Framing the Letter

Why that infamous missive from the dean of admissions might be remembered as the letter that saved Dartmouth athletics.

Mar/Apr 2005 Brad Parks ’96Why that infamous missive from the dean of admissions might be remembered as the letter that saved Dartmouth athletics.

Mar/Apr 2005 Brad Parks ’96Why that infamous missive from the dean of admissions might be remembered as the letter that saved Dartmouth athletics.

FOR A COLLEGE THAT HAD JUST fired a loyal and likeable football coach and for an athletic program that had already taken enough lumps, the story that appeared in the December 10 edition of the Valley News was a fresh bruise laid on top of a growing welt. It revealed the existence of a 4-year-old letter, authored by Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid Karl M. Furstenberg, printed on College stationery and addressed to Alfred Bloom, president of Swarthmore College.

In the now-notorious letter, Furstenberg commended Bloom for dropping the school's football program. "Other institutions would do well to follow your lead,"Furstenberg wrote."I,for one, support this change." It went on to say that "...football programs represent a sacrifice to the academic quality and diversity of entering first-year classes." And that "....football, and the culture that surrounds it, is antithetical to the academic mission of colleges such as ours." And: "A close examination of intercollegiate athletics within the Ivy League would point to other sports in which the same phenomenon is apparent."

At a school where one quarter of the student body participates in intercollegiate athletics, those were fighting words. Furstenberg's hasty apology and explanation—that he was just trying to support a colleague in crisis through a private letter and that his remarks had no bearing on how he did his job—did little to pacify the outrage.

"I call it the perfect storm," says Don Mahler, the longtime Valley News sports editor who broke the story. "Because first football went 1-9, then John Lyons got fired, then the letter."

Outside Hanover, word quickly traveled along the well-worn electric pathways that connect alumni. Four members of the class of 1993—John Conley, Alex Gayer, Greg Hoffmeister and Joe Tosone—started a petition calling for Furstenbergs ouster. They got 432 signatures. Bill Wellstead '63, a former football player, started a blog on Dartmouth athletics (www.dartmouthathletics.blogspot.com). When printed out, the spleen it spawned in just one month fills 208 pages.

"What you're seeing on the blog is just a lot of pent-up frustration being expressed," Wellstead says. "The Furstenberg letter really crystallized a lot of what is wrong with Dartmouth football and Dartmouth sports today."

And yet, as bizarre as it may seem, the Furstenberg letter might also be the best thing to happen to Dartmouth football since Jay Fiedler '94. So far, it has led to President Jim Wrights strongest statements ever in support of athletics; to the hiring of former Stanford coach Buddy Teevens '79; and to a detente in the long war between athletics and admissions. It's entirely possible Furstenberg's stinging missive will end up in the Unintended Consequences Hall of Fame—as The Letter That Saved Dartmouth Sports.

MAKE NO MISTAKE, DARTMOUTH sports need saving. In 1995, as editor of The Sports Weekly, a now-defunct student paper I started in my dorm room, I did a numerical survey comparing Dartmouth's athletic program to the rest of the Ivy League. At that time Dartmouth placed second overall. Ten years later Wellstead duplicated my procedure and found Dartmouth tied for sixth place. We finished last or second-to-last in 10 of 30 sports. Only Columbia—crammed in the middle of New York City—did worse.

Before Furstenberg came along, the common culprit cited for the decline was Dartmouth's rising Academic Index (AI), a formula that factors SAT scores and class rank. Under Ivy League rules, an athletes Al must be within a certain range of the general student population. Around 1996 or 1997, Dartmouth's skyrocketing admissions profile pushed its Al into the same realm as Harvard, Yale and Princeton. And Dartmouth found it had neither the facilities nor the financial aid resources to consistently compete with those schools for recruits.

Then came the Furstenberg letter, and fans of Dartmouth sports had a new villain: the man who is the final word on all admissions and financial aid decisions.

Dig deeper, and there's more. Of Dartmouth's new $1.3 billion capital campaign, only $22 million is dedicated to athletics—half of which is going to the intramural program. That means, of every dollar generated during the capital campaign, less than one-tenth of a penny will go to intercollegiate sports (even though a quarter of the student body participates in them). Who chaired the long-range planning committee that helped determine how those capital campaign dollars would be spent? Karl Furstenberg.

Or look at the struggles of some teams other than football. Supporters of men's basketball, which hasn't won a league title since 1959, tell the story of prospect Craig Austin. He had an Al above 190, well over the 169 minimum. He committed to attend Dartmouth but wasn't allowed in. He went to Columbia instead and ended up the Ivy League Player of the Year in 2001. Why didn't he get in? A source in the athletic department says it was because Furstenberg didn't like the kid's essays.

"Other schools have committees to discuss their athletic admissions," says Jim Barton '89, Dartmouth's all-time leading scorer in mens basketball. "At Dartmouth we have a committee of one. And his commitment to athletics is a joke."

IT WAS AGAIN ST THIS BACKDROP OF discontent that athletic director Josie Harper began searching for Lyons' replacement. The Letter had supercharged the always-electric issue of finding a football coach, and with millions of dollars of alumni support potentially at stake, Dartmouth could ill-afford to hire some noname Division III coach with stars in his eyes. It had to make a splash.

