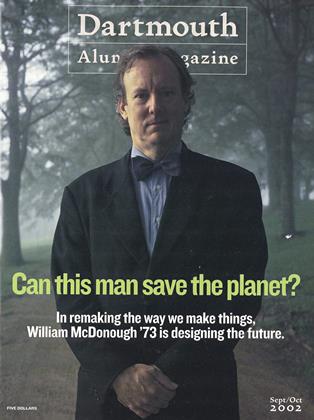

Designing the Future

Environmental architect William McDonough ’73 sees a world of abundance, not one of limits, pollution and waste. It’s a visionary idea—and a burgeoning reality.

Sept/Oct 2002 Brian DumaineEnvironmental architect William McDonough ’73 sees a world of abundance, not one of limits, pollution and waste. It’s a visionary idea—and a burgeoning reality.

Sept/Oct 2002 Brian DumaineEnvironmental architect William McDonough '73 sees a world ofabundance, not one of limits, pollution and waste.It's a visionary idea—and a burgeoning reality.

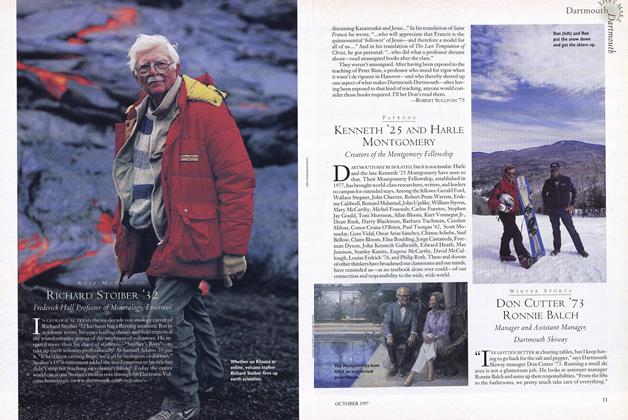

Bill McDonough has one of the toughest jobs in the country. He sells green ideas to hardened, skeptical executives. A couple of years ago McDonough, who runs a small architecture firm in Charlottesville, Virginia, was telling a Ford manager that he wanted to put skylights in the roof of the company's River Rouge car plant in Dearborn, Michigan. The manager, having had years of experience with leaky skylights, snapped back, "I know all about architects like you. You want to come in and put pretty skylights in factories. Do you what we do with skylights at River Rouge? We tar them over."

That's just the kind of challenge McDonough loves. He drove the manager to a nearby Herman Miller plant he had designed and went into his green sales rap. This smooth-talking, bow-tied Ivy Leaguer rattled off the advantages of his green designs. The Herman Miller plant lets in lots of natural light and fresh lair, the skylights are vertical so they don't leak, and oh, by the way, productivity has increased so much that the Herman Miller factory helps pay for itself. Sold.

This was just another minor skirmish in what, to McDonough's mind, is a much bigger war—to win over the business community to a new way of thinking about environmentalism. It won't be easy, because McDonough is no ordinary green crusader. His message: Todays environmental movement, though well-intentioned, is in many ways flawed. And this dapper dresser, who looks a lot like the actor Michael Keaton, isn't at all shy about telling you why.

His philosophy in a nutshell: The current green movement is about efficiency and about reducing the amount of toxins that go into our air, water and earth. A noble cause, but, as McDonough argues, this approach does nothing more than slow the rate at which we're poisoning ourselves. Says he: "How can something be good if it makes you sick? How can it be good if it destroys the planet? How can it be good if it causes global warming? Is that good design?"

Instead, McDonough proposes a world in which solar and wind energy replace nuclear and fossil fuels, in which natural light and air replace air conditioning, in which safe ingredients replace toxic chemicals in our clothes, homes, offices and factories. But his world is not one of scarcity, not one of a Jimmy Carter, put-on-your-cardigan, turn-down-the-thermostat kind of malaise.

