The Professional

The trademark style that made Al McGuire a hoops legend was already on display 50 years ago when Dartmouth handed him his first coaching job.

Nov/Dec 2004 Mike O'Connell ’65The trademark style that made Al McGuire a hoops legend was already on display 50 years ago when Dartmouth handed him his first coaching job.

Nov/Dec 2004 Mike O'Connell ’65The trademark style that made Al McGuire a hoops legend was already on display 50 years ago when Dartmouth handed him his first coaching job.

WHEN HE DIED OF LEUKEMIA January 26, 2001, at the age of 72, Al McGuire was remembered as a hardnosed basketball player for St. Johns University, a hatchet man for the NBAs New York Knickerbockers, a madman coach at Belmont Abbey College, a sideline genius at Marquette University and an inimitable TV color commentator. One short but telling chapter of McGuire's life was overlooked: his first coaching assignment, at Dartmouth, where McGuire's uncanny coaching acumen was in evidence early on.

The Dartmouth varsity basketball coach from 1950 until his death in 1957 was the embattled Alvin "Doggie" Julian, a hardscrabble college football coach at Albright and Muhlenberg whose considerable claim to hoops coaching fame was an NCAA national championship at Holy Cross in 1947. Julian parlayed that feat into a head coaching job with the Boston Celtics in the fledgling National Basketball Association. But after two last-place finishes he found job security, if not immediate success, at Dartmouth.

In Hanover it took him four years to field a .500 team. Coming off a 13-13 mark in 1953-54, Julian named former Holy Cross star Joe Mullaney to replace the retiring Chick Evans as freshman coach and varsity assistant. But at the last minute Mullaney had the chance to take the head coaching post at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont. Doggie was in a pinch.

So was McGuire. After three years as an NBA backup player and self-designated brawler, McGuire was reduced to throw-in status in a three-player trade between the Knicks and the Baltimore Bullets, a franchise that folded 14 games into the 1954-55 season. McGuire had no prospects other than to return to bartending at his fathers Irish Town tavern at 108th Street and Roukaway Boulevard, South Queens.

Enter Boston Celtics owner Walter Brown. Brown was still friends with Julian and an admirer of McGuire, who had helped sell out the Boston Garden by claiming he could stop Bob Cousy, the game's greatest backcourt man and the NBAs Mr. Basketball. Brown recommended McGuire to Julian. "Al was top drawer, and a character," remembers Toby Julian '56, the coach's son who was then a junior guard on the Dartmouth team. On November 2 9,1954, penurious Dartmouth athletic director Red Rolfe signed McGuire to a four-month contract calling for what McGuire termed a "Catholic salary" of $2,000. The deal included a bunk in the attic of the Davis Varsity

House, where McGuire later told ValleyNews reporter Jim Kenyon he would sometimes wake up to find fresh snow on his blanket. "Here's Al out of Queens. He thinks he's been put in Alaska," Dave Gavitt '59 told McGuire biographer Joseph Moran.

To the man in the street, McGuire was little more than the trouble-making, poor-shooting kid brother of Knicks backcourt ace "Tricky Dick" McGuire. But to roundball aficionados he was already a cult figure. "When we first heard Al was coming to Dartmouth, we were somewhat starstruck," said Jim Crawford '58, the 6-foot-8 center on McGuire's first freshman squad. "We knew him as the player the Knicks coach [Joe Lapchick] would send in off the bench to hack the devil out of an opposing player. What kind of a coach would this guy turn out to be?"

Those familiar with McGuire's penchant for mischief and mayhem with the Knicks and his hair-trigger temper at Marquette University from 1964 to 1977 maybe surprised at Crawford's answer. "He turned out to be smooth as silk! His decorum on the floor was soft-spoken, articulate, enthusiastic, funny—surprising us with his unique turn of phrase and metaphor, in a New York accent with its street vernacular urging us on—and this in Hanover, New Hampshire, at an Ivy League school."

"He was always very fair, intense, very controlled in his emotions," echoes Crawford's freshman teammate Hal Douglas '58. "It seemed as though he was trying to play down his rep as a tough guy," says McGuire's 1955-56 freshman team captain Mickey Cohen '56. But certain trademarks of McGuire's coaching persona that would mark the rest of his Hall of Fame career could not be concealed or suppressed: his personal magnetism, his insatiable hunger for competition and his visceral feel for the game.

