Youth at Risk

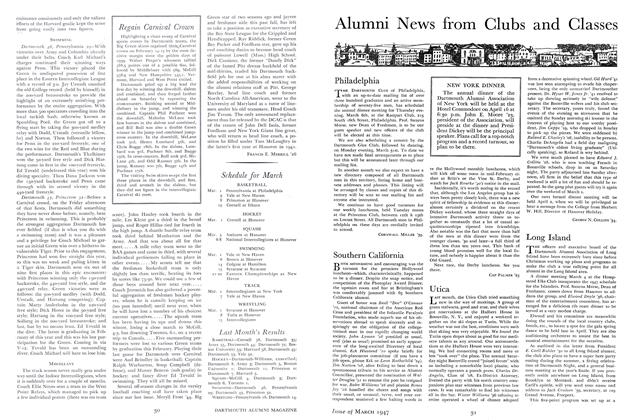

Sports pediatrician Sally Harris ’80 is alarmed that kids are being groomed for the college ranks at too early an age.

Jul/Aug 2004 Irene M. WielawskiSports pediatrician Sally Harris ’80 is alarmed that kids are being groomed for the college ranks at too early an age.

Jul/Aug 2004 Irene M. WielawskiSports pediatrician Sally Harris 'BO is alarmed that kids are being groomed for the college ranks at too early an age. BY

SALLY HARRIS WAS ALREADY A CONFODEMT athlete when she arrived at Dartmouth in the fall of 1976. Her parents were not the sort to raise couch potatoes. Avid golfers, tennis players and skiers, they nudged their three daughters toward the many outdoor activities of life in the San Francisco Bay Area. "Sports were part of the family routine," recalls Harris, a state-ranked tennis player who biked, hiked, swam, skied and played team sports for the sheer fun of it. She looked forward to playing tennis for Dartmouth, and, once there, managed to land berths on the women's basketball and crew teams, too.

That was then. Todays high school and college athletes would be hardpressed to duplicate her diverse experience, says Harris, now a Palo Alto, California, pediatrician specializing in sports medicine. This is the age of super sports specialization, in which children as young as 10 are pressured to hone skills in just one sport in order to have a shot at high school stardom and college scholarships. The trend has produced some remarkable achievers, but it has also resulted in a surge in so-called "overuse injuries" such as stress fractures, tendinitis and other wear-and-tear conditions virtually unheard of in youth sports a generation ago.

Overuse injuries today account for nearly half the sports injuries at the middle and high school level, an astonishing statistical spike that experts attribute to excessive wear and tear on immature bodies. Unlike acute injuries, such as broken bones and cuts, overuse injuries may take longer to heal because of micro-trauma to still-growing bones and tendons. Repeated stress injuries—say to a young pitcher's throwing arm or a soccer player's knee—can result in permanent joint damage. There also can be emotional and psychological consequences of too much, too young. Researchers have documented cases of sports burnout in children still in middle school.

Harris has been at the forefront of efforts by the American Academy of Pediatrics to alert parents to the dangers of pushing youngsters too hard while at the same time encouraging sports and physical activity as important for lifelong health. She is a former chair of the academy's section on sports medicine and has served on the California Governors Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. She lectures on sports medicine to doctors in training at Stanford University and has served as team physician for the U.S. women's basketball team and for high schools and colleges around Palo Alto. Harris also has participated in the Olympic Team Physician Program. In 2003 she was honored by the American Academy of Pediatrics for outstanding achievement in the field of pediatric and adolescent sports medicine.

As someone who thrived on youth sports and competition, Harris can appreciate the irony in her current role as a cautionary voice to parents and children swayed by overeager coaches and college recruiters. She still plays tennis, kayaks, runs, rows and swims whenever she can steal time from work. Her sons, Lucas, 4, and Scott, 6, often join her. Indeed, it is Harris' lifelong enjoyment of sports that fuels her commitment to prevent debilitating injury in the next generation.

"Part of what you are trying to do in youth is establish activity as a healthy behavior," says Harris, who in addition to her medical degree from Duke holds a masters degree in public health from the University of North Carolina. "The activities should mostly come from the child's interest, not be forced on them. Some kids thrive on weight training, some on martial arts. For girls, a lot of dance- and musicbased things are extremely popular. It doesn't always have to be team sports."

