Saturate, Don’t Isolate

U.S. policy toward North Korea needs to recognize Kim Jong-Il’s security concerns.

Mar/Apr 2004 David C. KangU.S. policy toward North Korea needs to recognize Kim Jong-Il’s security concerns.

Mar/Apr 2004 David C. KangU.S. policy toward North Korea needs to recognize Kim Jong-il's security concerns.

THE NORTH KOREAN REGIME IS A reprehensible and brutal dictatorship. It has engaged in massive human rights abuses and allowed many of its own citizens to starve through its foolish economic policies while exporting its weapons technology to anyone with enough money to purchase it. The revelations last year that North Korea has a secret nuclear weapons program has once again created a crisis between the United States and North Korea. Everyone would like to see the regime disappear or at least modify its policies and join the community of nations. The current debate over North Korea is not about this goal, but rather about the strategies the United States should follow toward this goal.

With both the United States and North Korea putting forth proposals that would essentially trade the latter s nuclear weapons program for security assurances, there exists the chance for a temporary solution to the current crisis on the Korean peninsula. The situation is exacerbated by the proximity of Russia, China and Japan, each of which shares a border with the Korean peninsula, and each of which has different goals and interests in the outcome. Given the potential volatility of the area, the Bush administration is right to ease pressure on the North Korean regime, but there is an overriding problem: The United States lacks a long-range strategy to resolve the peninsulas tensions.

Because the United States refuses to give security assurances to North Korea until it proves it has dismantled its weapons program and North Korea refuses to disarm until it has security guarantees from the United States, a stalemate exists.

Even countries such as North Korea can have security concerns. Without movement toward resolving the security fears of the North, progress in resolving the nuclear weapons issue will be stalled. Lurching from crisis to crisis as the United States has done previously is not a long-term strategy for the country. For more than a decade we have been expecting North Korea to collapse and yet it has survived. Indeed, North Korea under Kim Jong-il may survive for another 20 or 30 years.

A long-term strategy must focus either on violent change or peaceful change. The risks of promoting violent change are very high. Fifty years of successful deterrence show that we can contain the North Korean threat. But a strategy of economic engagement that saturates North Korean citizens with capitalist ideas and slowly changes their mindset while raising their living standards is the best strategy for the United States to pursue.

If North Korea really wanted to develop nuclear weapons it would have done so long ago. Above all, the regime wants better ties with the United States. The policy that follows from this is clear: The United States should begin negotiating a nonaggression pact with the North. It should let other countries such as South Korea and Japan pursue economic diplomacy if they wish. Until

December 2002, International Atomic Energy Agency nuclear inspectors had been in the country for a decade. If the North allows back U.N. inspectors and dismantles its reactors, the United States could then move forward to actual engagement. But to dismiss the country's security fears is to miss the cause of its actions.

North Korea does have reason to be afraid of the United States. Because the 1953 armistice between the two countries was never replaced with a peace treaty, the United States and North Korea are still technically at war.

In 1994 the two countries resolved a previous nuclear crisis with a framework designed to trade the North's nuclear program for alternate energy sources and, ultimately, diplomatic recognition from the United States. Although this 1994 Agreed Framework was a process by which both sides set out to slowly build a sense of trust, both sides began hedging their bets very early in that process. Since neither side fulfilled many of the steps even during the Clinton administration, the framework was essentially dead long before last year's nuclear revelations.

The accepted wisdom in the United States is that North Korea abrogated the framework by restarting its nuclear weapons program, but both the Clinton and Bush administrations also violated the letter and the spirit of the agreement.

In 1994 the United States promised under the framework to help North Korea build lightwater reactors that could not be used to make nuclear bombs; these reactors were to come on line in 2003. By 1998 the United States already had second thoughts, and slowed its efforts to the point that the reactors are at least five years behind schedule. The United States also promised written assurances that it would not use nuclear weapons against North Korea, but the Bush administration's 2002 Nuclear Posture Review targeted the country. The reference to North Korea as part of an "axis of evil" made it clear that the Bush administration does not trust the North.

For the framework to work would require enthusiasm expressed by both parties. The collapse of the framework is disappointing because North Korea is actively seeking accommodation with the international community.