All bony elbows, knobby knees and skinny calves on the court, McGuire was a fashion plate on game days at Dart- mouth, just as he would be during his TV career in the 1980s and 19905. "He was impeccably dressed," remembers Craw- ford. "Dark suit, white shirt, matching tie." His sharp features, curly black hair, wide smile and trim physique made for a striking appearance." He was very handsome. People were drawn to him," says Toby Julian. "I was devoted to him. I loved the guy," says Crawford.

"He was a man's man. Very charismatic, nattily attired, dressed to the nines," says Ron Judson '58, already an All-Ivy pick when McGuire arrived. Yet during scrimmages McGuire would grab Judson's shorts, pull his shirt tail, punch him in the ribs. Coaching both the A and B freshman squads, scrimmaging with the varsity, scouting for Doggie, even skiing on the Hanover golf course slope, were not enough to burn up McGuire's endless energy or quench his competitive fires. He could not resist a murderous 320-mile, twice-weekly commute to the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) State Armory to play and help coach (for peanuts) the semipro Lenox Merchants, a team that from 1954 to 1956 claimed 11 victories in 21 exhibition outings against NBA teams.

Back in Hanover, Judson remembers the spell McGuire cast on his callow fresh- men, who referred to him as "Mr. McGuire." One of Julians traditions was to confine the basketball squads to sleep- ing quarters upstairs in the field house during Winter Carnival weekend. The arrangement meant that the players bunked just below their coach's "apart- ment," where McGuire regaled them with bedtime stories of his NBA days, such as his madcap accounts of the time he played several weeks wearing an iron mask to protect a broken jaw that had been wired shut.

While McGuires freshmen were go- ing 8-2 in 1954-55, the varsity had a break- through season with an 18-7 mark. And things kept getting better. With a class fea- turing such notables as Gavitt and Rudy Larusso '59, McGuires freshmen went 11-2 the following year. Meanwhile, the 18-11 varsity won its first Ivy League title, and then defeated "Hot Rod" Hundley and the West Virginia Mountaineers in overtime in the first round of the NCAA tournament at Madison Square Garden.

There are differing appraisals of McGuire's role as the lone varsity assistant. Larry Blades '57 remembers Julian returning to practice after a sick day to find McGuire leading the team in vigorous calisthenics. "Doggie abruptly stopped what was going on because Doggie didn't believe in that kind of conditioning. Makes the muscles too tight. Somewhat like Doggies belief that if you eat one banana and drink a glass of water you gain five pounds then and there. So the one time I remember Al doing anything with us, Doggie stopped him in his tracks."

YetTobyJulian remembers that "Dad relied on Al a lot. They talked a lot about personnel." Both favored players from the cracked sidewalk neighborhoods of met- ropolitan New York. McGuire later claimed that his recruiting of Larusso and others helped set the table for Julians varsity to go 62-18 and win two more Ivy titles in a three-year stretch from 1957 to 1959. Julian also came to recognize McGuire as an instinctive strategist and endgame master. With Dartmouth trailing by one with 20 seconds to play at the University of Connecticut on December 30,1954, Toby Julian remembers his dad turning to his assistant at the beginning of the final timeout and saying, "Got any ideas?"

McGuire didn't hesitate. "Put Toby in the game," was the first directive. As Toby reported to the scorer's table, the packed house of rabid and knowledgeable fans in the big Storrs arena may have surmised that the coach's second-string son was coming in to take the last shot. But McGuires instructions, imparted without recourse to chalk or clipboard, went something like this: "Get the ball to Toby. Shake it up, scramble some eggs out front. When the defense gets pulled out, Toby finds Fairley in the low post, and Dick goes in for the chippy." No matter that 6-foot-6 Dick Fairley '55 was known more for his tenacious rebounding than for his shooting touch, the cockamamie ploy worked to perfection as Dartmouth scored a 66-65 upset.

"Doggie loved Al," says Gavitt. "They both had a bit of Damon Runyon character in them." But in March of 1956 McGuire left Dartmouth as suddenly as he came. No doubt he missed his wife and two small children left behind in New York, and he was not enamored of playing second fiddle in Alumni Gymnasium. "Al was regarded as a graduate assistant, at most," says Blades. Toby Julian says McGuire "caught hell" for continuing to play with the Lenox Merchants even after being told it was against Ivy League rules. "He had the feeling [the Dartmouth administrators] were watching him closely," Larusso told biographer Moran. "He thought they didn't want this street-smart kid influencing [his players'] values."

