Canoes Undying

Could the canoe be the most recognized, enduring symbol of the College?

Jul/Aug 2004 JIM COLLINS ’84Could the canoe be the most recognized, enduring symbol of the College?

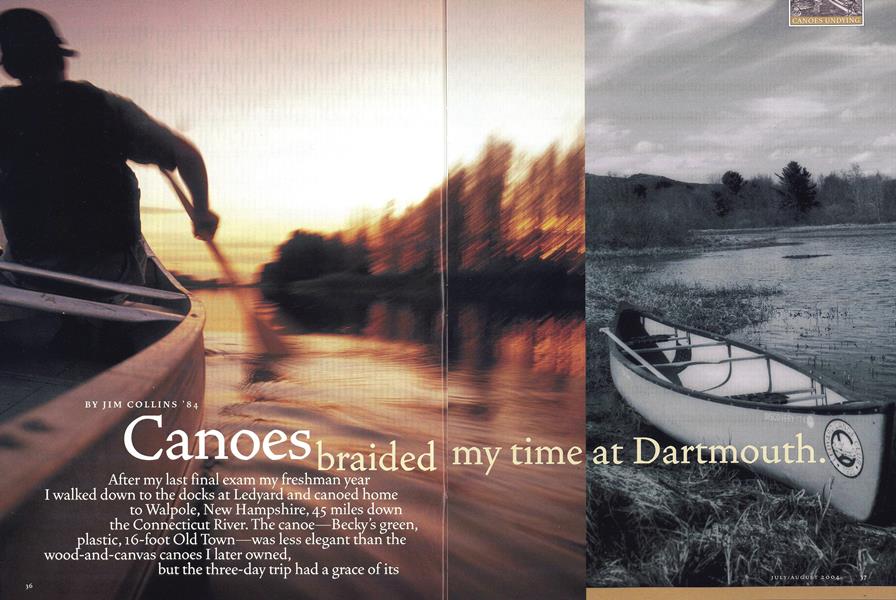

Jul/Aug 2004 JIM COLLINS ’84After my last final exam my freshman year I walked down to the docks at Ledyard and canoed home to Walpole, New Hampshire, 45 miles down the Connecticut River. The canoe—Beckys green, plastic, 16-foot Old Town—was less elegant than the wood-and-canvas canoes I later owned, but the three-day trip had a grace of its own. Returning by water from my first year in college felt triumphant. It evoked the style of John Ledyard's legendary departure from Dartmouth in 1773 (which of course we knew about). It gave a rhythm to the breathing space between school and summer work, and I fell in love, besides.

During my sophomore summer a set of lifetime friendships was cemented by starry nights, northern lights and battered Grumman aluminum canoes at DOC cabins on Reservoir Pond and Lake Arming- ton. (Five yeats later, Bob Barrett '82, Elliott Gimble '84 and I would paddle downriver from Littleton to Hanover. We rafted our canoes together and floated the last seven or eight miles to Titcomb Island, letting the farewell broadcast of A Prairie Home Companion drift over us from a portable radio. The next morning, dirty and unshaven, we ate doughnuts at Lous while the rest of the campus listened to Senator Bill Bradley give commencement advice to the graduating seniors.)

A few weeks before my own graduation I paddled in a flotilla of canoes, most of them Mad River "Explorer" models made of ABS plastic, down the wild upper half of the Connecticut in the special "Source to Sea" trip that helped celebrate the Outing Clubs 75th anniversary. We bushwhacked one of the canoes three-quarters of a mile through brushy woods up to the tiny Fourth Connecticut "Lake" that marked the headwaters and ceremonially dipped the boat into the water while 20 pairs of hands touched gunwales and officially started us on our way. The memories remain vivid all these years later: overnighting in a barn in Lancaster with the rain pouring down outside while we ate take-out pizza and waited for our gear to dry at the local laundromat; watching Walker Weed '40 and his son, Teyck '71, effortlessly pull ahead of the rest of us, day after day, the two of them as smooth and synchronized as any paddlers I've ever seen; getting up before dawn with Dave Hooke '84 and power-stroking the 15 miles from Orford to Hanover so Hooke could get back for a 9 a.m. appointment.

