Trade, Jobs and Politics

Campaign rhetoric fails to acknowledge that the United States gains more jobs from outsourcing than it loses.

Jul/Aug 2004 Douglas A. IrwinCampaign rhetoric fails to acknowledge that the United States gains more jobs from outsourcing than it loses.

Jul/Aug 2004 Douglas A. IrwinCampaign rhetoric fails to acknowledge that the United States gains more jobs from outsourcing than it loses. BY

EVERY FOUR YEARS THE DARTMOUTH community is treated to a host of presidential candidates—and their media entourage—traipsing through Hanover. More often than not, the issue of jobs and trade is a part of the debate. Often candidates blame foreign countries for stealing our jobs and the incumbent president for doing nothing about it.

Many memorable campaign lines have come from this issue. In the early 1980s former Democratic Vice President Walter Mondale complained about our trade with Japan: "We've been running up the white flag when we should be running up the American flag. What do we want our kids to do? Sweep up around Japanese computers?"

In the early 1990s independent candidate Ross Perot predicted that we would all hear a "giant sucking sound" of jobs going to Mexico as a result of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In that same year Republican Pat Buchanan urged New Hampshire voters to raise their pitchforks and stop America from selling out its sovereignty and devastating its industrial base by keeping markets open to foreign competition. And for more presidential cycles than most people care to recall, Richard Gephardt (D-Mo.) has never missed a chance to say he is for "fair trade," including aggressive measures to combat foreign unfair trade practices and reduce the trade deficit.

Worries about international trade are inextricably bound up with concerns about domestic employment. When the unemployment rate is above average, foreign competition is blamed for job loss. When the unemployment rate is below average, foreign competition is blamed for pushing Americans into bad jobs with low wages.

It is true that there is an incredible amount of job loss in the United States. From 1993 to 2002, for example, the United States eliminated 310 million jobs. That's right: 310 million. Most involuntary job separations impose hardships on workers and are therefore a cause for concern.

But over the same period, the U.S. economy also created 328 million new jobs—for a net gain of 17.8 million jobs. Net job creation has been a feature of the U.S. economy for centuries. For this reason, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan recently remarked, "Over the long sweep of American generations and waves of economic change, we simply have not experienced a net drain of jobs to advancing technology or to other nations."

Trade is a small part of the problem, even in manufacturing. It is true that the number of manufacturing workers fell 12 percent between 1993 and 2003, but manufacturing output rose more than 40 percent during the same period. Just as in agriculture many decades ago, capital and technology have enabled productivity in manufacturing to soar: Many more goods are being produced, but fewer workers are required to produce them. (This is not just a U.S. phenomenon; many other advanced countries are losing manufacturing jobs at similar rates.)

And it is not the case that only "bad" jobs—flipping hamburgers at McDonalds (a 1980s story) or stocking shelves at Wal-Mart (a more contemporary version) have taken the place of good jobs. In fact, many of the manufacturing jobs that have been destroyed, such as those in the textile and apparel industry, were actually low-paying jobs. While jobs created in some service sectors (retail trade) are relatively low paying, many in other parts of the service sectorhealth services, finance and insurance, and wholesale trade—offer above-average compensation.

But in this past election season, a new twist on these old fears has arisen; the fear of lost jobs due to foreign competition has now spread to the white-collar service sector. No longer is it just farmers and manufacturers whose jobs are directly affected by the international economy. Firms are now "outsourcing" call centers, data processing and software programming—even work done by highly paid medical technicians such as radiologists—to English-speaking India and other countries. Senator John Edwards (D-N.C.) has attacked outsourcing, and Democrat presidential nominee John Kerry has criticized "Benedict Arnold CEOs" for having shifted jobs overseas. The concern about outsourcing is potent and demands attention, particularly since virtually every Dartmouth graduate now is going to be employed in the service sector, not on a farm or in a factory. Even if a fraction of the billion people in India have the requisite skills to perform service tasks, that is still a huge number. The potential for a giant "service-sector sucking sound" is readily apparent, and the issue has generated Business Week cover stories and is featured on Lou Dobbs' CNN "Exporting America" segment.

Restructuring is indeed rampant in the service sector, but—as is the case in manufacturing—this has more to do with changes in information technology than international trade. As Brink Lindsey of the Cato Institute has pointed out, "Bank tellers have been replaced by automatic teller machines; receptionists and operators have been replaced by voice mail and automated call menus; back-office record keeping and other clerical jobs have been replaced by computers; layers of middle management have been replaced by better internal communications systems. In all of these cases, jobs are not simply being transferred overseas; they are being consigned to oblivion by automation and the resulting reorganization of work processes."

Doesn't outsourcing promise to be an altogether new and different phenomenon? It remains to be seen just what fraction of service sector jobs are ripe for outsourcing, although even the largest estimates project just a small percentage of the white-collar workforce. It should be remembered that international trade—in services, as in goods—is not a one-way flow but a two-way street. In fact, more work actually gets outsourced to the United States than is outsourced to other countries. In 2003 the value of U.S. exports of legal work, computer programming, engineering, management consulting and other private services was $131 billion. U.S. imports of such services, including call centers and data entry in developing countries, among other things, was $77 billion. At a time when the United States is running a large merchandise trade deficit, the United States actually has a fairly substantial trade surplus in services.