The trend among young athletes to specialize began a decade ago, experts say, fueled by burgeoning participation in organized sports programs and good old American entrepreneurship. Three quarters of U.S. households report at least one school-age child in organized sports, and an estimated 35 million children—more than half of the population aged 6 to 21 participate overall, according to the national SAFE KIDS Campaign. While the majority of these programs emphasize age-appropriate drills and sportsmanship, even the youngest T-baller knows the point is to win.

Enter the entrepreneurs: professional coaches, personal trainers, equipment hawkers, even motivational counselors eager to turn Juniors ambitions into cash. There's also a whole new sports camp industry. No summer idylls offered here. At some, children drill and compete all day long. Many of the camps have morphed into year-round businesses, offering training regimens after school, on weekends and during school vacation weeks. Some focus on a single sport and may promote themselves as a way to tune-up a child for team tryouts. A few such as pitchers' camps—concentrate on a single activity within a sport.

The pressure to maximize athletic ability reaches even into the elementary grades. Harris notes cases of "red-shirting" in kindergarten, when children are kept back by parents to give them a physical edge over classmates as they progress through school. Only a few years beyond kindergarten, youngsters can find themselves on a treadmill of school, league and travel team obligations that leaves little time for other interests, never mind family life.

Even if a child is eager to participate, some of the training programs simply can't deliver as advertised. A child's growth and physical development are highly variable; what helps one 12-yearold may do nothing for another. Adult conditioning regimens have virtually no benefit for children who have not reached puberty, says Harris. If a program director or personal trainer promises otherwise, they need to retake Physiology 101. "The worst example of this is swimming," says Harris. "You have these young kids swimming for hours and hours and hours, and they gain very little in terms of endurance and cardiovascular conditioning. The incremental gain between a half-hour and three hours is minute. And, obviously, there is a lot of downside from injuries and stress and burnout."

Some children are genuinely pas- sionate about a sport and derive not only pleasure but also confidence, leadership skills and other benefits. Still, says Harris, the adults around these youngsters have a responsibility to ensure they don't overwork their bodies—and that they do their homework.

This last point has been echoed in public service announcements by professional athletes emphasizing the importance of schoolwork for careers off the playing fields. A series of these ran during the NCAA Final pour basketball tournament last spring. Harris says there's a subtler message in these announcements, having to do with the way athletic ability plays out over the course of childhood. A terrific young basketball player with dreams of making it to the Final Four could ultimately end up benched for size—a hereditary reality that skill only rarely surmounts. Harris, who is 5-foot-10, notes that she'd probably get very little playing time at Dartmouth today.

"A lot of what parents see as athletic ability in their children at an early age may not bear out as they go through puberty," says Harris. Moreover, there are times when even the best young athletes need to pull back, typically after a growth spurt that can skew balance and coordination. A tennis player whose arms are suddenly two inches longer needs time to recover spatial orientation to the ball.

Harris' message is part of an overall campaign by the American Academy of Pediatrics to alert parents to both the benefits of sports and the dangers of pushing children to performance extremes. The academy's Web site (www.aap.org/family/ sportsshort.htm) has numerous tips on sports safety, ranging from advice on protective equipment to how much water children should drink during vigorous activity in order to avoid dehydration or heat stroke. Harris has similar postings on the Web site of her medical practice at the Palo Alto Medical Clinic (www.pamf.org/ sports/harriss).

www.aap.org/family/sportsshort.htm

www.pamf.org/sport/harriss

"A lot of the guidance and judgment has to come from parents," says Harris.

Voice of Reason Harris is an authorityon the dangers of pushing youngsterstoo hard on the playing fields.