McDonough celebrates abundance. He believes in passive-energy systems that will let you take the longest hot-water shower you could ever want, factories that can grow without polluting the environment, and goods that, when thrown away, become food for other living things or can be cheaply and easily recycled into high-quality products. Here's McDonough on a roll:

Growth is good; ask a tree. A kid grows; that's good. So the argument in commerce aboutgrowth and no growth is a stupid argument. Of course you have to grow; nature wants youto grow and businesses want to grow, but if businesses have to grow and environmentalistscome along and say your growth is ruining the earth, that's because the growth is not following nature's laws. But what if growth were good? What if that factory purifies waterand makes oxygen? That's interesting. And different from "I want less bad versions of whatwe already have."

Sound Utopian? Yes. And at times one is tempted to roll one's eyes at McDonough's unbounded, tree-hugging optimism. Also, carried away by his own enthusiasm, he may at times exaggerate the benefits or practicality of his green philosophy. That said, there's no doubt that he's a supersalesman for the movement. "Bill is the Johnny Appleseed of ecological architecture," says David Orr, the head of environmental studies at Oberlin College and someone who has worked with McDonough.

As McDonough sprinkles his ideas around, some very powerful people in the business world have started to follow his lead. Ford Motor CEO William Ford Jr. has hired Mc-Donough to be chief architect for a 10-year, $2 billion redesign of the River Rouge car factory. Ford wants to turn this grimy plant into an environmental showplace. As the deal was signed, Bill Ford hailed McDonough as one of the most "profound environmental thinkers in the world." A few years before that, McDonough persuaded the chairman of Gap to put a grass roof on his San Bruno, California, office complex. A grass roof? The grass, argued McDonough, is good for drainage, doesn't need maintenance and provides UV insulation, and the birds love it too. Phil Knight of Nike hired him to develop running shoes whose soles, when discarded, become food the list goes on.

Will more of the business community sign on to McDonough's vision? The World Trade Center tragedy makes it all the more likely As long as America remains dependent on Middle East oil, it will need to be embroiled in the politics of that region. As Princeton economics professor and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman writes, "If that dependence is ever to end...we'll have to find a way, through some combination of technological innovation and radical politics, to wean not just the United States but the world economy as a whole from its dependence on oil."

And then there are the selfish reasons to become a believer. McDonough has shown that—whether you're a Fortune 500 company or a small business—his green buildings can boost productivity and reduce costs. In addition, the green movement will provide huge opportunities for entrepreneurs eager to start new businesses ranging from solar design, recycling and fuel cells to green construction and landscaping. Says Tim O'Brien, director of Fords Environmental Quality Office: "This is just the dawn of opportunity for entrepreneurs."

William McDonough + Partners is a 40-person architecture firm located in an old vegetable warehouse in Charlottesville. Founded in 1981, the firm has designed buildings for Gap, Nike and Oberlin College. McDonough, who was dean of the architecture school at the University of Virginia from 1994 to 1999, was looking to broaden his green campaign beyond architecture. He hooked up with chemist Michael Braungart, who runs an environmental firm in Germany. Today their two firms cross-fertilize each other: Braungart provides expertise in chemistry and McDonough in design. For instance, working in collaboration, the firms designed environmentally friendly textiles. Making cloth can be a very dirty business, so McDonough and Braungart helped a Swiss company, Rohner Textil, sift through 1,600 chemical dyes before finding 16 that were nontoxic. The company now uses safe dyes for textiles. When Swiss regulators came to measure the outflow from Rohner's textile mill, they at first thought their instruments were broken. The water flowing out of the mill was as clean as drinking water.

McDonough's unbounded enthusiasm for things green started when his father, the Far East representative for Seagram, moved the family to Hong Kong in the mid-19505. There, the 6-year-old McDonough had his first run-in with scarcity. Hong Kong was so densely populated that during the dry season his family had to get by with only four gallons of water every four days. Says McDonough: "That's when you really see what happens when you overload the system."