My life's course was changed on that trip. I stepped ashore at Ledyard having decided to defer my.acceptance to business school and, instead, look for a job with the Appalachian Mountain Club in the White Mountains. A few years later I was living in a cabin on an island in southwest New Hampshire, I'd found work that I loved, close to home, without the benefit of B-school. During the warm-weather months I paddled to shore in a beat-up canoe I had bought from the Ledyard Canoe Club during one of its end-ofspring-term sales. It still has the club decal on the bow.

BUT THIS ISN'T MEANT TO BE A PERSONAL ESSAY. I'm thinking, now, not about the stories, so much, but about the general reaction I've received in telling them over the years. "Of course you canoed home from Dartmouth!" more than one person has said, as if that's what Dartmouth students do all the time. "You bushwhacked a canoe almost a mile just to touch it in the headwaters?" others have said. "That's perfect."

And it is perfect—there's something about the intersection of a North Country setting with the importance of ritual and a group of slightly crazy, go-for-it college students that seems peculiar to Dartmouth. A canoe at the center of the intersection seems perfectly natural. The same story.involving Middlebury students wouldn't carry half the resonance, and substituting M.I.T. or Yale would be so incongruous as to make it almost a joke.

At Dartmouth, though, that kind of story is part of such a long tradition that it's almost unremarkable. And it touches one of the reasons, I think, that the canoe is a recognized, enduring symbol of the College. Perhaps the most fitting symbol we have.

Dartmouth claims the oldest and largest collegiate canoe club in the country, one that has displayed a certain spirit from the very beginning, from gunwale-bobbing contests to smuggling canoes during Prohibition across the Canadian border under the cover of Champlain darkness. "Left Wells River at 8 this morning + took our time...," reads a logbook entry from the old Johnny Johnson Cabin up near the mouth of the Ompompanoosuc, "...chasing wood ducks around the fields with a revolver. River quite high and many hayfields underwater. Stopped in here for supper." Traditions of weekly moonlight paddles and sunrise pancake feeds continue to this day. How many schools have an annual 215-mile canoe trip? (The "Trip to the Sea," from Hanover to Long Island Sound, started in the 1920s. In 1960 Pete Knight '62 and Jon Fairbank '62 won a five-school race over that distance in an incredible 33 hours, 50 minutes, a record that has stood unchallenged since. Today the trip is notable for its tradition of paddling nude past the Hartford, Connecticut, skyline.) Who else but Dartmouth students would portage two canoes across the peaks of New Hampshire's Presidential Range in honor of the nation's bicentennial? Or get married in a floating, flower-bedecked, 15-person war canoe? Where else would you find downhill canoe races at a Winter Carnival?

In The Singing Wilderness, Sigurd Olson captured that brand ofspirit with a passage I came to memorize—one, I might add, thatincludes young women today:

"Only fools run rapids, say the Indians, but I know this:As long as thereare young men with the light of adventure in their eyes and a touch of wildness in their souls, rapids will be run. And when I hear tales of smashed canoes and lives as well, though Ijoin in the chorus of condemnation of the foolswho take such chances, deep in my heart I understand and bid them bon voyage....The elements of chance and danger are wonderful and frightening toexperience and, though I bemoan the recklessness of youth, Iwonderwhat theworld would be like without it. I know it is wrong, but I am for the spirit thatmakes young men do the things they do. I am for the glory that they know."

AT DARTMOUTH THAT SPIRIT REACHES DEEPER THAN youthful recklessness. It's the spirit that drove the ambitious, logistically complicated, student-organized canoe trip down 1,685 miles of Danube River in 1964, back when the Iron Curtain was closed to virtually all outsiders. That's one trip among hundreds: Ledyard canoeists have sought out wilderness water all over the globe, most recently in long trips in northern Quebec and the Northwest Territories. What value can you place on such an education in geography and self-reliance? The same spirit has created Olympic canoeists, nationally ranked white-water paddlers, wilderness camp leaders and registered guides. In 1988 Ledyard hosted the National Marathon Canoe Championships, then hosted them again in the summer of 2002—the only two times the nationals have been held in New England.

