FROM TWO SMALL OFFICES IN Fairchild Hall—and an adjacent computer lab shared with the earth sciences and environmental studies departments- researcher Bob Brakenridge and his team at the Dartmouth Flood Observatory monitor the globe for high water. They do this by downloading satellite images of the earths surface that can be searched in segments of 10 degrees longitude by 10 degrees latitude, roughly 750,000 square miles.

This is not merely an academic exercise. The observatory's Web site and atlas of archival data are authoritative sources for everyone from Third World government officials wondering if they have stranded villagers to relief workers wanting to deploy aid; from those contemplating construction in floodplains to insurance companies trying to determine if underwriting those properties is a sound investment. Then, of course, there are the college students from across the country who visit the observatory Web site www.dartmouth.edu/~floods as part of their curricula.

The practical applications of Brakenridge's work are what makes his job worth- while. "It's satisfying to do something useful rather than write an article that sits in a bound volume in a library," he says.

Established in 1991, the observatory has been funded primarily by successive three-year, $300,000-plus grants from NASA, the most recent of which expires this spring. While NATO has underwritten supervision of a grant applied for in concert with Hungary and Romania, and there is lesser funding for specific projects, Brakenridge does have concerns about his budget, um, drying up. "I worry that if I move on, this will end," he says.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

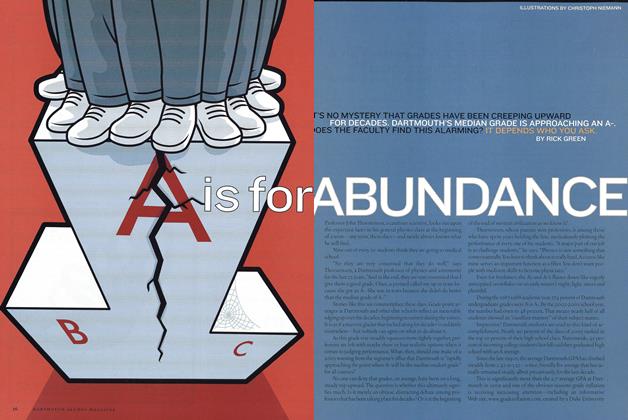

Cover StoryA is for Abundance

March | April 2004 By RICK GREEN -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

March | April 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

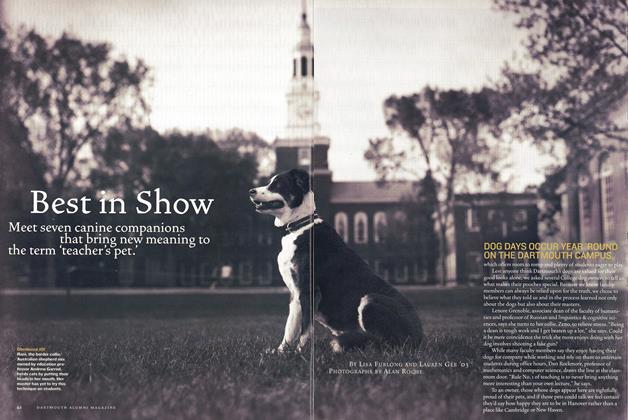

FeatureBest in Show

March | April 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

March | April 2004 By David C. Kang -

From the Dean

From the DeanThe Fourth ‘R’

March | April 2004 By Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61

Article

-

Article

ArticleThird Composer for Summer.

MARCH 1967 -

Article

ArticleUniversity Press

MARCH 1971 -

Article

ArticleNorthern N. E. Art Show

JULY 1973 -

Article

ArticleBut the Mainers Need English as a Second Language

JUNE 1996 -

Article

ArticleSeattle

MARCH 1969 By THOMAS B. RUSSELL '61 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

February 1952 By William P. Kimball '29