After getting his undergraduate degree in 1973 from Dartmouth, where he developed a passion for photography, McDonough signed on as a junior member of a team entering a contest sponsored by King Hussein of Jordan to create a 100-year housing plan for the Jordan River valley. McDonough's team won by suggesting that the Jordanians design housing based on ancient Bedouin principles. While a Russian team proposed littering the valley with Soviet-style housing blocks, McDonough's team suggested adobe houses that could take advantage of indigenous materials and provide cool shelter from the burning desert.

According to McDonough, if the homes were built of mud, the local people could build and repair them themselves. The huts also have domed roofs so they don't need any tensile structures. In other words, they don't need any trees or steel, which would be expensive and require shipment into the desert. Today the Jordan Valley is littered with adobe huts.

The experience in Jordan became the foundation for McDonoughs entire philosophy. But let him tell it.

In Jordan I was sitting in a Bedouin tent, and instead of saying, "Oh,my God, I've gone back centuries to some primitive ways," I saw it as one ofthe most elegant structures I've ever seen. You've got your factory—goats-following you around and eating what you can't eat and making hair out ofthat for you. At the same time it gives you meat, milk and entertainment. Andthen rejuvenates the soil with its droppings—a full cycle. So it's a solarenergy transformation.

So you take solar income and turn it into goat hair, and turn that into avery rough weave. Now you're in 120-degree heat and there's no wind, there'sno shade. And guess what? You're sitting in the tent and saying, "Hey, I'msitting in deep shade, and the temperature is 95 degrees; that's interesting."And the design of the tent through convection creates a breeze. Now you'rein a cool breeze, and the lighting is exquisite because the tent lets in a thousand pins of light. It's magnificent.

So we're going to solve the energy problem because we have income, solar income. But we're notgoing to solve the mass [fossilfuel]problem becausewe don't have mass income—the occasional meteorite? The mass of the earthis getting toxified, the soil is getting depleted, and we're cutting down ramforestsand losing genetic information. The energy is not the problem, it's the mass.We'll figure out energy because we have the solar income. You can do it.

When his experience in Jordan ended, McDonough enrolled in Yale's architecture school, where he picked up enough knowledge to design the first solar house in Ireland. Then, in 1977, he went to New York City, where he apprenticed for four years at a big firm, Davis Brody, before starting out on his own. His big break came in 1984 when the Environmental Defense Fund asked him to design its headquarters in New York City. This building, which ended up having a lot of light, greenery and fresh air, was the first commercial project to address the "sick-building syndrome" head-on. For instance, McDonough improved air quality by using non-toxic building materials for finishes, paints and even adhesive for the carpets. A lot of what McDonough does is plain common sense:

A while back a newspaper did a piece on me, and the headline was "TheLatest-Innovation in Office Buildings: Windows that Open." I called the reporter up and said this was a low point in Western civilization. Architectssay you can't make skyscrapers with windows that open. Of course you can.The Empire State Building has them. People have just forgotten how to do it.

After the Environmental Defense Fund project, McDonough worked on a number of small but high-profile projects like the lavish Paul Stuart clothing store on Madison Avenue in New York City, in which all the oak in the suit room comes from replanted American forests. Then, in 1998, Gap chairman Don Fisher hired him to design the company's corporate campus in San Bruno because he liked McDonough's concept of "an undulating meadow of ancient grasses." Today the roof of the San Bruno building has grass and wildflowers growing on it. The interior, lit by walls of glass and decorated with swaths of indoor plants, in many ways resembles an undulating meadow The place is also 30 percent more energy efficient than state law requires. Listen to McDonough's words: With the Gap building, we used raised floors through the whole building so we can take the nighttime air, let it flow under the raised floor and let itcool down the building all night like a tent in Jordan or a hacienda. No one hasever done that in a whole building; it has allowed us to cut back on energyuse. Pacific Gas & Electric gave us an award as one of the most energyefficient buildings in California, and we weren't trying to be efficient—we weretrying to be effective. And we did this without minimizing the amount of daylight or fresh air in order to minimize the air conditioning. This is what traditional energy-efficient buildings try to do. But you end up living in the darkwith bad air.

