The College's 16th president discusses alumni engagement, new trustee T.J. Rodgers '70, teaching and research, and more. The first of a two-part interview.

LAST WINTER, DARTMOUTH President Jim Wright issued a report on the first five years of his presidency (www.dartmouth.edu/~fiveyearreport/), a custom for Dartmouth presidents since John Kemeny. In a late-August interview with Bill Jaspersohn '69, associate director of communications for development and alumni relations at Dartmouth, Wright reviewed his tenure to date, discussed his positions on various hot-button topics and outlined his plans for the College in the coming decade.

First things first: Former DartmouthPresident David McLaughlin '54 died onAugust 25. He was a friend and colleague....

And an alumnus Dartmouth is proud of. He strived to make his College better, and lived a life that followed President John Dickeys call that our students make the world a more generous place. I had known him for 25 years and have personally benefited from his insight and encouragement. His life was full but far too short.

What was his legacy at Dartmouth?

He accomplished a great deal, including improving faculty support, expanding the residential system and doubling the endowment. Most important, he played a key role in moving the medical center to Lebanon, which gave academic programs and facilities room to expand. This was second only to coeducation in providing for the Dartmouth of this century. When he left the presidency, he remained active with alumni and gave generously to the College, in both time and wisdom. I'll miss him.

Looking at your own tenure as president, you've had some challenges over the last five years.

We faced the consequences of the economic downturn, which temporarily threw some of our plans off track. We had to deal with the aftermath of 9/11, which had an emotional impact that we didn't quite understand for a time. And we had to come to terms with the awful murders of two colleagues, Half and Susanne Zantop, as well as the deaths of several other faculty members and students. For a time, my role was more pastoral, in the secular sense of trying to bring a community together, than administrative.

Do you think of Dartmouth as a tightcommunity?

I hope it is. Occurrences like those have a way of reminding us what's really important.

Still, you did get a few things done.What's been on your plate?

My focus from the beginning was to strengthen financial aid to guarantee that Dartmouth remains accessible to a wide range of students, and we've done that twice over the last five years. We've provided more support for faculty. We've begun to expand the number of faculty. We've moved ahead with several major facilities— Baker-Berry, Rauner Special Collections, Carson, McCulloch residence hall, the new athletic facilities. We've been preparing for Dartmouth's next capital campaign. And we've continued to provide an educational environment in which students from different backgrounds learn from each other. I'm pleased with that. Diversity is not an end for an institution like ours. It's a means—a means to a better education for all students—and an explicit goal of Dartmouth's since President Hopkins advanced it in the 1920s.

Talk about student satisfaction. How doyou measure it?

I have an open office hour every week and a weekly lunch with a dozen or so students who sign up for it—no agenda, just an opportunity for us to talk about Dartmouth and whether or not their expectations are being met. Over the course of the year, I probably have lunch or dinner with upwards of 250 students. The conversations, I can tell you, are candid. Dartmouth students are pretty direct in sharing their concerns.

For example?

They run the gamut, from a particular course they're taking to the need for more housing to athletics. I hear it all. Mostly, I listen and point them in the right direction if there is someone who can resolve an issue. These conversations let me know what our students are thinking about, what concerns them, what motivates them. Overall, they consider themselves fortunate to be here. And despite the stereotype of young people today being selfish and self-centered, they continue to impress and inspire me with their capacity to give and share. John Sloan Dickey used to say, "The worlds troubles are your troubles." Our students take that to heart.

You've made diversity a priority at Dartmouth. Critics—some of them vocal-have said you're "social engineering."How do you answer that?

I'm not an engineer, social or other. I'm a historian and a teacher. Diversity is about education. I tell students I have no interest in determining who their friends are, who they should hang out with. In fact, I tell them they shouldn't be concerned if they spend their time with students who are most like them. Life here can be stressful, and there's nothing wrong with seeking out people who share your interests— in music, books, sports, politics, whatever. But I also tell them that it's hard to learn if all of our attitudes and tastes are reflected back and reinforced. This is a place of learning, and I want to make it hard for students to spend four years here and not encounter difference. But nothing is engineered for them—they're regularly encountering differences on their own.

What about economic diversity—aridthe kind of students Dartmouth is tryingto attract?

Dartmouth has historically been committed to recruiting students who don't fit a stereotype of what constitutes an "Ivy League" student. Dartmouth was a place where hill-country farm boys, including Daniel Webster, came from New Hampshire and Vermont to receive an.education. The record is writ large of what those young men went on to accomplish. In the 1920s, under President Ernest Martin Hopkins, himself a financial aid student, Dartmouth made a commitment to the principle that students learn from other students and that we're not socially and culturally homogeneous. In the 1930s and 1940s Dartmouth provided opportunities for lower-middle-class and working- class kids from Massachusetts and New York when such was not common. The critical problem that schools like Dart- mouth face is trying to encourage families of modest means to imagine that their student could come here, that our financial aid system would enable them to do so. We need to do better, although the economic diversity of our student body today is compelling. The percentage of first-generation college students is about 16 percent. As a first-generation college graduate myself, I'm proud of our record.

Dartmouth alumni are smart, engagedand energetic. Many of them want to bemore involved in Dartmouth's business.Can they?

Right now, I don't think we have a sufficient means of interaction with alumni. The Alumni Council was set up almost 100 years ago for that purpose, and I and my senior staff meet with councilors when they're in town. It's an opportunity for us to tell them what's happening up here and to hear from them about the issues that continue to define Dartmouth. It's important engagement, but we need to find additional ways to both inform and take advantage of their professional expertise. This is a work-in-progress. We can only become stronger by taking full advantage of alumni commitment to Dartmouth.

