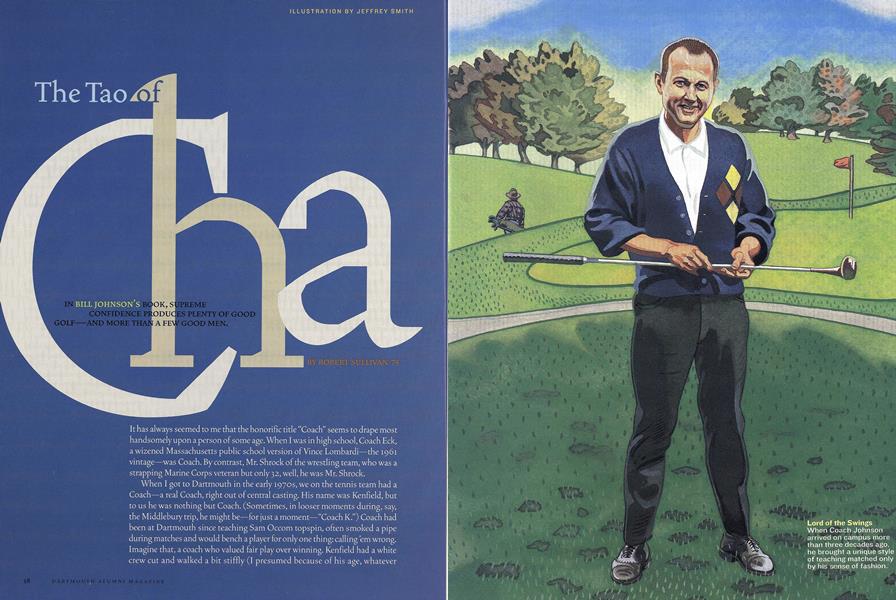

The Tao of Cha

In Bill Johnson’s book, supreme confidence produces plenty of good golf—and more than a few good men.

May/June 2002 ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75In Bill Johnson’s book, supreme confidence produces plenty of good golf—and more than a few good men.

May/June 2002 ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75It has always seemed to me that the honorific title "Coach" seems to drape most handsomely upon a person of some age. When I was in high school, Coach Eck, a wizened Massachusetts public school version of Vince Lombardi-the 1961 vintage—was Coach. By contrast, Mr. Shrock of the wrestling team, who was a strapping Marine Corps veteran but only 32, well, he was Mr. Shrock.

When I got to Dartmouth in the early 1970s, we on the tennis team had a Coach—a real Coach, right out of central casting. His name was Kenfield, but to us he was nothing but Coach. (Sometimes, in looser moments during, say, the Middlebury trip, he might be—for just a moment—"Coach K.") Coach had been at Dartmouth since teaching Sam Occom topspin, often smoked a pipe during matches and would bench a player for only one thing: calling 'em wrong. Imagine that, a coach who valued fair play over winning. Kenfield had a white crew cut and walked a bit stiffly (I presumed because of his age, whatever astonishing figure that might be). We loved Coach. He was the quintessence of what it meant to be Coach. He was the perfect Coach. In Webster's Collegiate, he was the illustration adjacent to the definition.

I felt bad for my friends on the golf team, and not just because they were engaged in such a wimp sport. Their coach, seen from across the playing fields, looked like a kid. He had a Beatles haircut—the 1965 vintage—and something of the band's 1965 cockiness, insouciance and joie de vivre. I could imagine him "relating" to his players "on their level," talking to them "in their language." I could imagine him sharing beers with them. Is that what you wanted in a coach, much less a Coach? It was not. I imagined that, in looser moments, my friend Jerry Daly '76, a member of the golf team, might be calling this guy "Bill." Then one day I did overhear jerry call out to him and, indeed, he did not call him Coach. He said, "Hey, Cha!" I was appalled.

Lo these many years later, I approached members of the Dartmouth golfing fraternity, including the man himself, to inquire about Bill "Cha" Johnson upon the occasion of his retirement after 35 years. I went to them wondering whether, over the many seasons, this guy once known to his charges as Cha had become Coach. Had he, "in his venerability, grown into a Kenfield? And if he had, what was that journey like—traveling from coach to Coach? The first thing I learned was that he was still Cha. The second thing was that he had, indeed, made the journey.