Yes, being green is nice, but what's in it for the shareholders? Plenty, if you happen to own stock in Herman Miller. In 1996 McDonough designed a factory and showroom for the office furniture maker in Holland, Michigan, that is energy intelligent and bathed in natural light and fresh air. According to Judith Heerwagen, a Seattle-based environmental psychologist, the improved working conditions boosted productivity and strengthened morale. Herman Miller says that it not only saves about $35,000 a year on electrical costs but also benefits from reduced turnover and absenteeism.

Ford, too, is saving a lot of green by being green. McDonough's revamping of its i,loo-acre River Rouge production site, where Henry Ford started making his Model T's 85 years ago, isn't just some philanthropic project; it has to make financial sense. Consider the 1-million-square-foot assembly plant that's under construction, where Ford plans to make F-150 trucks. Originally the company was going to build a traditional (and expensive) water drainage and purification system to keep pollutants from being washed into the river during rainstorms. But McDonough had a better idea: Why not let nature do the work, and save money along the way?

As McDonough explains:

Most factories are designed today so that if you get a 1-inch rainfall, ithits the roof and rushes down the gutters into big pipes and into the river asfast as possible. The runoff picks up all the particulates that may have droppedon the site—everything in the soil, the detritus, the harmful chemicals. Wouldn'tit be interesting if we could make the water travel from the building tothe river in three days rather than three minutes? Then you avoid floodingand the dangerous water. Then we said, "What if we used the grass roof ofthe Ford assembly plant to absorb water and make oxygen." The water thatdoes run off falls onto a porous paving in the parking lot, so the water isabsorbed, and it's filtered through wetlands with native habitat on the wayback to the river.

Here's what's exciting to the shareholders at Ford. We priced this out at $13million. If Ford had used conventional engineering, it would have cost the company $48 million to build a chemical-treatment facility because the system wouldhave to handle millions of gallons a minute. And the regulators loved this newsystem because there was nothing to regulate. You have to regulate what comesout at the end. What comes out here? A trickle that's clean.

When you hear McDonough espouse his green ideas, many of them seem so simple and so economical it makes one wonder why they're not being adopted more quickly. The answer is that the ideas are radical, and most people need to be educated—if not dragged kicking and screaming—before they're willing to accept anything new.

Just ask David Orr, Oberlin's head of environmental studies, who hired McDonough to design the Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies. The just-completed building is one of the most advanced green buildings in the country. Its graceful curved roof has 17,000 square feet of photovoltaic cells to generate electricity, and the building has geothermal wells for heat. The interior, bathed in warm natural light, uses wood only from replanted forests, and the grounds consist of native plants so no harmful pesticides or fertilizers need be used. The building even has a "living machine" made of plants that cleans and recycles all its wastewater.

However, Orr says that the $7.5 million project, which he considers a success, was much harder to pull off than it should have been. "Green design isn't taking regular architecture and doing cute add-ons. It's a whole different thing. You're trying to see the building as a system where everything has to work together. And institutions and businesses are not set up yet to handle the transition." For instance, because of some of the misunderstandings between McDonough's firm and the local engineers, the geothermal wells are not yet connected, and an energy-hungry electric heater and fan was installed to provide warmth in winter. Not very green.

And some people at Oberlin aren't making it easy for Orr to go forward with his green projects. One faculty member made it his mission to denounce the building. Why? Forone, McDonough seems to have overpromised. He sold the building as a net generator of energy. In other words, it would, thanks to the geothermal wells and phovoltaics, generate more power than it consumed. So far that has not been the case.

It will take time and a lot of education before McDonough's vision of the world becomes more widely accepted. That doesn't seem to bother him. His small firm has more work that it can handle. And for those people who are too stubborn to see the world McDonough's way? He calls them mules. "We don't really worry about them," he says. "They'll only be around for one generation, because, like mules, they're sterile."

the fine art of changing the world

There are some people who change the world, and they make the rest of us uncomfortable as hell. They speak the language of outrage, confronting us with our falsehoods and failings. They are relentlessly focused. They self-promote. They are fanatical—and since fanatics truly bug us, we mostly dismiss them as flakes 01* lunatics or frauds. Which, of course, some of them are.

But we should get past that. Because nothing really cool ever happens without fanaticism. Fanatics see possibility everywhere. They believe the world can be changed. Big problems can be solved. By them. You and I, we hear of global warming, of toxic waste pollution, of sky-high garbage dumps and of ecosystem destruction, and as badly as we feel about it all, we also feel utterly powerless to do anything about it.

"Yeah," says Bill McDonough. "But I don't. And I don't think you should, either."

This is the thing about people who are out to change the world. They don't understand how the rest of us cannot get it. The opportunities are staring us in the face! The solutions are manifest! To be content with the status quo, or with incremental improvement, when so much more is possible—why, that's insanity.

Or at least, McDonough believes, it's not very interesting. "We accept the world the way it is and resolve to be less bad. Global warming? Drive a hybrid vehicle, and you're being less bad. But you're still producing global warming—just not as much of it. Being less bad is not being good. If you're supposed to be driving to Canada and you find yourself headed toward Mexico, its not going to help if you slow down to 20."

McDonough is in mid-rant now. He is a seductive proseltyzer and is, in any case, impossible to stop. It is a pleasant morning in Charlottesville, Virginia, and we are in the modest converted warehouse that is the world headquarters of William McDonough + Partners. Ours is the sort of what if conversation I remember having late at night with my freshman roommates—except this is pretty one-sided, and McDonough is dead serious.

McDonough—a distinctive, attractive guy—lives nearby in a house designed by Thomas Jefferson. Until recently, he was dean of the school of architecture at the University of Virginia—which Jefferson dreamed up as well. One senses that the comparison, though unmentioned, is not unintentional.

The rant proceeds. "We need a new story. How do we be 100 percent good?" One hundred percent good. That, McDonough thinks, could be something interesting. There is, he says, 5,000 times as much solar energy striking the earths surface than 10 billion people could ever use. If you had 5,000 times more money than your household needed, could you figure out how to make ends meet? A solar-powered world. "We can do that," McDonough says. "I think I can figure this out." Interesting.

McDonough is not the only ecologically minded designer out there. He's not the only guy experimenting with solar panels and natural air cooling and any number of exotic materials. He's certainly not the only architect with an ego.

But he is a strikingly creative thinker. He "has a remarkably clear and orderly mind," wrote Hollister Kent, an adjunct professor of art who taught McDonough, in a 1973 faculty citation—one of four the visual studies major was awarded at Dartmouth. His ideas are audacious in their scope and ambition. And he is, perhaps, the most compelling salesperson the green movement has ever seen.

"Five thousand years ago," he says, "there was someone walking down the Nile, looking at papyrus thinking, oh, I can mash that up and write on it. And that was a very interesting strategic moment, a brilliant observation of technology. But here we are centuries later, and we have people wandering around the forests of British Columbia thinking, I can smash that down and write on it. What are we thinking? And what do we do with it? We chlorinate it, we reduce it to the lowest quality product, and then we sell it all to the Japanese for next to nothing. And they're not even using it. They're just storing it because it's cheap. It just seems like a bad design to me."

And that's what McDonough is selling, of course: Good design. Well-designed work, and well-designed lives—because the ones we have don't make much sense. He understands that a better designed world depends on getting people to change the way they think and behave:?-and he'll do that by appealing to their imaginations. He imagines himself a mapmaker for decisionmakers seeking direction. So he rants, but it is a rant rooted in common sense and hope.