In 1992 North Korea was the most closed society in the world. Since then it has abandoned its centrally planned economy and now allows supply and demand to set prices. North Korea has been restructuring its nascent financial sector, and this includes consolidating a number of smaller banks into one larger commerical bank, Shintaek Unhaeng. South Korea has rapidly increased its relations with the North: South-North trade was $340 million in the first six months of 2003, and trucks on a road that goes through the DMZ carried some of that trade. More than 100,000 South Koreans have visited North Korea in the last two years. Furthermore, there is currently $1 billion in U.S. currency in circulation in North Korea. To cap all of these developments, Kim Jong-il finally admitted last September—after three decades of denials—that the North kidnapped Japanese citizens in the 1970s. The United States should encourage these trends and such candor, not retard them with a policy of pressure and isolation.

Focusing on economic change is the best strategy for the United States because it is transforming, gradual and peaceful. When capitalism is unleashed, it is very difficult to turn it back. Give North Koreans a taste of economic freedoms and outside ideas and the next generation will view their own leadership and the outside world in different terms. Engagement is also gradual, and allows us to bring North Korea slowly back into the world. Economic transformation is also peaceful. Our quarrel is not with the people ple of North Korea: They are the victims of a brutal and repressive regime.

There is widespread skepticism that North Korea either wants to reform or can reform without having total collapse first. Kim Jong-il will never relinquish power, but the United States should be more concerned with affecting the younger generation of North Koreans who will matter after Kim passes away. The United States could choose to isolate the North for another two decades. As has been shown, isolation and coercion have little effect on the regime, and it puts the United States in a reactive mode. As to whether any reform is possible, moving the North along the path toward capitalism—even if it will provoke an economic collapse at some point before real growth can occur—is still a policy that will ultimately benefit North Korea and the United States. More importantly, internal collapse that comes because North Korean citizens are becoming capitalists is better than forcing regime change that could prompt a nationalistic backlash.

The Soviet Union and China ultimately changed not through actual war but because their systems could not keep up with the dynamism of the West. Don't forget that it was President Nixon who first engaged China, not the other way around. Furthermore, China did not make an instant transition to capitalism in 1978. Chinas opening to the world has been a decades-long process of gradual reform and opening, but it has also been successful beyond anyone's hopes. The United States engaged these nations precisely to moderate the potential for conflict and in order to expose their citizens to capitalism and democratic ideas.

We may have no choice but to live with Kim Jong-il's North Korea for another 20 years. If that is the case, facilitating market reforms in North Korea is both the most effective—and most humane—strategy for the United States to pursue.

Our quarrel is not with the people of North Korea: They are the Victimsof a brutal and repressive regime.

DAVID C. KAN G, associate professor of government,teaches also at Tuck School of Business.He is the author, with Victor D. Cha, of Nuclear North Korea: A Debate on Engagment Strategies, published last fall byColumbia University Press.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA is for Abundance

March | April 2004 By RICK GREEN -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

March | April 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

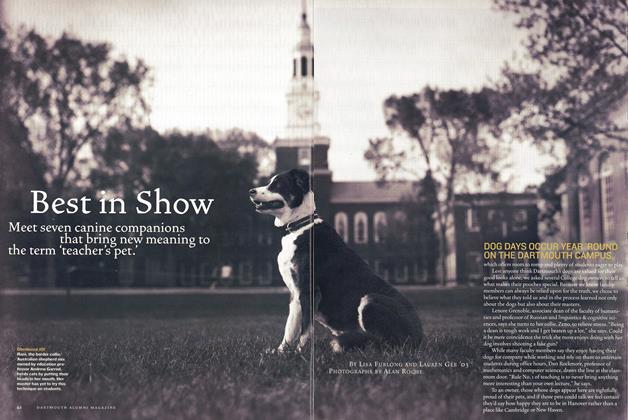

Feature

FeatureBest in Show

March | April 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

From the Dean

From the DeanThe Fourth ‘R’

March | April 2004 By Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEAnimal Attraction

March | April 2004 By Ted Levin

Faculty Opinion

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONInvestor’s Ed

Nov/Dec 2006 By Annamaria Lusardi and Alberto Alesina -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONThe Perils of Innovation

Nov/Dec 2010 By Chris Trimble and Vijay Govindarajan -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Next Frontier

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jay C. Buckey Jr. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONShiny Bubble

May/June 2005 By JOHN H. VOGEL JR. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July/August 2006 By Lucas Swaine -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMyths of Innovation

Mar/Apr 2006 By Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble