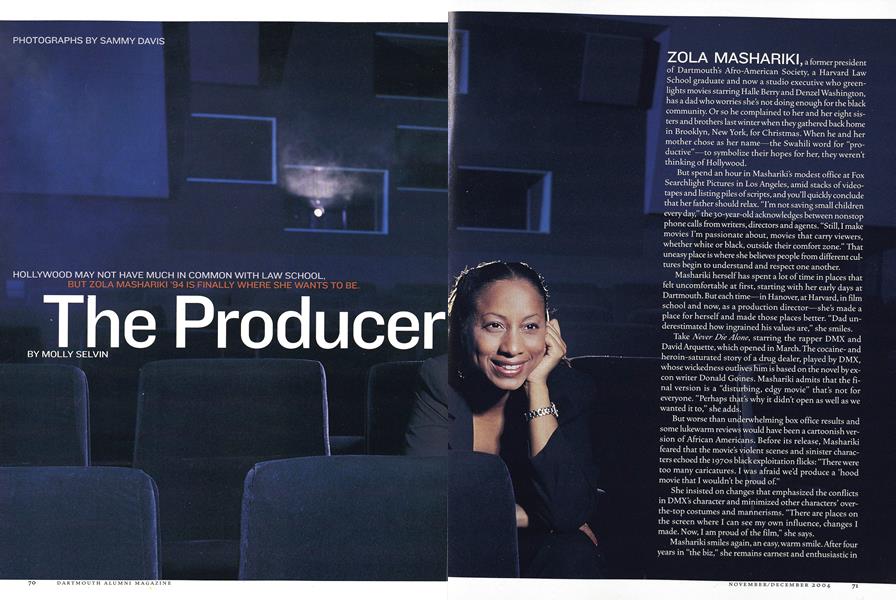

The Producer

Hollywood may not have much in common with law school, but Zola Mashariki ’94 is finally where she wants to be.

Nov/Dec 2004 Molly SelvinHollywood may not have much in common with law school, but Zola Mashariki ’94 is finally where she wants to be.

Nov/Dec 2004 Molly SelvinHOLLYWOOD MAY NOT HAVE MUCH IN COMMON WITH LAW SCHOOL, BUT ZOLA MASHARIKI '94 IS FINALLY WHERE SHE WANTS TO BE.

ZOLA MASHARIKI, aformer president of Dartmouth's Afro-American Society, a Harvard Law School graduate and now a studio executive who greenlights movies starring Halle Beriy and Denzel Washington, has a dad who worries she s not doing enough for the black community. Or so he complained to her and her eight sisters and brothers last winter when they gathered back home in Brooklyn, New York, for Christmas. When he and her mother chose as her name—the Swahili word for "productive" —to symbolize their hopes for her, they weren't thinking of Hollywood.

But spend an hour in Mashariki's modest office at Fox Searchlight Pictures in Los Angeles, amid stacks of video- tapes and listing piles of scripts, and you'll quickly conclude that her father should relax. "I'm not saving small children every day, the 3 o-year-old acknowledges between nonstop phone calls from writers, directors and agents. "Still, I make movies I'm passionate about, movies that carry viewers, whether white or black, outside their comfort zone." That uneasy place is where she believes people from different cultures begin to understand and respect one another.

Mashariki herself has spent a lot of time in places that felt uncomfortable at first, starting with her early days at Dartmouth. But each time—in Hanover, at Harvard, in film school and now, as a production director—she's made a place for herself and made those places better. "Dad underestimated how ingrained his values are," she smiles.

Take Never Die Alone, starring the rapper DMX and David Arquette, which opened in March. The cocaine- and heroin-saturated story of a drug dealer, played by DMX, whose wickedness outlives him is based on the novel by excon writer Donald Goines. Mashariki admits that the final version is a "disturbing, edgy movie" that's not for everyone. "Perhaps that's why it didn't open as well as we wanted it to," she adds.

But worse than underwhelming box office results and some lukewarm reviews would have been a cartoonish version of African Americans. Before its release, Mashariki feared that the movies violent scenes and sinister characters echoed the 1970s black exploitation flicks: "There were too many caricatures. I was afraid we'd produce a 'hood movie that I wouldn't be proud of."

She insisted on changes that emphasized the conflicts in DMX's character and minimized other characters' over- the-top costumes and mannerisms. "There are places on the screen where I can see my own influence, changes I made. Now, I am proud of the film," she says.