THE TRIP BEGAN NOT IN NEW HAMPSHIRE BUT IN THE Midwest. Bill Johnson was born 62 years ago in Michigan and was an all-sports kid in his adolescence. He liked golf fine, but never figured it for a career; at the University of Michigan he planned to become an engineer. But when you're fresh out of college, you sometimes take the job that looks like fun. In his early 20s Johnson was a very young golf pro at the tony St. Clair Inn and Country Club in Detroit. "I was working for a Dartmouth grad," says Johnson. "I didn't like it there, having to learn the social graces of this big club. I saw good people coming in, plastic people going out. They took lessons because it was the thing they were supposed to do. They weren't dedicated to the game. The manager and I discussed how the Hanover job might be opening up—after a million years, golf coach and Hanover Country Club manager Tommy Keane might be leaving. I had been in the Upper Valley a few years earlier on a visit and really liked the place and the attitude of the people. I figured people like those, if they signed up for a lesson, they'd want to learn. So I got in line for the job."

couldn't have done that, nor did he want to—but, rather, that one lengthy era ended and another began. "Keane was this squat little Irishman who was loved and revered by everyone, and had been for 45 years," remembers John VanDyke '67, a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley. "After a match we'd sit around having beers with Tommy, and in this thick New Hampshire accent he'd tell us how we did with one of his sayings, such as, 'Way-yull, watah seeks its own level.' He had all these sayings. Now, we never learned a thing about golf from him. His job was to drive us to the meets. But he was a great human being, and we loved him. It's not that Johnson stepped into Keane's shoes in 1967—he

"Here comes Bill, who wasn't much older than we were, and I'm sure we gave him a terrible time. We figured we were smarter than he was and I'm sure we weren't very nice. But Bill stuck with it. He won our respect when we found out he knew something about golf and could doctor your swing a bit, which was a revelation to us."

From his vantage on the other side of the ball, Johnson saw the situation much the same way. "They reacted sarcastically and negatively at first," he says. "So I had to make some wholesale changes in attitude. I think it scared em. Look, I don't really care if you lose, but if you're not dedicated to doing your best, I've got no use for that."

Johnson achieved results quickly. In 1969 his team lost its first match, then won the rest. Heading into 1970 it looked, on paper, just as strong. "But then we got to Florida for the spring trip and right off I saw the problem," says Johnson. "The guys were joking about how maybe they should lose the first match, then they'd win all the others, like last year. It upset me. I wanted to see confidence. I've always said, 'lf you think you can or think you can't—you're right.' So I told them, 'Hey, you guys are good enough to win them all and get to the NCAAs. You start thinking like that.' They went away and talked it over, then came back and said, 'Okay, we're with you. But here's the deal: You can't cut your hair till we lose.' "

The anecdote delivers us at two significant Johnsonian aspectshis adages and his image—and so we head off on twin tangents.

"If you think you can or think you can't—you're right" is only the most famous and easily understood of several Cha-isms (which probably aren't much different from Keane-isms, such as water seeking its level). Johnson lives and teaches by the rules of his very personal, quirky Tao. "He's got a million sayings," says Joe Henley' 79. '"Confidence, not cockiness,' he used to say, and 'lt isn't who you beat but how well you feel about how you played.' " Others from the Book of Cha: "A good score is the mere accumulation of shot values." "Cold is just a figment of the imagination." "A par-5 is something, something and a wedge." "That's as good as good." "Grip the carpet with your toes." "There's a permanent cloud over New Haven." "Use an open stance at the water cooler." "A dogleg is just two straight shots in different directions."

The maxims, as can quickly be seen, are meant to deliver an athlete to a point of steeled nerves and brimful pride. "Yes, I believe in supreme confidence, not cockiness," Johnson confirms. "There's a difference." If some would argue the line is blurry ("Our Ken Kotowski '68 was definitely cocky," says Van Dyke. "Joe Henley was as cocky as they came."), this hardly mattered to Johnson. It produced good golf and allowed young men to feel good about themselves.

As to the image: It is a reasonable assumption that Johnson is personally responsible for the multitude of jokes that have been made through the years at the expense of golf attire and grooming. In the 1960s he wasn't so bad. He wore a butch cut, chinos, a golf shirt with a too-big collar—but, as said, the whole package wasn't awful. Beginning that day in Florida in 1970, however, Johnson began a descent into egregiousness that is without parallel this side of Bill Murray's Pebble Beach hat. First came the hair. The 1970 team was very good indeed, and by the time they had won the New Englands and were headed to the NCAAs at Ohio State, Bill was the fifth Beatle. The fifth Beatle look doesn't really go with golf clothes, certainly not early-1970s golf clothes, but Bill didn't seem to notice. He's unapologetic about this."l kind of liked the flared pants," he freely admits. He liked colors, too, which was unfortunate. Patterns as well. Yes, there were plaid pants. And those pants were not made of cotton,

or any other fiber known to nature. Now, here comes the horrible part. Bill, in consultation with his captains, selected the team uniforms. In other words, he put subservient young men, each of them eager to please Cha, into the same clothes he was wearing. He should have been brought up on charges.