Before entering Dartmouth, an 18-year-old McDonough wrote that he wanted to become an "international lawyer or businessman." (Confronted with the document today, he says, "Wow. That's a long time ago.") During his freshman fall he took a course in the politics of the nuclear ageand another in basic design. And he thought the business of insubstantial talks and absurd treaties seemed so depressing. "It was a world I couldn't imagine getting caught up in. Design seemed more hopeful. The world could be a more beautiful place instead of a terrifying place. I realized! had an optimistic streak and I didn't want to beat my head against a wall."

So McDonough became a professional optimist, but one never so ungrounded that he could be written off. Can you imagine the manufacturing guys at Ford Motor on hearing that McDonough was going to cover their big factory with wild grasses? It was eco-socialist heresy—until McDonough spelled out the $35 million the danged grass would save over a conventional water treatment system. Plus, it will do a better job. And itwill looknicerto the birds flying overhead.

And that, for McDonough, is the nut of it. All this stuff—the grass, the technology, the ideas from left field—they're all about making the world...better! Not just sustainable. Sustainability—well, again, that's just not very interesting. "When I won the Presidential Award for Sustainability," he says, "a reporter came up and asked, 'How does it feel to be Mr. Sustainable?' I said, 'Are you married? How's your marriage?' If you say it's sustainable, I say, 'I'm sorry. Not interesting.' If Sustainability is just going to be the edge between destruction and regeneration, who cares?

"But what if we sustain culture? What if we sustain fecundity? That's where it gets interesting to me. The things we love are not efficient. One color, black. Very efficient. Children. Sex. I mean, efficiency? Can you imagine Mozart being efficient? Playing a piano with a 2-by-4 so he could get all the keys at once. What we like is the immense creativity and fecundity of the world."

Which is why, perhaps, people such as Bill Ford listen to McDonough. Yes, the grass could save Ford Motor $35 million, which will please the shareholders and analysts. But really,: the economics aren't yet demonstrated. It will be years before the savings from McDonough's designs are borne out.

It may be, simply, that business executives are tired of messing up the world. They don't want that in their obituaries. They feel as guilty and as helpless as you and I do, and they're looking for a guy with a map and a destination. Something better.

"I don't care what you do, how much money you make, how full of yourself you are," McDonough says. "If you're killing people and destroying the planet, you're killing people and destroying the planet. That's not a quality act. Is that how you want to spend your day? There are a lot of people who spend their day that way.

"We're just saying, spend it another way. We're not wagging our finger, saying you shouldn't be profitable. We're saying you should absolutely be profitable—but let's figure out what to do that makes some sense. And it's not going to be easy and it's going to take a long time."

a breath of fresh air

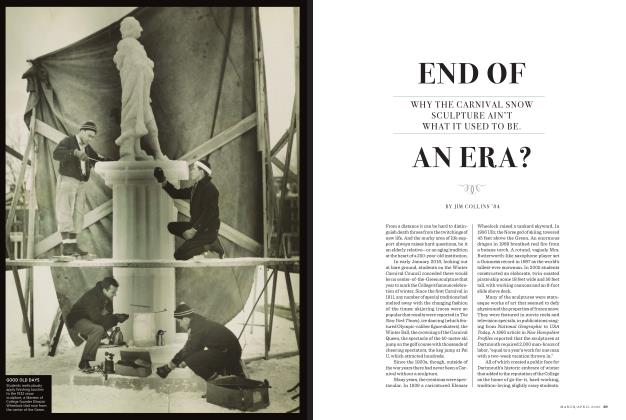

Oberlin College's center for environmental studies is one of the most advanced green buildings in the United States. Designed by William McDonough + Partners, the 13,600-square-foot building in northern Ohio requires about one-fifth of a typical classroom building's energy needs. Here's a look at some of its innovation!.

The Landscape A grove of trees andearthen berm protectthe north side of thebuilding (not visible).No pesticides areallowed in the gardens,orchards and restoredforest that reside justeast of the building.

The Sun Plaza The main entrance features a sundial that traces the solar seasons and marks solstices and equinoxes.

