easily cover the costs of running the College for about five years (not counting inflation). Theoretically, because the endowment actually could never be spent that way.

While the endowment is often thought of as one big cookie jar that the College can stick its hand into whenever it wants a nosh, in fact it's neither a single jar, nor is it open to the taking.

The Dartmouth "endowment" comprises nearly 5,000 endowment "funds," which generally begin as separate donations to the College for specific purposes. There are funds dedicated for scholarships, faculty chairs, the Hood Museum, the Hop, the Tucker Foundation, maintenance of the golf course, books about the South during the Civil War, firewood in the presidents office. About 72 percent of all endowment funds are restricted in terms of their spending purpose, though almost all are pooled together for investing.

Donations to most endowment funds don't actually get spent. The concept of an endowment is that the donated gift dollars are maintained "in perpetuity" for the good of future generations. Take, for example, a gift of $10,000. If that's made to the Alumni Fundwhich is not part of the endowment—the College can spend it right away. But if it were a typical endowment gift, the College could spend only interest or appreciation it earns on that money; the $10,000 principal can't be touched. (It can, however, be lost through declining markets.)

This two-track giving structure—current vs. future gifts—creates a clash of interests between todays students and tomorrows. A dollar donated to "current use," i.e. the Alumni Fund (a.k.a. the Dartmouth College Fund), is a dollar that doesn't make it into the endowment. A dollar into the endowment is a dollar that doesn't directly benefit the current student body.

The tension between these two camps surfaces not only in the donation process, but also with endowment investing and spending. A conservative, low-risk investment approach helps ensure predictable returns that a budget bean counter can depend on in shortterm forecasting. Aggressive investing could create more volatility in the short term in exchange for bigger gains down the line. On the spending side of the ledger, a choice to use gains today means they're forever gone from the endowment. Adecision to reinvest gains is a vote to preserve capital for later use.

For much of the 19905, Dartmouth made some aggressive investments and kept to a lock-step spending formula. Between the two approaches, plus ample gifts in a bullish market, the endowment grew steadily, winning not only accolades at home but high marks among competitor institutions.

Among the nations private colleges and universities with the largest endowments, Dartmouth ranked No. 16 for fiscal 2000. Within that top-20 pool, Dartmouth ranked even higher—No. 8— on a dollar-per-student basis, at $473,096, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

As for investment returns, Dartmouth boasts the best one-, three- and five-year performances among the Ivies through June 30, 2000. From 1993 through 2000, it saw double-digit returns every year except 1994, which was a bad year for the market overall. And while comparative figures for fiscal 2001 were not available for this article, Dartmouth did well against broader market benchmarks, losing only 0.4 percent, while the S&P 500 dropped nearly 15 percent in the same period.

The investing success is largely due to venture capital—investing in private companies that are expected to reap huge valuations if they are bought or become publicly traded. Dartmouth made its first venture capital fund investment back in 1978, and followed with many more over the years. So when this asset class saw wild success in the late 19905, Dartmouth was ready to profit. Essentially, hundreds of millions poured in.

To hear endowment manager Jonathon King describe the period, it sounds like the early-era E*Trade commercial where the truck driver cum online-trader buys himself an island. King, the associate vice president for investments, and his staff of three in Hanover don't pick stocks, they pick money-management firms with various specializations, which in turn purchase individual securities. These managers had Dartmouth invested in companies that turned into some of the hottest initial public offerings of the decade, including As Ask Jeeves Phone.com, Sycamore Networks and Yahoo!

"We used to sit around the Bloomberg [data terminal] on a Friday afternoon looking at how many millions we made in IPOs," says King. "You could be up $15 to $30 million on a good week. We knew it was craziness, and now in hindsight it was."

As these private companies became publicly traded, venture funds would turn over to Dartmouth its share of the newly minted securities. The College then had a choice: hold or sell. And fortunately, it sold a good deal, though not all. For fiscal 2000, the endowment raised about $243 million in cash from selling proceeds from venture capital investments—a whopping 10 percent of the endowment.

