The Fourth ‘R’

Research is not a distraction from our mission but an essential part of a great teaching institution.

Mar/Apr 2004 Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61Research is not a distraction from our mission but an essential part of a great teaching institution.

Mar/Apr 2004 Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61Research is not a distraction from our mission but an essential part of a great teaching institution.

AT HOMECOMING WEEKEND this past October, prior to the big game, 24 undergraduate students presented posters at the Top of the Hop on the research they were doing under the direction of professors from the humanities, sciences and social sciences. The excitement in the room was palpable, and every alumnus there beamed with pride.

What was so exciting about this event? It was the sense that students at Dartmouth are not just learning, they are learning how to discover, invent and dig deeperto look beyond what's known and venture into what's next. Yes, research is alive and well in Hanover. The students want it, the professors do it and the synergy is exciting.

And yet the fact that research is thriving at Dartmouth seems to be a well- kept secret. Why? Each higher learning institution, especially within the Ivy League, has a brand name that carries specific associations about the school's strengths and weaknesses. Dartmouth has been commonly touted as a teaching—not a research —institution. This may have been true at one time, but institutions evolve, usually in synchrony with the overarching cultural events of the times, and Dartmouth is no exception.

We sometimes long for the simpler past, even though we are very much committed to the future. In my travels to meet alumni and talk about current work and future goals at Dartmouth, I have encountered alumni who are concerned about the notion of focusing on research at Dartmouth. I try to assure them that not only have times changed for the better and that being known for cutting-edge research is crucial for a higher learning institution, but that it is simply wrong to think focusing on research damages rather than enhances our reputation as a teaching institution. Given that we are demonstrably both, we should not maintain the fiction that we merely teach in order to conform to a dated image of Dartmouth.

We can look deeper than a student poster session for proof that Dartmouth is committed to research. The Dartmouth teaching load is similar to that of professors at Yale, Harvard and the other Ivies and lower than the load at state colleges.

When a proposal was put forth here a few years ago to have professors teach more, the faculty wisely rejected it out of hand. The reason: If the faculty is to maintain an involvement in the intellectual topics they have chosen to study they must do research on that subject. To conduct that research, they must have time. While it is obvious that research is part of the fabric of scientific enterprise, it is also true for the social sciences and humanities. Even the per- forming arts undergo radical experimentation and change. To be on the cutting edge of any field, there must be time to devote to research, and that means balancing teaching load with research time. Our faculty know this.

One reason we may be reluctant to fully embrace the reality of Dartmouth as a research institution is the false belief that time devoted to research detracts from teachers being great, especially at a great teaching institution. On the contrary; research enhances teaching. Teaching alone—in the sense of purely conveying what is known—is, as the famous psychologist B.F. Skinner wrote in his novel Walden Two, "only passing the buck." Great teaching is the process of not only communicating the current knowledge of the field, but also leaving the student with an unease about the status of that knowledge. Great teaching is communicating the dynamic nature of how we humans understand the world. The goal of great teaching is to impart to students the imperative to "keep digging." Great teaching requires a faculty that is involved in current research.

Todays undergraduates are not any smarter than any other students who have attended Dartmouth, but they know different things. I like to use an example from biology. When I graduated from Dartmouth in 1961 the role of DNA as the genetic code had only been discovered a few years earlier. While we knew about it, we spent most of our time dissecting fetal pigs, learning the names of animals and plants and only just beginning to study genetics from a molecular basis. Today the students arrive from high school with more knowledge about biology than was known by the human race just 40 years ago. Many of them have already done restriction enzyme experiments and are poised to plunge more deeply into the new biology.

When freshmen arrive at Dartmouth and are interested in biology, they can be placed immediately into world-class labs doing cutting-edge research. Professor Victor Ambros, for example, who just won the prestigious Newcomb Prize from Science magazine, recently identified a new class of genes that encode what are called micro-RNAs. These micro-RNAs are very short and do not code for proteins, a reason they had been missed in all of the genome-sequencing projects to date. Because these new genes can be found in many species of animals, it is believed they must have an important function. Ambros and professor of biology Ed Berger are researching the function of these new genes; it appears there are some elegant developmental mutations associated with the loss of several specific micro-RNA genes. This is dazzling and important work—and our undergraduates are in on it at an early stage.

There is a belief out there that research is the purview mainly of science; sometimes we seem hesitant to tout ourselves as a research institution because we don't want our reputation as a leading humanities school to suffer. This, too, is a myth. Professor Susan Ackerman 'BO, in an offcampus program I visited recently in Edinburgh, delved into the history of the expansion of Christian thought throughout Greece and Central Europe up to its introduction to England. Ackerman's own research seeks to illuminate the ways in which early Judaism interacted with the religions of the Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Canaanite worlds. Her findings add a richness and mystery to those early days of Christianity and reveal that what we think we "know" can always be challenged.

We do need to provide high-quality- teaching for this generation. And the highest quality teaching depends on our faculty knowing the latest information to teach—and on teaching students to push the boundaries of what is known. How can this be done by professors who are not themselves intimately involved with the discovery process?

So here is the truth: Dartmouth is not the Ivy that values teaching over research. Dartmouth is, and must lay claim to being, a great teaching institution because we insist that our teachers are equally dedicated to research. This understanding of what makes great teaching is taking hold everywhere. At research institutions such as the University of California, professors are now held accountable for the quality of their teaching. At Dartmouth we hold our great teachers accountable for a higher standard of research: Research that is important, research that is an essential part of teaching.

Michael Gazzaniga

MICHAEL S. GAZZANIGA is dean of thefaculty and director of Dartmouth's cognitiveneuroscience program.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

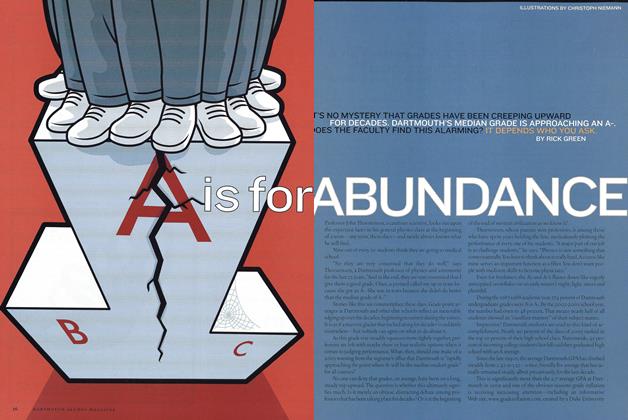

Cover Story

Cover StoryA is for Abundance

March | April 2004 By RICK GREEN -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

March | April 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

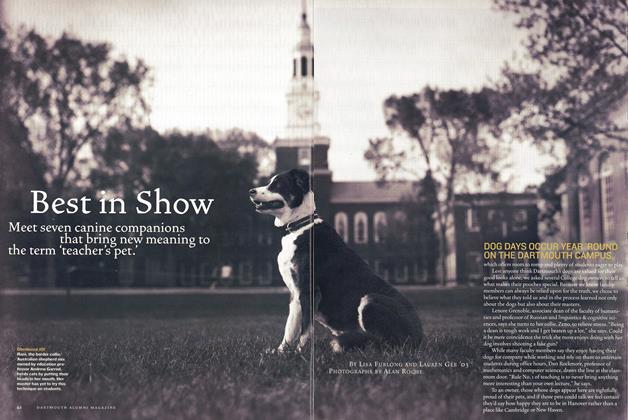

FeatureBest in Show

March | April 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

March | April 2004 By David C. Kang -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEAnimal Attraction

March | April 2004 By Ted Levin