Symbols, of course, go beyond spirit. They lodge in the subconscious because they represent something true, they distill meaning because they feel right.

The exploits of the Ledyard Canoe Club dovetailed perfectly with the emerging national reputation of Dartmouth in the 20th century. Fox Films, Life magazine and National Geographic, among others, publicized Dartmouth's outdoorsy image in feature films and articles, an image reinforced by the vigorous "still-north," "hillwinds" song lyrics of Richard Hovey, class of 1895; years of iconic photography by College photographer Adrian Bouchard '41; and by Dartmouth's outdoors-loving president John Sloan Dickey '29.

The hiring of legendary Maine guide Ross McKenney as "woodcraft advisor" in 1937 introduced a lineage that stretched back to the wild, log-driving days of the turn of the 20th century. Ross introduced "his boys" to the Allagash and other storied waterways of northern New England. He taught them how to maneuver a canoe through heavy water, how to portage efficiently, how to swing a paddle all day without getting tired. He organized the first intercollegiate "Woodsmen's Weekend," which included one- and two- man canoe races among its events at Storrs Pond. Dartmouth dominated the first decade of competitions. McKenney put Dartmouth in its place; he linked the College and its education with the heritage and traditions of its rural North Country setting.

An important part of that heritage predated even John Ledyards theatrical exit from the College. The canoe is a Native American invention. When Eleazar Wheelock founded his missionary school in the wilds of New Hampshire in 1769, he located it in the middle of a still-active Abenaki culture. The Abenakis had used the river for centuries, traveling by canoe among seasonal settlements and hunting grounds. One large settlement, called "Coos" or "Cowass," was located on the giant oxbow above Hanover near present-day Newbury, Vermont, and Haverhill, New Hampshire. By the time Wheelock arrived, their birchbark canoes—the bark skins pulled tight and lashed over marvelously flexible white cedar hullshad fully evolved into refined, beautiful, functional watercraft. Abenaki and Montagnais canoes started transporting furs down the Connecticut River in 1690, to trading posts as far south as present-day Agawam, Massachusetts. As English settlements advanced into the Upper Valley and as the beavers were trapped out, though, the fur trade dwindled. It was gone altogether by 1800.

By then Native tribes had been sharing the waterway for some time. The first log drive on the Connecticut—81 large white pine logs destined for masts in the British Navy—rumbled downriver eight years before Dartmouth's charter was drafted. Rafts and barges floated past the College in subsequent decades, carrying exports of lumber, charcoal and potash to Hartford and Long Island Sound. Until the late 1840s, when rail lines finally stretched into central and northern New England, the river remained an important transportation link. Log drives choked the river each spring and summer until 1930, with millions of board-feet of sawlogs and pulp headed for mills in Holyoke and Turners Falls, Massachusetts. Robert Pike '25 wrote a definitive account of the drives in his book Spiked Boots.

In the mid-19th century another part of the heritage rippled outward, this one from the great Adirondack forest of upstate New York. In 1858 a group of 10 Boston-area intellectuals spent two weeks camping, canoeing and exploring Follensby Pond, a pristine, remote lake of a thousand acres. The so-called "Philosophers' Camp" included Ralph Waldo Emerson, poet James Russell Lowell, naturalist Louis Agassiz and Oliver Wendell Holmes' brother, John. The rustic gathering, celebrated in painting and poetry, found renewal and recreation in nature—and launched an Adirondack tradition of backwoods preserves and hunting and fishing clubs, many of which became private playgrounds for Eastern academics and literati. So many Ivy League professors summered at Blue Mountain Lake that some called it "Princeton North."

