Few of the procedures and tests you undergo each year have been scientifically proven to work. When doctors fully understand and can explain the true risks and benefits of a treatmentrather than act on intuition—their patients often want less care, not more.

The first step toward improving the quality of health care is reducing what Dr. John Wennberg's group calls supply-sensitive care, the excess procedures, hospital admissions and doctor visits that are driven by the supply of doctors arid hospital resources rather than by need. The Medical Excellence Demonstration Program Act, a bill introduced two years ago by Vermont Senator James Jeffords, is a step in the right direction. It would call on several medical centers around the country to model high-quality medicine that also reins in costs. Organizations such as the American Medical Association and groups such as Kaiser Permanente (the nation's largest nonprofit health care organization) will need to set benchmarks for more conservative practices and for measuring patient outcomes.

Benchmarks are also needed to ensure that doctors deliver less care that doesn't help patients and more "evidence-based medicine," procedures and practices whose benefits are scientifically proven. The manifesto of the evidence-based-medicine movement was published in The Journal of the American Medical Association in 1992. Its authors, a group of physicians led by internal-medicine specialist Gordon H. Guyatt of Ontario, argued that too much of what doctors do is based on intuition—not science—as the vast majority of medical therapies have never been evaluated by systematic study. Indeed, many Americans would probably be surprised to know how few of the procedures and tests they undergo each year have been proven to work.

Take mammography, for instance. About 30 million American women undergo a mammogram each year in the hope it will detect a breast cancer early enough that doctors can cure it. But mammograms, it turns out, may not be nearly as effective at saving lives as

most doctors and patients assume. Seven different clinical trials involving more than 100,000 women have been conducted in the United States and Europe during the last 25 years in an effort to determine whether mammography reduces a woman's chances of dying from breast cancer. The results were conflicting: Four said it reduced a woman's risk; three said it did not. And two years ago a paper published in the British medical journal The Lancet called into question the methodology of the four studies that found mammography benefited women.

Another way to assess the power of mammography to save lives is to look at the death rate, or number of women per 100,000 in the population who die from breast cancer. That rate has dipped only slightly in the last few years, despite the millions of women who now dutifully get their mammograms. Some researchers believe that the credit for the lowered death rate should be given not to earlier detection of breast cancers but rather to new treatments such as the drugs Herceptin and Tamoxifen.

Mammography's shortcomings are shared by several other screening tests for cancer, including the prostate specific antigen (PSA) test and spiral CT scanning, a new technology that is being touted as a way to detect smaller and smaller lung cancers. The trouble with such tests is that tumors come in many types, only some of which will ever become aggressive enough to threaten the patient's life. Unfortunately, radiologists and pathologists can't tell with much certainty how aggressive a particular tumor is going to be. "Imaging has improved so much, we can find things that we really don't know enough about," says Dr. William Black, a member of Wennberg's team and a radiologist at Dartmouth Medical School. In the face of this uncertainty, doctors say they must err on the side of caution and treat practically every tiny tumor as if it were potentially deadly in the hope of curing at least a few.

That means that widespread screening for prostate, breast and lung cancer has resulted in huge numbers of patients suffering the side effects of unnecessary medicine. Removing the prostate gland, which sits at the base of the penis, is, not surprisingly, a delicate surgical procedure that renders many patients impotent, incontinent or both. A study published last October in BMJ (formerly the BritishMedical Journal) compared PSA testing rates in the region around Seattle and in Connecticut between 1987 and 1997. Men in Seattle were 5.39 times as likely to get a PSA test as men in Connecticut and five times as likely to undergo surgical removal of the prostate. Yet there was no significant difference in the death rate from prostate cancer between the two regions.

Unfortunately, the flip side of patients being given unnecessary or unproven surgery is not necessarily getting procedures that have been demonstrated to work. Three recent studies conducted by the Institute of Medicine, the RAND Corp. and the Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality report widespread "underuse" of evidence-based treatment such as balloon angioplasty or a stent to open blocked arteries during a heart attack, even among citizens with gold-plated health insurance. Dartmouth professor of medicine Elliott Fisher has recently found that highest spending regions of the country often do a poor job of providing patients with such basic care as flu shots for the elderly.