Why sell? First, there was an inkling that these mostly speculative stocks were overvalued, and it was wise to cash in. Selling "was almost common sense, as the distributions were coming at us at huge valuations," says King.

Yet King also sold because he had a certain asset allocation to maintain. The "private equity" portion of the portfolio, mostly venture capital, was only supposed to constitute 18 percent of the entire portfolio. But even after receiving and selling hundreds of millions of distributed stock, the Colleges remaining venture capital investments constituted about 23 percent of the endowment in June 2000—way over target.

Indeed, with returns so enormous, the trustees, in a very rare move, had altered the endowments asset allocation to increase the portfolios target for private equity, raising it from 15 to 18 percent in February 2000. "At that point the portfolio was going through the roof," says King. The College "didn't want to be totally on the sidelines" and not be able to make additional venture capital investments, he adds.

In hindsight, the adjustment was in one respect too little, and in another, too late. With the portfolios wild returns leaving the 18 percent target in the dust, the change was really a losing game of catchup for fiscal 2000. As for subsequent years? Just one month after the upward adjustment, the tech-laden Nasdaq stock market hit its all-time highs and started to tumble. Venture-capital investing has been suffering ever since.

Still, hindsight is just that. Back in the late 19905, with strapping returns the norm, the trustees reevaluated the Colleges spending policies. "You don't want to just squirrel away for the future, you want to spend some now to continue to stay at the top of the higher-education hierarchy," says Susan Dentzer '77, now chair of the board of trustees.

The approach the trustees had been using aimed to keep the endowment's contribution to the annual budget steady. Each year saw a little more spending than the prior year to cover inflation and add a dash for real growth.

Here's how it worked: The trustees would take the amount spent the prior year and increase it by a set percentage, around 5 percent, to come up with the spending figure for the current year. Then, to make sure that this figure wasn't too high (overly generous to current students) or too low (overly generous to future students), they compared it to the actual average market value of the endowment over the prior three years. If the figure was between 4.25 and 6.5 percent of that average market value, it was considered fine. If it approached 4.25 percent, that suggested the College might not be spending enough of a growing endowment. If the endowment had shrunk, the figure would start approaching the 6.5 percent ceiling, indicating that the school was spending too much.

The difference between 4.25 and 6.5 percent might not seem like a lot. But on a $2.5 billion endowment (its value in fiscal 2000) it would be the difference between spending $106 million and $162.5 million. That's nearly the price of the Baker-Berry Library project, pegged at $64 million.

With the bull market of the late 19905, the auto-increase approach meant that a smaller and smaller percentage of the growing endowment was getting spent. In other words, the College was coasting near the 4.25 percent floor; future generations were being favored over current students. So for fiscal 1999, the trustees altered course. Rather than just build on the 1998 figure, they decided to spend 5.25 percent of the endowment's average market value during three years, even though that meant a 41 percent increase in spending over the prior year, translating into a $19.8 million hike.

"The model hadn't been working by leaving it on autopilot," says Johnson. The trustees decided "we're going to be active about fine tuning it," he adds.

For the fiscal 2001 budget, decided upon in the spring of 2000—when things still looked fairly rosy—the trustees upped the figure again, to 5.5 percent of the three-year average market value. That created a 37 percent increase over the prior year's endowment distribution, which amounted to a $31.8 million hike.

The upshot: Spending out of the endowment more than doubled from 1988 to 2001, to more than $100 million.

The increases meant that 29.7 percent of 2001 revenues for the undergraduate College came from endowment funds and other investment income, compared to only 19.0 percent in 1996. With the extra cash, the College did things like bolster its financial-aid budget, build psychology center Moore Hall, finish renovations in the science buildings and fund parts of the student life initiative. For fiscal 2002, endowment and other investment income is expected to count for 31.6 percent of total revenue for the undergraduate College.

But just as the College had gotten used to a generous injection from the endowment into its current revenue pool, the stock market soured, and with it, the endowment's glowing returns.