This is true even in the narrower category of "computer and database processing service," in which the United States exported more than $5 billion and imported just more than $1 billion in 2002. For example, in late March of this year IBM won a 10-year, $750 million outsourcing contract from an Indian company. Bharti Tele-Ventures, India's largest private telecommunications corporation, will transfer some jobs from Asia to the United States and France. IBM will service Bharti's hardware and software requirements and take over its customer billing and relations operations.

Thus, while job loss related to outsourcing will undoubtedly create difficulties for some workers that should be addressed, not all service jobs can or will be outsourced—and outsourcing will create more opportunities for other U.S. workers.

The perception in the United States that outsourcing is a one-way street stems from our awareness of what we import from other countries. Americans are conditioned to think that just because wages are lower in other countries, work will automatically shift to those locations. But the world doesn't work that way. We sometimes forget that the United States sells a great deal to foreign countries

tries as well. We are often unaware that, while we focus on our weaknesses, the rest of the world sees things very differently. People in Mexico, China and India see our strengths and wonder how their local producers can ever compete against large, wealthy and technologically sophisticated American companies. One of the reasons India has been so slow to open its economy in past decades is because of its fear of foreign domination. As it now begins to do so, the United States is positioned to take advantage of many opportunities that the Indian market has to offer.

Indeed, international trade tends to bring out anxieties and insecurities in every country. With each passing decade, old fears about trade recede and new ones take their place. If the United States can restore the low unemployment rates and vigorous job creation seen during the 19905, the outsourcing debate could become a distant memory, much like the fears widely expressed in the 1980s that Japan would dominate America.

Americans are conditioned to think that just because wages are lower in other countries, work will automatically shift.

DOUGLAS A. IRWIN, professor of economics, is author of Free Trade Under Fire and Against the Tide: An Intellectual History of Free Trade (Princeton University Press).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

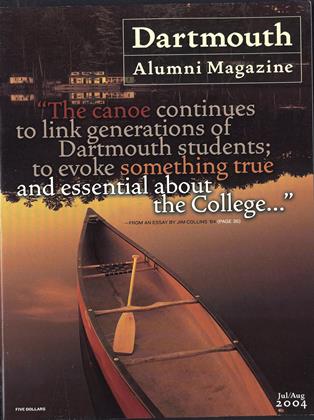

Cover Story

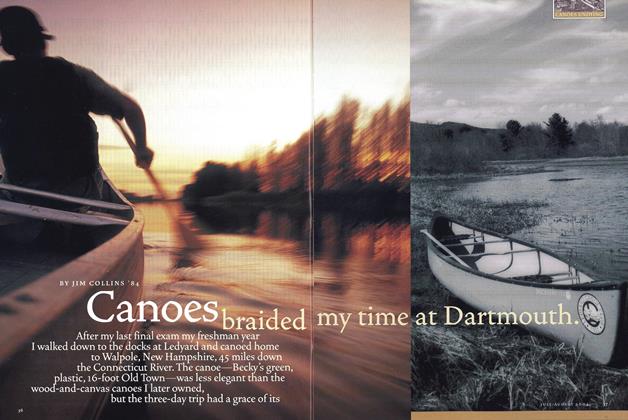

Cover StoryCanoes Undying

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

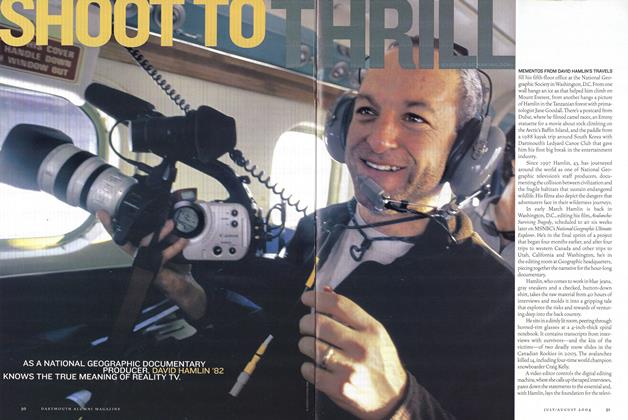

FeatureShoot to Thrill

July | August 2004 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

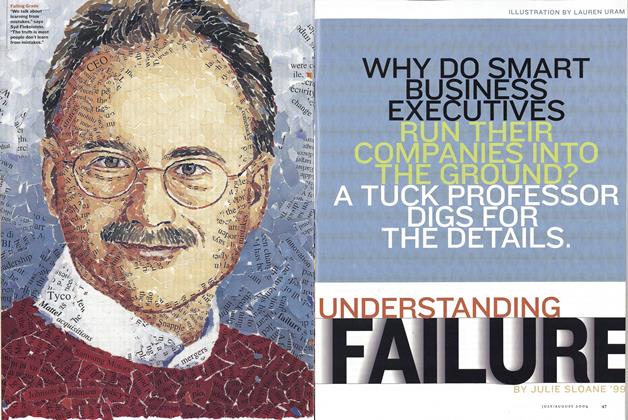

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

July | August 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Sports

SportsYouth at Risk

July | August 2004 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionMoney Matters

July | August 2004 By Andrew Mulligan ’05

Faculty Opinion

-

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

Mar/Apr 2004 By David C. Kang -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONCrossroads of the East

May/June 2008 By DAVID KANG -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Next Frontier

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jay C. Buckey Jr. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONShiny Bubble

May/June 2005 By JOHN H. VOGEL JR. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMyths of Innovation

Mar/Apr 2006 By Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionCan You Believe It?

May/June 2004 By Walter Sinnott-Armstrong