But he was not, and his players throughout the 19705, a colorful bunch in more ways than one, received the benefit of his instruction and went on to achieve considerable success for golfers who had enlisted at a snowbound school. Kotowski, Sandy McWilliams '70 (All America his senior year), Henley (All America in both 1978 and 1979), Daly (a two-time captain).

How responsible was Johnson for their success? "Very," says Henley. "He instilled confidence whether you were on the top of the ladder or the bottom. He prepared the team extremely well. He charted courses for us when other coaches were just playing practice rounds. Ask him about Dots and Stars."

Henley's suggestion is followed, and in a blur of explication Johnson outlines Dots and Stars, which he really should trademark. Essentially, Johnson, in scouting recruits or the enemy, wants to know the difference between the guy who shoots 75 and is overachieving and the guy who shoots the same and is underachieving. If Johnson makes a correct assessment, then he'll be able to predict who will shoot 74 the next day and who will shoot 76. Johnson assigns or deducts points for cornerstone items such as fairways hit (or not), greens in regulation, three-putting (or not). Tiger Woods, when winning, is in the low 50s under Dots and Stars, while a Dartmouth player doing well reaches the lOW 4OS. "Ifyou can score a 33 you can play for Dartmouth," Johnson sums up. "The average points for our starters used to be 27, now it's 34." Johnsons a techie: He long ago used a graph-check sequence camera for stroke analysis, and back before there were 150-yard markers on courses he conspired with a Dartmouth geography major to acquire aerial photos of the Myopia Hunt Club course in Massachusetts so that Dartmouth golfers could see the hidden bunkers and gain an edge—a winning edge, as it happened—over Harvard.

Johnson likes to talk about gadgets and gimmickry, but it is something non-material that was most important to the team. Consider the case of which Johnson is proudest. Joon Sup Lee '84 came to Dartmouth for an education, not just to play games. He tried golf as a freshman and sophomore but couldn't make the team. Then he went at the game hard his junior year and, in his final spring, made the traveling squad. Meantime, he was Phi Beta Kappa. A story like that isn't built without a Coach. "Bill was fun and informal, but always proud of his team and of Dartmouth—coats and ties when we traveled, for instance," remembers Bruce Pfaff '76. "He was my favorite prof at Dartmouth, though I didn't learn that until later."

Perhaps the finest of the golfers of the glorious 1970s—or any Johnson era, for that matter—was Daly. As I remember Jerry at that time, he was a charming, unassuming young man; you never would have supposed he was a great golfer if you didn't hear his teammates speak of him with such awe. "He was the best striker of the ball I ever had," Johnson says. "If he had been a more dynamic putter, he was right there with the great golfers." Daly was Johnsons only four-time All-America selection, and that about says it.

But he was more, too, and his relationship with his coach points to an intimacy that Johnson allowed between himself and his players. "I have this rule of coaching," Johnson says, unsurprisingly. " 'Be firm, be friendly and be fair.' So under that rule, I do get to be friends with my players, if the conditions are right and we have mutual trust and respect. Jerry and I became close friends. In fact, he was best man at my wedding."

That would have been in the spring of 1979. In 1976 a National Golf Foundation seminar had been held in Hanover and one of the attendees was a schoolteacher named Izzy Emslie who, as a child in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, had learned to play expertly on the DuPont course and now was thinking that maybe there were career opportunities in the game. As you would expect of a golf confab, there was time for golf. "I saw her play," remembers Johnson. "She had a superb short game, but she wasn't hitting it long off the teecouldn't hit it out of a paper bag." (Note: In the Tao of Cha, there are adages, and there are mangled metaphors.) "So I said to her, 'How'd you like to hit it 30 or 40 yards further?' What a line, eh? She threw her arms around me. Would I?!' "

Izzy's drives got longer; their love deepened. "I had to go to my mom," Izzy recalls. "I said, 'Now, Mom, he does wear some wild clothes.' "It was okay with Mom and the match was made. Izzy became something of a partner in running the Hanover Country Club and, in 1981, the founding coach of the Dartmouth women's golf team. Bill and Izzy settled in a house in Hanover hard by the river; "You can fish off the dock," says Bill. They both loved their coaching and the club, and Bill loved, as well, his sideline jobs and recreations, which included squash, bowling and teaching his golf phys ed classes. "It was inspiration to get kids that cared," he says. "I'd bring out weird equipment and drills, and some of them got truly interested. That's what I live for."

Danny Blanch flower—well, professor David G. Blanch flower of the economics department—was a regular at the club, not to mention a Friend of Bill's, and he saw the "weird equipment and drills" firsthand. "He'd have people swinging brooms," says Blanch flower. "He'd have heavy things with wiggly bits on the end. He was a character, that was how he was seen at the College: as a character. Who's not drawn to such a man? He was an artist and, particularly with his team, he was looking for artists. He'd do these odd drills, hitting through bushes. They listened to him as to a maestro. They were in awe of him." Certainly during the famous Bush Drill, they were at least dumbstruck. "Gentlemen, did you know that during the first 10 to 15 feet of a ball's flight, the ball actually oscillates," Johnson would say Cha-racteristically as he took a stance. "Gentlemen, 90 percent of the time the ball will go right through the bush because of oscillation." He'd take a whack and his oscillating ball would burst through the bush and go flying down the fairway.

Blanch flower was a regular partner, playing for a one-pound note per round, in deference to the economists Britishness. And there were other FOBs among the faculty. Former English department chair Henry Terrie has shared more than a few 18s with Bill and once, years back, the two of them engaged in a series of matches with legendary pro Gene Sarazen, who lived down in New London, New Hampshire, and his partner, a professor from Colby. Another legend played the closing three holes at Hanover against Johnson once, this fellow named Jack Nicklaus, whose son was being was even on the 18th Johnson sank an eagle putt and won the Bud, though Jackie Jr. wound up matriculating at a golf college.

But mostly Johnson played with the kids on the team. He freely admits it kept him young, and it is what he'll miss the most. "Even in the later years, if they wanted a piece of me, I'd say, 'C'mon,'" he says with cocki...with supreme confidence. "I wouldn't bet money, but Id bet them a shoe shine. And I hate to shine shoes."

While much was good for Bill Johnson in those years, principally Izzy and coaching, it wasn't all blue skies. There were light clouds and darker ones, too. The insignificant cumulus had to do with golf, while the true storms had to do with life itself.

With the advent of Tiger, golf boomed, as we all know, and this wasn't necessarily a good thing for schools such as Dartmouth. "We still got players who wanted the education, but some top golfers looked at the money that could be made in this sport and the golf colleges got stronger." Also in the cirrocumulus category of troubles, there was that tempest in a beer barrel. "We used to keep cold ones in a cooler at the country club, and members could have a beer for 50 cents," says Johnson. "Someone squealed to the Liquor Control Commission and the administration yelled, 'We're not going into the liquor business!' Finally, it worked out okay, and Izzy and I opened Colonel Bogey's at the club in 1977. It's a nice 19th hole." The incident seems trivial in recounting, but it was indicative of a larger problem facing Johnson. Cha was becoming, in his way, Tom- my Keane. In the 1960s Keane found himself, while still beloved by his players, out of step with administrators who wanted coaches to coach, and perhaps drink fewer beers with the boys. Cha, always a character—one who probably appeared to Parkhurst Hall much as he appeared to me in 1975, i.e., a maverick and a smart alecksuddenly started to look like a politically incorrect smart aleck. If there was a bit of disillusion, it went both ways. "There's been a creeping impersonalization of campus life," says Johnson. "The telephone is not very often used, it's all Blitz now. There's an intimacy lost. The kids' increasing course load makes sports difficult. I understand that, but, still, in recent years my favorite times have been getting in the van and crossing the bridge, heading for a match and leaving the rest behind."