The Lighting A trellis and overhanging eaves shade the summer sun but allow winter heat. Glass panes are treated to vary amounts of ultraviolet light that can enter and leave the building, helping to maintain a more even temperature inside. Interior classrooms face south and west to take advantage of daylight and heat gain.

The Roof The building is oriented along an east-west axis to optimize passive solar performance and take advantage of prevailing breezes. Solar cells will eventually be replaced with more powerful versions that generate more than enough power for the building, which will then become a power source for other needs.

The Interior Designed to change over time, it includes carpeting that will be recycled for reuse, wooden chairs and desks made from a sustainable forest, and auditorium chairs made of biodegradable material. A total of 100 percent fresh air for ventilation is provided in all occupied spaces.

The Living Machine This wastewater purification system is not unlike the organic process that occurs in natural ponds and marshes. Wastewater is pumped here and microorganisms and plants break down the impurities. Next the water is stored for nondrinking reuse. Toilets are flushed and the process starts all over again.

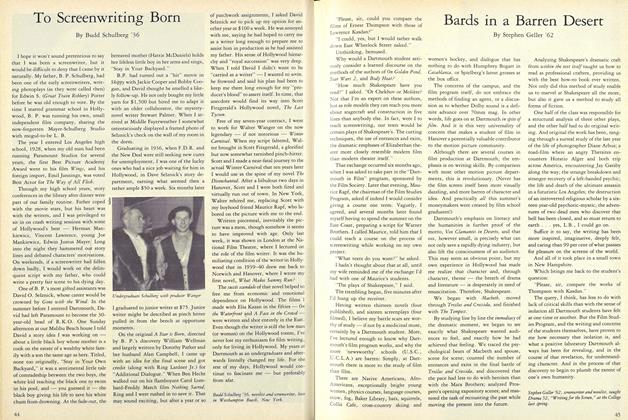

Flower Power McDonough kicks back on the vegetated rooftop he designed for Chicago City Hail, which sustains more than 100 species of flowers, grasses and trees. The plants lower summer air temperatures, minimize energy demands and manage stormwater runoff, among other benefits.

Radical by Design Grass grows on the undulating roof McDonough designed for a Gap building (top) in San Bruno, California; in its interior (bottom) you're never more than 30 feet from a source of natural light. McDonough's firm has also developed cloth (right) made with nontoxic dyes, greatly reducing manufacturing pollution.

As William McDonough knows, it takes plenty of attitude, ego and, yes, optimism. Keith Hammonds '81.

When you hear McDonough espouse his green ideas, many of them seem sosimple and so economical it makes one wonder why they're notbeing adopted more quickly. The answer is that the ideas are radical.

KEITH HAMMONDS is a senior editor at Fast Company magazine. He lives in Ossming,New York.

Brian Dumaine is the editor of FSB magazine. This article originally appearedin FSB as "Are You Ready for the Green Revolution?" Copyright © 2002 TimeInc. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Honor, To a Degree

September | October 2002 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

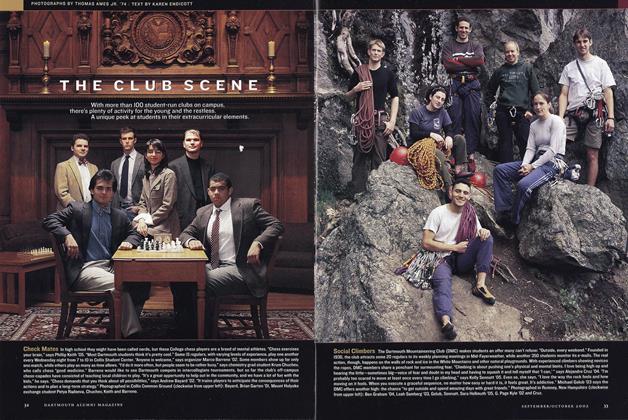

FeatureThe Club Scene

September | October 2002 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

September | October 2002 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryRiver Dance

September | October 2002 By Jonathan Agronsky ’68 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Aesthetics

September | October 2002 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1997

September | October 2002 By Abby Klingbeil