Mashariki smiles again, an easy, warm smile. After four years in "the biz," she remains earnest and enthusiastic in a town where the air kiss passes for genuine affection. Guiding a visitor around the historic Fox lot, past the New York street facade first used in Funny Girl and now for NYPD Blue, Mashariki muses, "You can get inspired here." In this world of designer labels, she prefers casual, tromping past Fox's sound stages in sandals, a turquoise plaid wrap dress and a velour sweatshirt. Perhaps the casual look is rooted in her time in Hanover, but she has always made her own decisions.

A white, Ivy League school wasn't exactly what her dad, a for- mer bookstore manager, had in mind for his daughter. But after visiting, she decided that four years at Dartmouth was a challenge she should embrace.

Zola was 5 when Job Mashariki founded Black Veterans for Social Justice to help Vietnam-era servicemen who were due benefits. In its 26th year, the nonprofit group now serves veterans of all races and also runs a homeless shelter and AIDS hospice. Zola's mother, Akilah, now retired, was one of IBM's first African-American managers in Brooklyn.

Zola remembers a childhood filled with art lessons, dance classes and parents who set aside evenings for family members to read to one another. Academic success was expected, and Zola more than met the challenge, entering first grade at age 3 and Dartmouth at 16. Job remembers her as a very bright little girl who made up for being a bit shorter than her four older sisters with a fierce drive to succeed.

Some families devote their weekends to Little League or their children's soccer tournaments. Politics was the Mashariki pastime. The Mashariki kids, as often as not, were rousted out of bed on icy weekends to boycott a local bodega that had mistreated black customers or to march for veterans' rights. "I'm so happy to lie in bed Saturday mornings now," Zola sighs.

Her parents' support for Black Panther Assata Shakur and other political activists sometimes generated questions from FBI agents. Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X's widow, was a close family friend. (Before her marriage, while she was a student at Long Island University, Mashariki's mother was active in the Brooklyn Congress of Racial Equality chapter that invited Malcolm X to speak on campus.)

As a teenager, Mashariki remembers trailing her dad to a Brooklyn community group where David Dinkins, another family friend, was testing the waters for his 1989 run for New York City mayor. She later worked in Dinkins' campaign—Mashariki recalls the mountains of tuna sandwiches she and her mother made for fundraisers—and attended the new mayors inauguration.

No surprise, then, that when her college offers arrived, Mashariki's dad pushed hard for a black college or a public university— definitely not an Ivy school where she might forget where she came from. "He gave me this lecture about being a big fish in a small pond or a small fish in a big pond," she remembers. But Mashariki insisted on visiting Dartmouth to meet the other African Americans admitted. "I feared they'd be Martians or oppressed but instead they were cool," she recalls. Her dad fumed at her enthusiasm and, to underscore his opposition, declared he wouldn't pay Dartmouths tuition. "I didn't want her culture subverted or dissipated," he remembers now. "Dartmouth seemed distant and very limited in terms of African-American culture."

"Zola, forget what he said, you're going to Dartmouth," her mom counseled—and then paid her daughters freshman tuition. By sophomore year, Mashariki's father had come around after seeing how much she loved the place.

Ten years after graduation, Mashariki's Dartmouth years still hold enduring lessons in the power of faith, hard work and chance. Her freshman outing was Lesson 1. Mashariki had heard that the kids on these trips often become lasting college friends. She took a flier on kayaking, something this self-described "city girl" had never done. When she saw that all her fellow kayakers were white, she drew a deep breath and silently resolved, "I have to be open to this."

"I sucked at kayaking but I never had so much fun in my life," she says now. Fourteen years later, that trip remains for her what Dr. Phil might call a "changing day." "What would have happened if I didn't check that box?" she still wonders.

That plunge led to other brand new experiences, including skiing ("I skied right into the parking lot!"), horseback riding and a sophomore term in Spain. "Coming from an all-black community, I never thought that I'd feel comfortable in a foreign country," she says. But she did, surprised that what seemed to matter more than her race and gender was her nationality. She now calls Spain her "second home," and remains close to the family she lived with in Granada.

That freshman kayaking trip also led Mashariki to what has become her profession and her passion. Having grown up in a house where the kids weren't allowed to watch much TV or see many plays or movies, she started directing plays and acting at Dartmouth. "Drama became my vehicle to educate whites about my culture. I had no idea my job even existed," she says.