The canoe was the vehicle of choice for both upper-class pleasure and nature excursions. Writers from The Atlantic and Harper's were part of the evangelical crowd that spread the word to the wider world. Professors brought the word back to their classrooms. At Dartmouth outdoors-minded professors and administrators would influence students in every decade from the 1920s onward, from the Med School's Rolf Syvertsen '18 and astronomer Dick Goddard '20 to boxing and rugby coach Corey Ford to the economics department's Greg Hines. For many of them, the canoe was an extension of the campus, perfectly scaled for adventure, close observation and quiet reflection.

As a vehicle, the canoe was ancient but democratic: accessible to young men and women, rich and poor and middle class, experts and amateurs alike. In the right hands it became a tool for learning about the world, and about oneself. It fit both sides of the workhard, play-hard culture that defined the modern College.

STRONG SYMBOLS OFTEN ENDURE IN THE FACE OF reality, and such is the case with the canoe. Forget that canoes played little or no actual role in campus life until late into the 1800s. At the time of Emerson's Philosophers' Camp, Dartmouth was a small, provincial training ground for future ministers, with no national cachet or members of the Eastern "literati." (The term "Ivy League" was still nearly a century away, and that denoted an athletic conference first and foremost.) Forget that the Connecticut River became so polluted that the annual downriver trip was suspended between 1935 and 1956. During the spread of Dartmouth's reputation for skiing and outdoor programs, the Connecticut was called "the nation's most beautifully landscaped sewer," and many students went four years barely knowing the river even existed. The sewer pipe from Mary Hitchcock Hospital, in fact, emptied into the river just above the Ledyard clubhouse. It would take the Clean Water Act of 1965 and years of work before students again made the river a regular part of their Dartmouth experience. Forget that Jay Evans '49 brought kayak racing into the Ledyard Club in the early 1960s and almost instantly transformed a sleepy organization into a national kayaking powerhouse. The club today is still strongly oriented toward kayaking; it counts 42 kayaks in its inventory, just 20 canoes.

Still, symbols reflect larger realities, and the canoe is part of the place and history and ethos of Dartmouth as perhaps no other single thing is. The kayak may have slipped past the canoe in importance at Dartmouth, but it lacks the canoe s bloodlines. You can thrill to whitewater in a kayak, but you can't go duck hunting as easily, or gunwale-bob or fall in love on a lazy trip downriver.

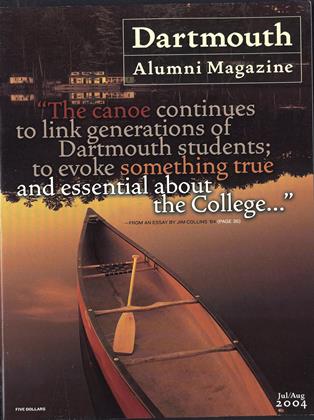

The canoe continues to link generations of Dartmouth students, to evoke something true and essential about the College. It reminds me of something Ted Williams once said when a reporter asked him what he thought of John Updike's New Yorker account of Williams' final game with the Boston Red Sox. Williams said, simply, "It has the mystique."

Other resonant symbols have disappeared or diminished over time. The Old Pine was damaged by lightning in 1877 and finished off bywind in 1892. The football flame flickered brightly only briefly, in the 19205. Snowshoeing has declined in popularity in recent decades; traditional beavertail snowshoes are usually found these days hanging on cabin walls. The Indian symbol was officially de-recognized in 1972. The ski jump came down in 1993. AnimalHouse, now more than a quarter-century old, loses currency with each passing year. Fraternities are falling from public fashion, as has Eleazar's barrel of rum. Varsity sweaters? Freshman beanies? The Senior Fence? The Macintosh computer? Other symbols—Dartmouth Hall, Baker Library—wonderfully represent the place, but not the character or spirit of the students who learn here. Even venerable old Baker has become an annex.

There are forces at the College that would de-emphasize Dartmouths setting and its outdoor traditions. Dartmouth has become a far more diverse and complex place than it was in the days of Ross McKenney. As Associate Dean of the College Dan Nelson '75 says, "That strong outdoor image used to be one of five or six kinds of psychic identities you could have at Dartmouth. Now it's probably one of 20 or 30 or 50."