Those were the nuisances. The bigger trouble included a heart attack, suffered 12 years ago. From the seizure, he recovered completely, but from the cruel misfortune that has befallen an unfair share of his players—his dear friends—he never will. Mark Trauner, a jayvee player in the class of'83, died of brain cancer a few years ago. "One of the toughest things I ever went through," says Johnson. He adds stoically, "I had a player on the 102 nd floor." That would be Jeff LeVeen '68, who was captain in his senior spring and who was, on September 11,2001, on the 102 nd floor of the World Trade Center. Then there was the boy Johnson coached at the club—not a Dartmouth player, but a local lad. His name was Jeff Julian, and certainly he was Johnsons all-time charge from the area. He was close to qualifying for the PGA Tour when he was diagnosed not long ago with Lou Gehrig's disease. And then, in early February, jerry Daly died of brain cancer, and his friend and coach—not to mention all others in the Green golfing community—was visited again by a terrible sadness. "These things can be tough," says Johnson. He doesn't say more, and then, suddenly, he does.

"The old adage about coaches, that they appreciate 'heart'—I hope most coaches understand what that is."

There is no such old adage. It's one of Cha's.

Cha looked around-when, 10 years ago? five?- and found himself venerable, if not old. Much water had gone beneath the bridge, and he was a different man, even if he was still Cha. There were reasons to pack it in, and one big reason not to: the kids. His team as he headed into the new millennium had "two legitimate stars" in Lee Birchall '02 and Jeronimo Esteve '03, and these players certainly wanted him to stay. "He was always young at heart, and I say this looking at some of the other coaches you would perceive as old," says Birchall. "We had a very nostalgic feeling for him near the end, that if he left he was going to miss being around people our age." Avery good recruit coming into his own at Dartmouth was Jeremiah Daly '04, son of Jerry, and how could Johnson leave that? But, finally, they were redesigning the golf course, making it bigger, looking toward a new era at Hanover C.C....He was already in the Golf Coaches Hall of Fame, had been for a decade....He had taken 17 players or teams to the NCAAs.... He'd worked more than 10,000 hours with only nine days sick leave (especially proud of that)....He had traveled more than a million miles to matches with his boys and....

It was time.

The guys planned a surprise party last summer, of course. They love Cha and had to give him a send-off before, he and Izzy headed for North Carolina and a retirement that will include teaching golf at clubs and clinics. They presented him with pictures and stories and some of the more outrageous pants of the many outrageous pairs he had worn in his day. "Oh, Bill," groaned Izzy, as is her custom.

The party was well over when I went back to some of the players and to Johnson himself and asked a question I'd forgotten to ask. What's with this Cha thing? What's Cha all about?

"It means Coach," says Henley. "In the 1970s, once Bill was really the coach of this team, the guys just before my time had their own language." (As would any fine group of immature collegians, I did not add.) "What it was: They added an 'a' onto the last consonants of any name, and then they could understand one another but no one else could. Even if you were talking about a guy—Tom—in front of him, it would be Ma, if he happened to over-hear. You take the 'ch' in coach, and it was Cha."

So he had been Coach, if not all along, then for a very long time. Of course he had, one as good—and firm and friendly and fairas he. My original theory was in ashes. If you're the right coach with the right attitude and the right dedication and the right sense of fair play—plus a respect and affection for your players—then you're Coach, whether you are 28 or 78. Kenfield had.probably been Coach as a young man, too. Remarkable.

I now remember a few minutes of conversation with Coach Johnson vividly, though I wasn't taking notes. I mentioned this fact: I had seen him from afar, and he had seemed very young, as I was in thrall at the time to old Coach Kenfield. Coach Johnson said he remembered Kenfield well. We talked a bit more about those years, about this and that. In any event, Coach Johnson finally said, "He certainly was a fine gentleman."

To which I would add, right back at Cha.

Lord of the Swings When Coach Johnson arrived on campus more than three decades ago, he brought a unique style of teaching matched only by his sense of fashion.

Parting Shot Before retiring to North Carolina, Johnsonspent last summer helping oversee renovations at HanoverCountry Club, which reopens this summer.

ROBERT SULLIVAN is a senior editor at Time magazine.

"IF YOU THINK YOU CAN OR THINK YOU CAN'T—YOU'RE RIGHT" IS ONLY THE MOST FAMOUS OF THE CHA-ISMS THAT JOHNSON LIVES AND TEACHES BY.