She wrote Mahogany Waves, a one-act play about four black women who meet at the funeral of a man they all knew. Her production was part of the Colleges Eleanor Frost Playwriting Competition. As artistic director of Dartmouth's Black Underground Theatre and Arts organization in her senior year, Mashariki directed For Colored Girls, a play by Ntozake Shange about young women overcoming conflict and finding themselves. The three-day run sold out to racially mixed audiences, as did an encore performance a few weeks later.

An officer in the Afro-American Society for most of her time at Dartmouth, she helped organize a full schedule of activities and events for black students, including a lecture by Betty Shabazz and a screening of Boyz 'N the Hood at Shabazz Hall. The movie drew white fraternity guys who'd never been through the door of that house and later told Mashariki, "I'm glad I came."

As one of just 51 black students in her class, Mashariki remembers awkward moments. "How often I washed my hair became an issue. I'd have to say that just because our hair has different texture and we don't wash it every day doesn't mean that we're dirty," she says.

Mashariki left as big a mark on Dartmouth as it left on her. She graduated with honors, was named "Outstanding Woman in the Senior Class," and picked up the Nguzo Saba Award for Excellence in Scholarship, Leadership and Service; the Martin Luther King Leadership Award; the Benjamin and Edna Ehrlich Prize in the Dramatic Arts; and the Ruth and Loring Dodd Playwriting Prize. Just as important to Mashariki, she persuaded Dartmouth administrators to hire a paid staffer to assume the responsibility she and her fellow students had shouldered for planning activities for black stu- dents during the school year.

"I was pooped when I left," she remembers. "But I could go on forever about Dartmouth. If you reached out for something—costumes for a play or a room for an invited speaker—you could get it. I felt really coddled."

Mentors at Dartmouth who encouraged her to aim high have remained valued friends, including former President James Freedman, Dean Sylvia Langford, sociology professor Deborah King and theater professor Mara Sabinson.

Law school may not have seemed her obvious next step and even now, Mashariki, who majored in sociology and minored in drama, struggles some to explain that move. "I knew I wanted to do something creative but didn't know how to get there," she says. As is often the case, peer examples prevailed: Many of her classmates were applying to law school; she followed suit.

After her undergraduate whirl, she studied relentlessly her first year at Harvard. Despite her intention to abstain from the extracurricular activities that had consumed her at Dartmouth, Mashariki worked for professor Cornel West as a teaching assistant for his law school and undergraduate black studies courses and helped the late Judge A. Leon Higgenbotham with research on a racial discrimination case.

"Harvard Law School did a lot for me intellectually. Then I came to Hollywood and really dumbed down," she laughs. Actually, Mashariki's path to Building 38 on the Fox lot was circuitous and bumpy. She earned her J.D. in 1997; a job with a New York City corporate law firm followed graduation, along with marriage to a Harvard classmate. But after three years handling mergers and acquisitions at Proskauer Rose L.L.P., she felt she'd gotten too far away from what made her the happiest.

"I didn't hate being a lawyer," she reflects. "I just didn't love it."

So five years ago Mashariki took another deep breath, this time leaving family and friends behind to enroll in the Peter Stark Producing Program at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. The first year she floundered, a new and miserable experience for her. "I wasn't understanding what a producer does and I felt a lot older than most of the students," she says.

A sympathetic professor introduced her to another student who had written a movie he wanted to make in Africa. The pair raised some money and headed off to Cameroon, Mashariki carrying donated film in her backpack. "I cried so much," she recalls of those two weeks on the other side of the world and way beyond her comfort zone. The mostly Cameroon film-crew members would sooner take orders from white men than from a black woman. They shot in a village with no electricity. Directing the child actors was like herding cats. Without any place to process film they had no idea if their footage was any good.

Mashariki returned to Los Angeles hav- ing learned a lot about what not to do on a movie: Don't write parts for very young children. Don't film in the African countryside. Rewrite the script. Find alternatives. She also came home with a film in the can, her first production: Mboutoukou screened at several festivals and picked up a Student Academy Award nomination from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Fox Searchlight offered her a summer internship and, after that, an offer to become one of the studios eight producers.