Wennberg would like to see the nation's academic medical centers and the National Institutes of Health step up to the plate and conduct more clinical studies that can demonstrate the true effectiveness of medical treatments. "Academic medical centers have lost sight of the fact that they are supposed to be building the scientific basis for medicine, not pushing treatment that will make a lot of money," he says. At the same time, medical schools and organizations have to create mechanisms for speeding up the glacial pace at which results from such trials now creep into clinical practice. According to a recent Institute of Medicine report, it takes 17 years on average for doctors to abandon traditional practices that are ineffective or to adopt those that are scientifically proven.

In those instances when the efficacy of treatment is uncertain, doctors will have to cede more decision-making to patients. That means taking time to help patients understand the risks—as well as potential benefits—of medical procedures ranging from back surgery to PSA tests, and such decisions as whether or not to admit an elderly person with multiple ailments to the hospital for pneumonia. When patients know the true risks as well as the possible benefits, they often want less care, not more—and are happier about their decisions. A recent study conducted at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center found that when patients suffering from back pain viewed a video that laid out the evidence for and against back surgery, they were more likely to decide not to go under the knife than a similar group of patients who simply talked to their doctor about their options.

Simply helping patients make informed decisions will almost certainly help reduce excess treatment. And the money saved on needless care that is wasted on patients who don't need it could be invested in patients who aren't getting enough.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Overtreated American

November | December 2003 By SHANNON BROWNLEE -

Feature

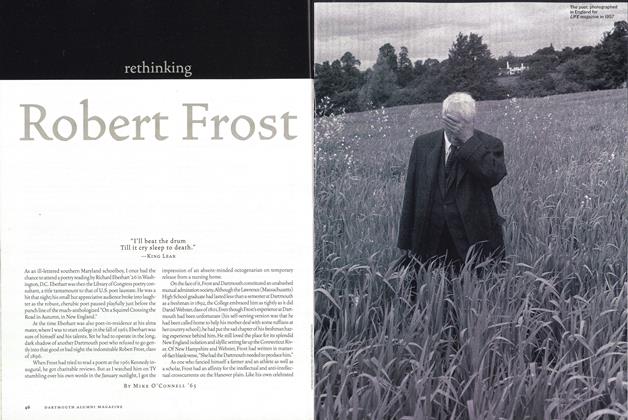

FeatureRethinking Robert Frost

November | December 2003 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Feature

FeatureSimply Seth

November | December 2003 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2003 By DAVID DEAL, DAVID DEAL -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2003 By John Kemp Lee '78, THE KOUROS GALLERY, NYC -

Personal History

Personal HistoryBody Of Knowledge

November | December 2003 By Kirsten Andrews ’97

Article

-

Article

ArticleREMARKS OF PRESIDENT TAFT AT THE THIRTY-FIFTH ANNUAL DINNER OF THE WASHINGTON ALUMNI

January, 1910 -

Article

ArticleOVERSEAS STUDY DATA AVAILABLE AT DARTMOUTH

May 1920 -

Article

ArticleNew Dartmouth Hall to be Fireproof

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleAfter Fifty Years

July 1940 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meets

December 1943 -

Article

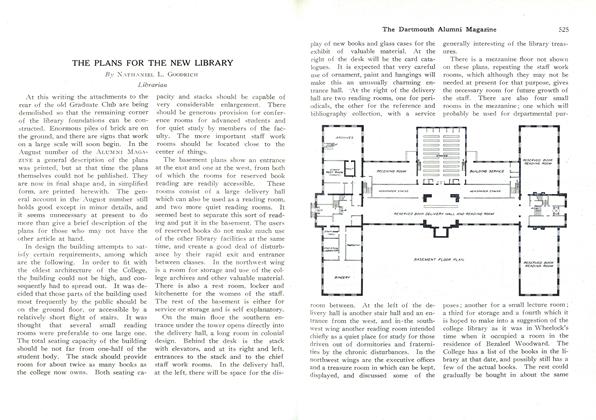

ArticleTHE PLANS FOR THE NEW LIBRARY

APRIL, 1927 By Nathaniel L. Goodrich