But I think about the canoe, and what it can teach about risk and discovery, and what liberal education means in the broadest sense. God, I think of the fun I've had. I hope the canoe will endure as a symbol of Dartmouth, not just for what it is but for what it says about the character of Dartmouth students. I, too, am for the spirit that makes young men and women do the things they do. For the glory that they know.

Dartmouth claims the oldest and largest collegiate in the country, one that h&sr displayed a certain spirit from the very beginning.

JIM COLLINS, former interim editor of DAM, writes from Orange,New Hampshire, where he lives with his wife, two children and three canoes.His book about the Cape Cod Baseball League, The Last Best League (De Capo Press), was published this spring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureShoot to Thrill

July | August 2004 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

July | August 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

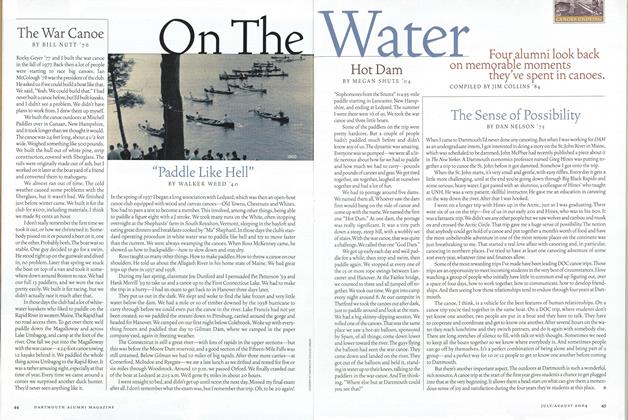

FeatureOn The Water

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionTrade, Jobs and Politics

July | August 2004 By Douglas A. Irwin -

Sports

SportsYouth at Risk

July | August 2004 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionMoney Matters

July | August 2004 By Andrew Mulligan ’05

JIM COLLINS ’84

-

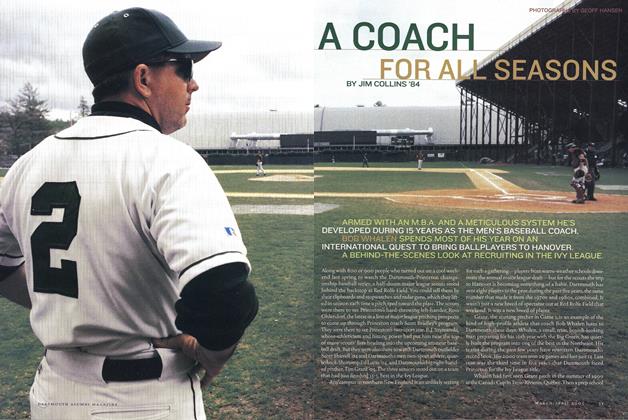

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

Mar/Apr 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

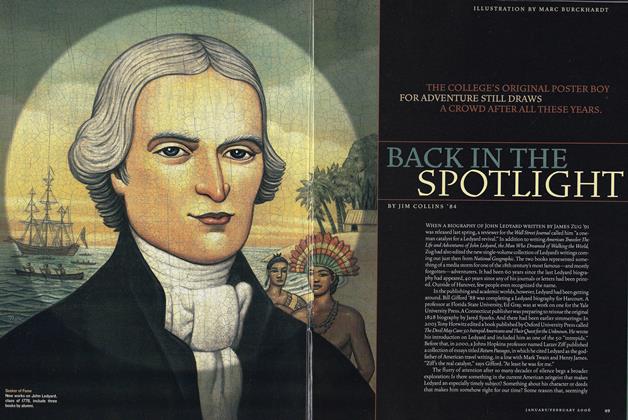

Feature

FeatureBack in the Spotlight

Jan/Feb 2006 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEFishing With George