So McGuire bartended and sold insurance in New York for a year before accepting a head job at tiny Belmont Abbey near Charlotte, North Carolina. But his influence on his Dartmouth players proved to be indelible. "Al was a gem, a rare cut of diamond," says Gavitt, who went on to coach Providence College to eight straight 20-win seasons. "I cried for him when he won the NCAA championship [at Marquette, in 1997]," says Douglas. "We respected him for his past as a player, for his knowledge of the game and for the way he treated us," says Cohen. Fairley, one of only 12 black students on campus in the early 19505, says, 'Al McGuire brought to Dartmouth a sense, a feeling for diversity" that had been sorely lacking. Crawford, who mentioned McGuire in the last sermon he gave as senior minister of Bostons Old South Church in 2001, calls him "one of the coolest, funniest, shrewdest, most competent coaches of the late-2 oth century."

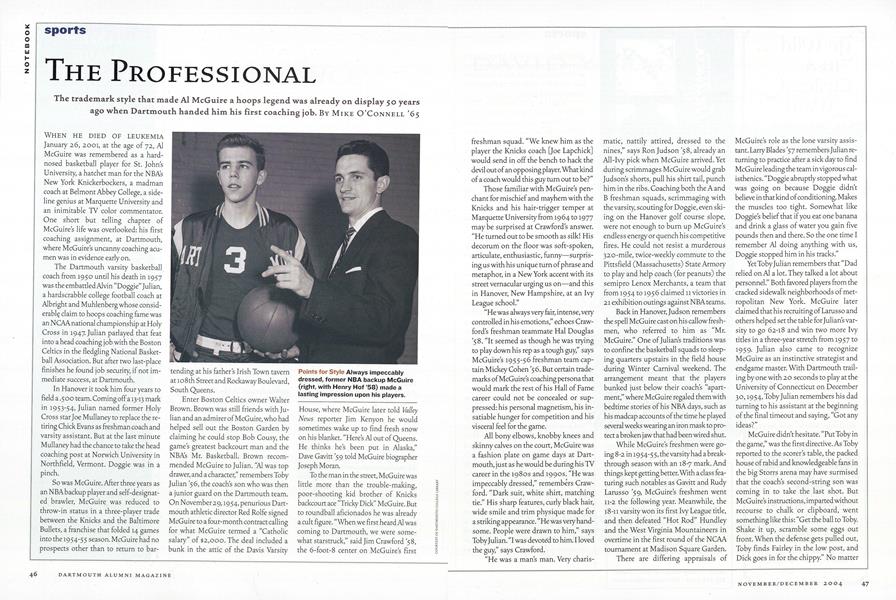

Points for Style Always impeccablydressed, former NBA backup McGuire(right, with Henry Hof '5B) made alasting impression upon his players.

Mike O'Connell is a retired dairy farmerin Baraboo, Wisconsin, where he works as apart-time English teacher for the University ofWisconsin-Baraboo. He played for Julian atDartmouth and coached with McGuire at summer basketball camps in Wisconsin.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

November | December 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

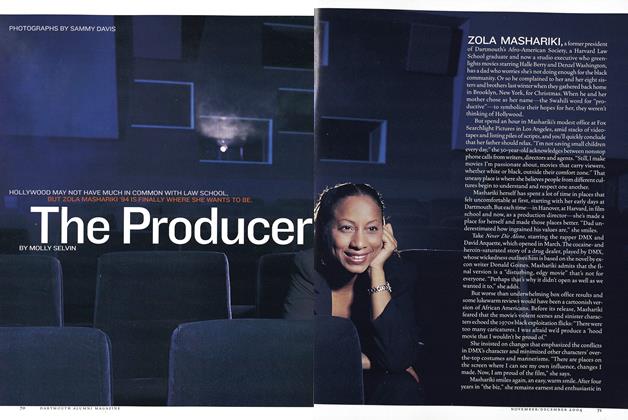

FeatureThe Producer

November | December 2004 By Molly Selvin -

Article

ArticlePresidential Range

November | December 2004 -

Interview

Interview“A Time of Living”

November | December 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionHarpooning a Liberal

November | December 2004 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

SEEN AND HEARD

SEEN AND HEARDNewsmakers

November | December 2004