Mashariki s strong opinions have made a big impression on studio president Peter Rice. "I remember her first summer," he recalls. "She was engaged in conversation with very senior executives at Fox about movies and it could have been quite intimidating. She didn't necessarily agree with everyone in the room yet she was able to explain herself in a very thoughful and articulate way." She's succeeding as a producer, Rice says, because "she has a great work ethic and taste in movies. I've come to trust her opinion."

Mashariki's job is "to find filmmakers before they become Steven Spielberg," she says. Fox Searchlight bills itself as the independent arm of Twentieth Century Fox Studios, producing what it calls "art-house fare" along with more mainstream pictures. Mashariki works with writers and directors, develops scripts and then lobbies her studio bosses to commit money to these projects. In many ways, she says, "it's like being a lawyer;you're an advocate for your project."

On some films, says Mashariki, "I'm there every step of the way," from pitch meetings to the premier. She shapes the script, decides on casting, watches daily film cuts, directs post-production changes and oversees audience previews and marketing. Her charge is to bring the picture in on budget and compelling enough to make money. On pictures such as In America, the Oscar-nominated 2003 drama about an Irish family struggling to survive in Manhattan, Mashariki had a minimal role because writer-director Jim Sheridan's vision for this autobiographical film so cleanly meshed with hers and the studios.

Mashariki juggles about 15 projects at different stages. Her portfolio now includes a supernatural thriller, a movie about teen runners, a love story filming in Australia and a movie titled Potsdammer Platz about American mobsters in Berlin, penned by Louis Mellis and David Scinto, who wrote Sexy Beast.

More than anything, Mashariki needs to feel passionate about a film and know that the writer and director feel that same excitement and commitment. AntwoneFisher is a good example. The 2002 autobiographical film about a sailor who gains insight into his explosive behavior with the help of a Navy psychologist had been in development for nearly 10 years when she joined Fox Searchlight. Fisher wrote the script based on his best-selling book. Denzel Washington directed—his first effort behind the camera—and starred as the psychologist. Derek Luke played Fisher. Mashariki suggested script changes to strengthen the story and oversaw production —watching dailies to make sure the director got the shots he needed and keeping the project on schedule and within budget. She "loved" working on this project, and even her dad liked the film. "I want to see her doing more of that sort of stuff," he says. A poster from the movie hangs in Mashariki's office along with girlfriend photos and snapshots of a favorite nephew.

The project that grabs her now is October Squall, in which Halle Berry stars and is producing.The story centers on a woman who has a child as a result of being raped, leaves the baby with relatives in her small town and returns years later to save her child after learning he has the same violent impulses as the man who raped her. The film is scheduled for release next year.

This being Hollywood, Mashariki's job comes with its share of perks: yearly trips to the Cannes Film Festival, expense account dinners and glitzy premiers. Cannes may be glorious, but she says screening five to six movies a day, plus the obligatory parties, can be "hellish." One year Mashariki rented a bicycle so she could stretch her legs and finally see a bit of the Riviera. The up side of the festival is that she sees movies before they draw any reviews. "I go in blind, it's just my pure reaction to the film. I like that a lot," she says. Last spring she was particularly impressed by The Motorcycle Diaries, recounting the 1952 journey of young Argentines Alberto Granado and Ernesto "Che" Guevara, who traveled their country on a motorcycle.

Even at home in California the relentless pressure to find the next hot script or sign an A-list director has its burdens. Mashariki is booked for lunch and dinner three months in advance, and she typically spends a good chunk of her weekend "off" time plowing through a half dozen or more of the scripts stacked in her office.

She works this hard because turnover is high. And she's aware that having good instincts helps but doesn't always ensure movie success. "I want to be here in the future," she says. "I have to believe in myself and make good decisions."

Marriage was her one big decision that didn't work, and Mashariki mourns her divorce as her biggest failure. The couple split up two days before the September 11 terrorist attacks and for a time, she worried she would be sad forever. Good friends, her family and tai kwan do, which she still does religiously, helped bring her back.

She also draws strength from the knowledge that she's already inspiring others. Early this year Black Enterprise magazine profiled Mashariki as one of six highachievers to watch. Three months later a stranger came to Mashariki's mother, who now works occasionally as an accountant, for help preparing his tax return. The man said his dream was to go to law school but he didn't know if he had the guts to quit his job and go for it. He was waiting for a sign, he said. Then he mentioned the magazine story he'd read about a woman who left law for her dream of making movies. "Well, here's your sign," her mother beamed.