May/June 2010 By Jim Collins ’84 -

Feature

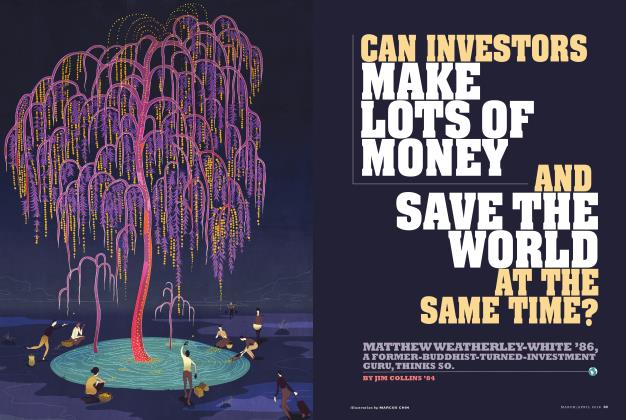

FeatureCan Investors Make Lots of Money and Save the World at the Same Time?

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

COVER STORY

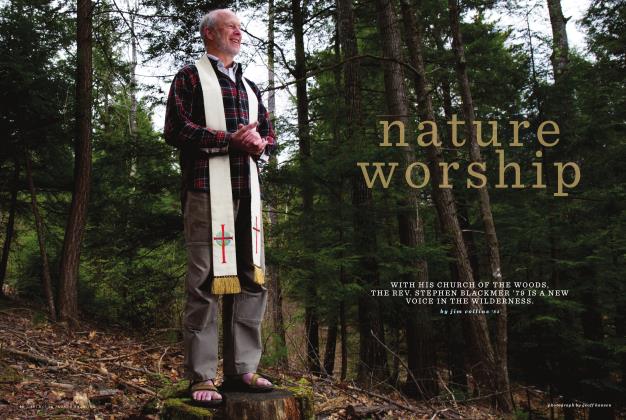

COVER STORYNature Worship

MAY | JUNE 2019 By jim collins ’84 -

Features

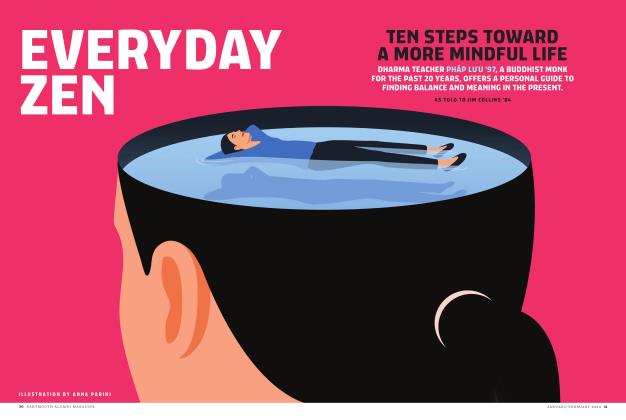

FeaturesEveryday Zen

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS ’84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

JULY 1973 -

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

APRIL 1991 -

Feature

FeatureCAT NORRIS

Sept/Oct 2010 -

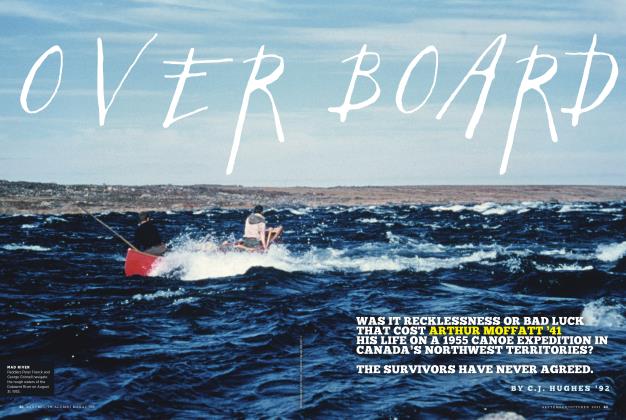

Features

FeaturesOverboard

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureONE HUNDRED MASTER DRAWINGS

October 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureReport of Twenty-Sixth Alumni Fund

April 1941 By SUMNER B. EMERSON '17