IRENE M. WIELAWSKI is an awardwinning health-care journalist who contributesregularly to national publications and books.She lives in Pound Ridge, New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

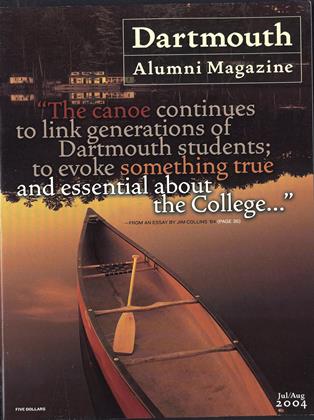

Cover StoryCanoes Undying

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

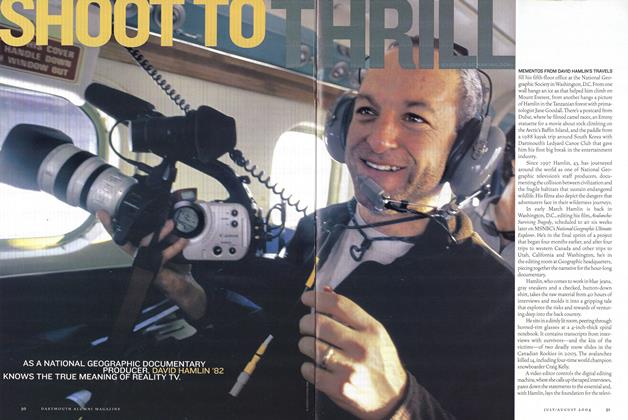

FeatureShoot to Thrill

July | August 2004 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

July | August 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureOn The Water

July | August 2004 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionTrade, Jobs and Politics

July | August 2004 By Douglas A. Irwin -

Student Opinion

Student OpinionMoney Matters

July | August 2004 By Andrew Mulligan ’05

Irene M. Wielawski

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMind Matters

Mar/Apr 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

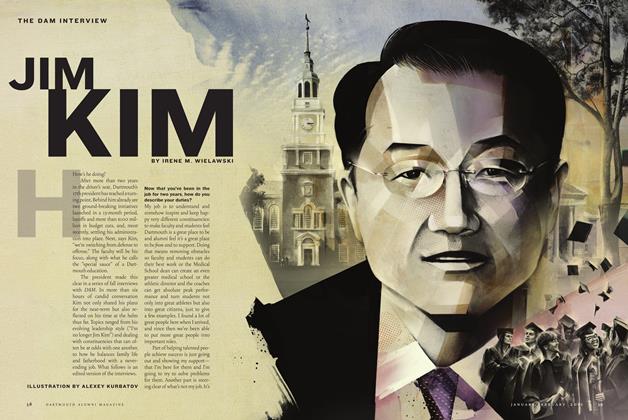

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWJim Kim

Jan/Feb 2012 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Cover Story

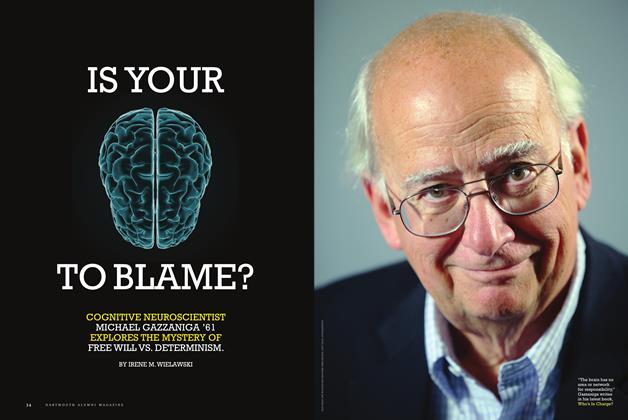

Cover StoryIs Your Brain to Blame?

Nov - Dec By Irene M. Wielawski -

ON THE JOB

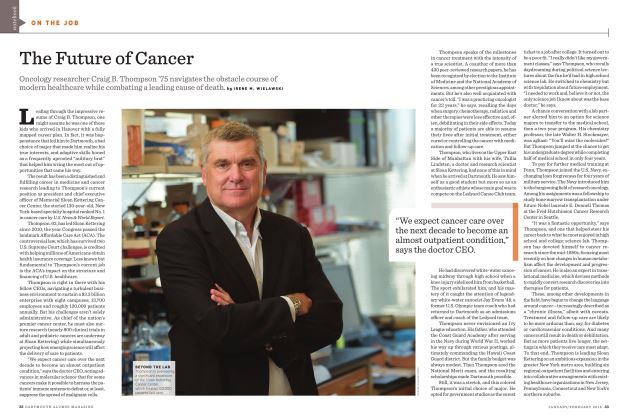

ON THE JOBThe Future of Cancer

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By Irene M. Wielawski -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYLifesaver

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Interview

Interview“It Has Been a Difficult Year”

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By Irene M. Wielawski