One of Dartmouth's newest trustees,T.J. Rodgers, has received a lot of attention for his views and his write-incandidacy. Could you talk about him andthe impact he might have on the board?

Well, we start with a pretty good common base. We both have a tremendous affection for this institution and for the wellbeing of Dartmouth students. When I called to congratulate him after his election, I pointed out another piece of common ground we share: We're both pretty committed Green Bay Packers fans.

A pair of cheese heads!

[Laughs] I don't know if he wears a cheese head. I haven't yet, but you can see my Packers coffee mug across the room. I'm a Wisconsin guy, as is he. I look forward to working with him. This is an extremely bright and accomplished man who cares about Dartmouth and wants to contribute. I intend to find ways he can do that. Do we have different views on some issues? I think we do, but we haven't explored those yet. I'm open to hearing what he has to say and to responding to his concerns. We can surely do many things better. I have every confidence he'll be open to hearing what it is that we're doing.

I'm guessing that Rodgers isn't the firsttrustee you've encountered with viewsdifferent from your own.

True. The board represents a range of views and attitudes. This is no monolithic body. What is common to this board— and T.J. will add to it—is a tremendous commitment to making certain Dartmouth continues to be strong. That's what binds us.

You've called Dartmouth "a university inall but name." Some alumni fear thatthat means changing the College's corecommitment to undergraduate learning.Does it?

I think we are a university in all but name. We have the fourth oldest medical school in the country, the oldest business school, the oldest engineering school. We've had graduate programs since the 1790s. But Dartmouth still proudly calls itself a college. President McLaughlin used to say that Dartmouth was a university that was good enough to call itself a college. I am committed to our providing the finest undergraduate experience in the country. There aren't many universities that would pursue that idea as a priority, but historically it's what has defined Dartmouth.

How do you respond to the view thatDartmouth should not be in the researchgame, that teaching and research are atodds?

Those who imagine that Dartmouth would be Dartmouth if its faculty were not doing research, and simply reading from yellowed lecture notes, are wrong. Anybody who thinks we could recruit the sort of students who come to Dartmouth, both today or those who came here 50 years ago, and not have faculty who excite them with the passion and freshness of their own discoveries— respectfully, they are also wrong. You can have researchers who don't teach, and there's a place for them—but not at Dartmouth. We do both here. I did both for years—I taught a lot of Dartmouth students while carrying on my own research in history and carrying that back into the classroom. Research feeds teaching. And believe me, students with their questions and insights feed the research.

You've written, "The protection and enhancement of the Dartmouth experience is my central goal and will remainmy mission going forward." What exactly are you protecting and enhancing?

A sense of community;—belonging to a group larger than one's self that encourages you to be the best you can be. That has historically marked Dartmouth, and it's what attracted me35years ago,whenI first came to Hanover. I often tell parents and students that students have to compete mightily to come to Dartmouth, but they don't have to compete to be here. We focus on collaboration, something that's not common at all institutions. The Dartmouth experience also means students and faculty developing close relationships as mentors and friends as well as teachers. Finally, of course, it's the place. We have an obligation to protect the integrity of this place physically. In this complicated world today, I think protecting and advancing those values is more, not less, important.

What is Dartmouth's biggest challengeover the next five years?

Our biggest challenge is competing for students and recruiting faculty. You can never stand pat at a place like this. We're not as wealthy as those schools that outrank us in U.S. News & World Report.We do well. We're not poor. But we must continue to use our resources wisely. We have facilities that need to be built, faculty to recruit, programs to fund. If we focus on the quality of experience our students have—if we stay on purpose—we'll make the right choices.

In the next issue: Jim Wright on fraternities, freespeech and Dartmouth's most ambitious fundraising campaign ever.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

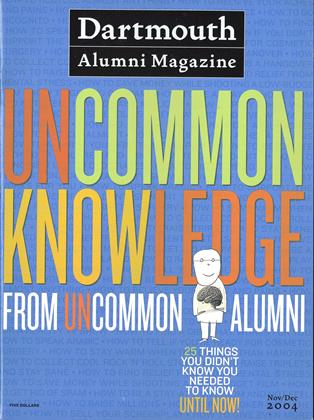

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

November | December 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

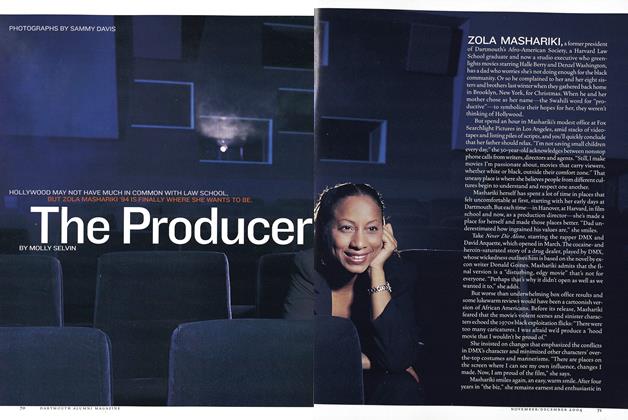

FeatureThe Producer

November | December 2004 By Molly Selvin -

Sports

SportsThe Professional

November | December 2004 By Mike O'Connell ’65 -

Interview

Interview“A Time of Living”

November | December 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionHarpooning a Liberal

November | December 2004 By Dinesh D’Souza ’83 -

SEEN AND HEARD

SEEN AND HEARDNewsmakers

November | December 2004