And dad? "He's proud of me," insists Mashariki. "He doesn't see the tangible benefit of my work to the community, but the community he has fought for has changed. Maybe you're not fighting to get in the door, now you're fighting to stay. I'm in a place my parents never imagined African Americans would be."

And she's likely to stay.

Reversa of Fortune "I didn't hate being a lawyer. I just1 didn't love it," says Mashariki, now a production Searchlight Pictures. in Los Angeles, June2oo4.

MOLLY SELVIN is an editorial writer for the Los Angeles Times.

Ten years after graduation MASHARIKI'S DARTMOUTH YEARS STILL HOLD ENDURING LESSONS IN THE POWER OF FAITH, HARD WORK AND CHANCE.

"Harvard Law School DID A LOT FOR ME INTELLECTUALLY. THEN I CAME TO HOLLYWOOD AND REALLY DUMBED DOWN."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

November | December 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Article

ArticlePresidential Range

November | December 2004 -

Sports

SportsThe Professional

November | December 2004 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

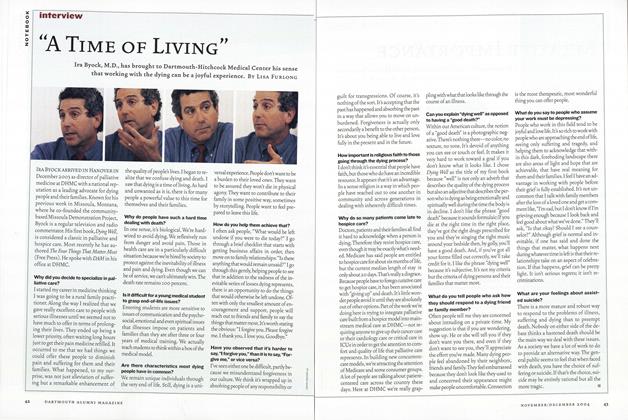

Interview

Interview“A Time of Living”

November | December 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionHarpooning a Liberal

November | December 2004 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

SEEN AND HEARD

SEEN AND HEARDNewsmakers

November | December 2004

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Pros and Cons of Coeducation

FEBRUARY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

September 1975 -

Feature

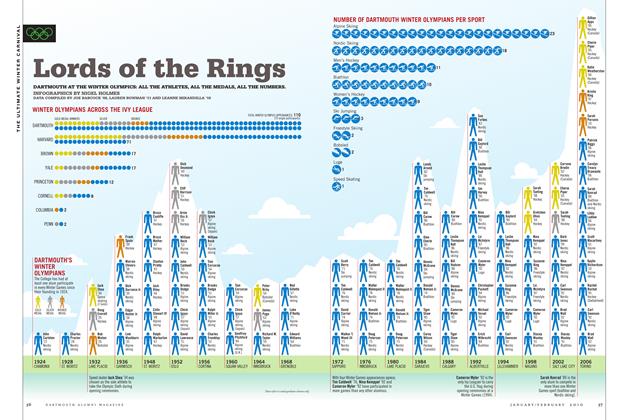

FeatureLords of the Rings

Jan/Feb 2010 -

Feature

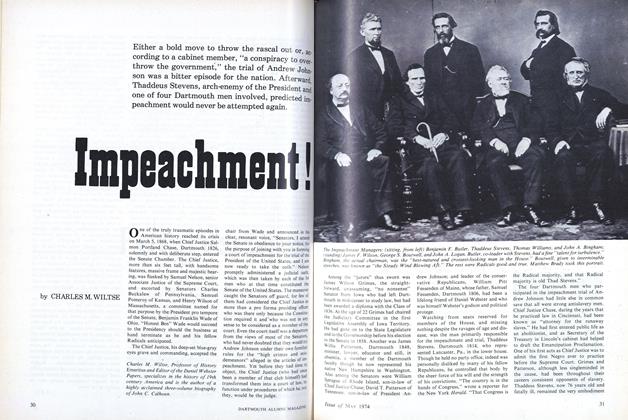

FeatureImpeachment !

May 1974 By CHARLES M. WILTSE -

Features

FeaturesIn the Face of Depression

MAY | JUNE 2025 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May/June 2012 By SPORTING NEWS VIA GETTY IMAGES