"BILL WAS AN ARTIST AND, PARTICULARLY WITH HIS TEAM, HE WAS LOOKING FOR ARTISTS. HE'D DO THESE ODD DRILLS...AND THEY LISTENED TO HIM AS TO A MAESTRO." —PROFESSOR DAVID BLANCH FLOWER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

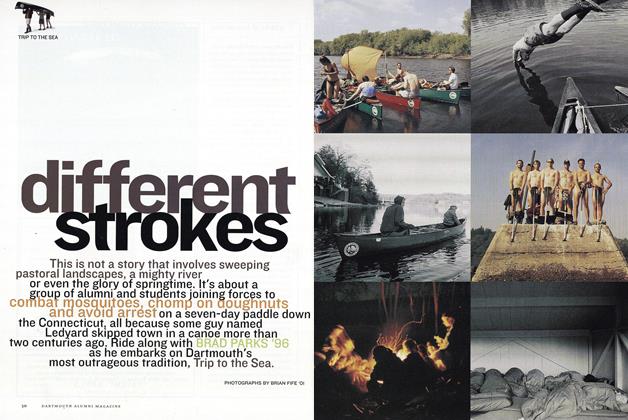

Cover StoryDifferent Strokes

May | June 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryOut of Bounds

May | June 2002 By Sarah Lang Sponheim ’79 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

May | June 2002 -

Article

ArticleFalse Sense of Security

May | June 2002 By Professor Allan C. Stam -

Article

ArticleThe Gift of Education

May | June 2002 By President James Wright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

May | June 2002 By Nihad M. Farooq

Sports

-

Sports

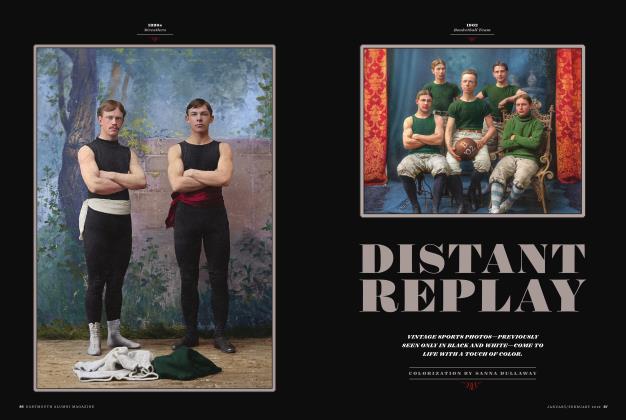

SportsDistant Replay

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2019 -

Sports

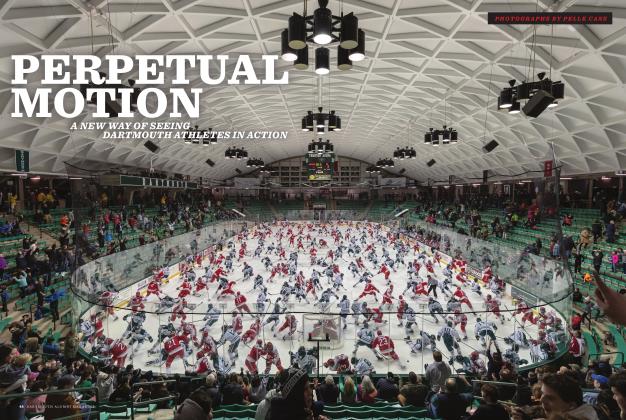

SportsPerpetual Motion

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2019 -

Sports

SportsThe Digital Recruit

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By ADAM BOFFEY -

SPORTS

SPORTS“A Dark Hole”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By ADAM ESTOCLET '11 -

SPORTS

SPORTSGame Changer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

SPORTS

SPORTSThree-For-All

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By CHARLES MONAGAN ’72

ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

December 1990 -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July/August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

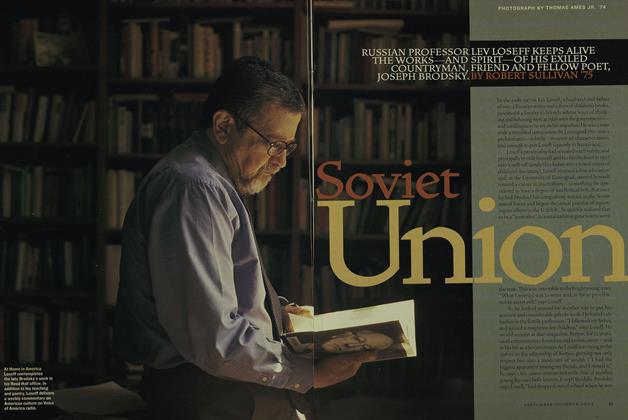

FeatureSoviet Union

Sept/Oct 2005 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

July/August 2008 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

RETROSPECTIVE

RETROSPECTIVEHe Wept Alone

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75