The private equity/venture capital portion of Dartmouth's portfolio, once yielding triple-digit returns, lost more than 20 percent for fiscal 2001. The year wasn't a total disaster. The portions of the portfolio in bonds, hedge funds (meant to perform well in up or down markets) and real estate all did well. So while the endowment had its worst year in a decade, it minimized its losses with these other investments, losing 0.4 percent, or $6.6 million.

That small decline won't make a big dent. But if times get worse, the endowment could shrink, not only because of weak returns, but because history shows that giving falls off with bad stock markets.

The prospect has administrators rethinking the status quo. Johnson, calling Dartmouth "pretty heavily reliant on venture capital," asks, "Do we need to make fundamental adjustments in our asset allocation going forward?"

Fahey doesn't anticipate swift changes. "We're long-term investors and we know that in the long run private equity should on a long-term basis have higher returns than any of the other asset classes that we invest in." He adds that because venture investing often requires 10-year commitments, it's hard to change posture quickly.

It all sounds sensible enough for those future students who will enroll years from now. But what about today's students and faculty, whose budgets depend on the endowment as it exists? Venture capital performance is tied to the broader domestic stock market, which itself is a hefty part of the portfolio—about 30 percent. A bad stock market and crumbling economy could mean a decrease in the endowment's contribution to the annual budget at the same time that tuition revenues could decline if fewer can afford to pay the full fare.

Fahey maintains that if the broader equity market can get back to 9 to 10 percent annual returns, "we can do fine with the current asset allocation and spending formula. But, he says, if markets return 5 or 6 percent or worse, "that's going to be very constraining to what we can do; then we're not in a position to do anything more than just stay even." And what does he think a sustained downturn would bring? "An unhappy environment at Dartmouth and the university community generally."

Therein lies perhaps the biggest paradox: What's an endowment for, if not to help an institution through bad times? In a crunch, why not tweak the spending formula to draw down extra cash?

The endowment keepers wriggle at the suggestion, because the more spent now means less for later. But when is later? It's the kind of questison a family might face when a breadwinner loses a job. If suddenly there's less income, does the family trim its budget or dip into the emergency fund?

Dartmouth's approach historically has been to pull in its horns" on the budget side rather than tap the kitty, says Dentzer, though she says it's too soon to say how Dartmouth would react to a long-term bear market.

Johnson echoes a similar sentiment, saying any rainy-day use of the endowment is meant for dire situations. We're talking earthquakes. Metaphorically and literally. The College rests on a geographical "fault line," he's been told. That's the type of crisis the endowment is for, he says.

Perhaps Johnson is onto something—perhaps those buildings surrounding the Green are not as stable as they seem. Since the September terrorist attacks, little is.

JAMIE HELLERK a freelance writer living in New York City.

"You don't want to just squirrel away for the future, you want to spend some now to stay „ at the top of the higher-education hierarchy. -TRUSTEE CHAIR SUSAN DENTZER '77

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

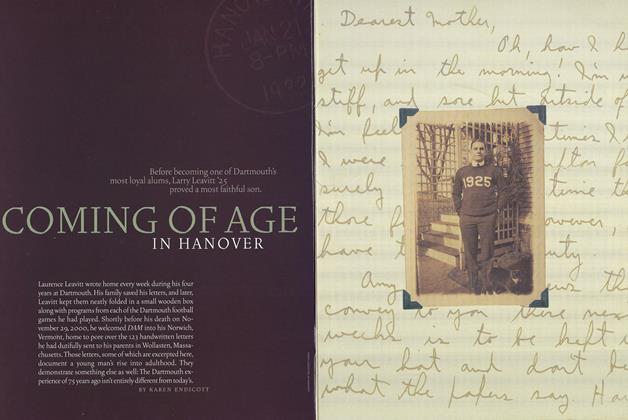

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

November | December 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Big Picture

Big PictureSeptember 11, 2001

November | December 2001 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionThe Ex-Wives Club

November | December 2001 By Regina Barreca ’79 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

November | December 2001 -

Classroom

ClassroomIs There a Robot In the House?

November | December 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

November | December 2001 By Nihad M. Farooq