Enter Teevens. To misty eyed alums yearning for a return to glory, it seemed like serendipity when Teevens and Lyons were fired within a day of each other in November. As a player on the 1978 team, Teevens quarterbacked an overachieving group to an unlikely Ivy League championship. As a coach from 1986 to 1991, he resurrected Dartmouth football from the morass of the mid-1980s, won championships his last two seasons and recruited the players who won another for Lyons in 1992.

Still, most insiders believed there was no way a Division I-A coach such as Teevens—who is owed $8OO,OOO by Stanford over the next two years whether he coaches or not—would slide back into coaching Division I-AA. Teevens says he viewed the Dartmouth job as merely "a curiosity" when first contacted about it. He had other offers. The smart money had Teevens heading to South Carolina to reunite with Steve Spurrier, his onetime boss at Florida.

But that, of course, was before The Letter changed how athletics are being viewed in Hanover. To begin with, it has spurred a new openness in the admissions process. President Wright has made it clear that Furstenberg will keep his job. But his decisions will be subjected to far greater scrutiny.

More importantly, there seems to be a new awareness of athletics in the corner office at Parkhurst. "The reaction to the letter reminded President Wright how passionate people around here are about athletics," Harper says. "It's had a lot to do with his recommitment."

Teevens has certainly been convinced. In a series of on-campus meetings before Teevens accepted the job, Wright repeatedly said he wanted to win and was willing to do what it took. "If that presentation isn't there, I'm not coming back to Dartmouth, plain and simple," Teevens says. "But the support is absolutely there."

Translation: When it comes to admissions, Buddy Teevens now has more juice than Tropicana.

His press conference during the first week in January was reminiscent of a high school pep rally. Held at the Hanover Inn's Hayward Lounge, there was barely enough room to contain all the attendees and nowhere near enough room to contain all the jubilation. Teevens was forthright about the work that needs to be done, but there was a palpable sense that Dartmouth football was back in business.

Chances are, if Teevens can guide the Big Green to another Ivy title, no one is going to want to see Furstenberg on the podium to help accept the trophy. Yet maybe they'll let him park it in his office for a while.

Right next to a framed copy of the letter that helped make it happen.

There seems to be a newawareness of athletics inthe corner office at Parkhurst.

BRAD PARKS is a staff writer forThe Newark Star-Ledger. His beloved paper, The Sports Weekly, folded in 2001. He hopes it can makea comeback alongside Dartmouth football.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

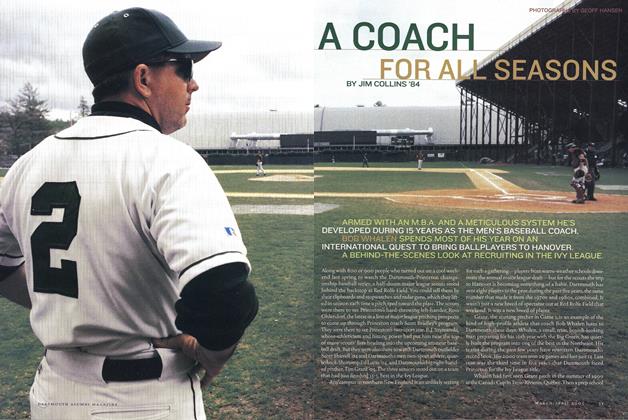

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

March | April 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

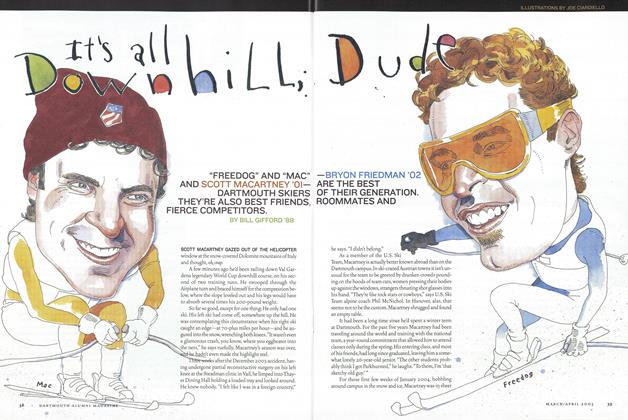

FeatureIt’s All Downhill, Dude

March | April 2005 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

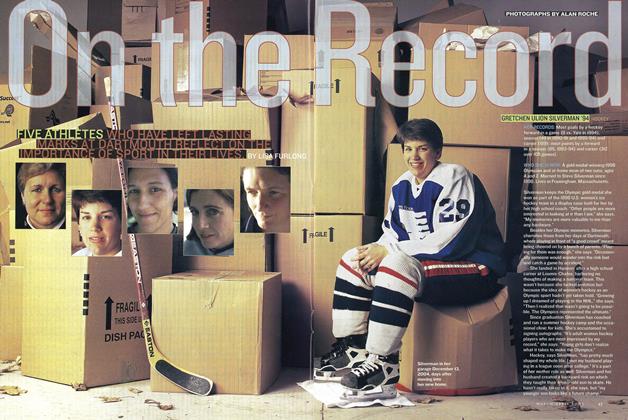

FeatureOn the Record

March | April 2005 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2005 By Gray Mercer '83 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

March | April 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66

Brad Parks ’96

-

Cover Story

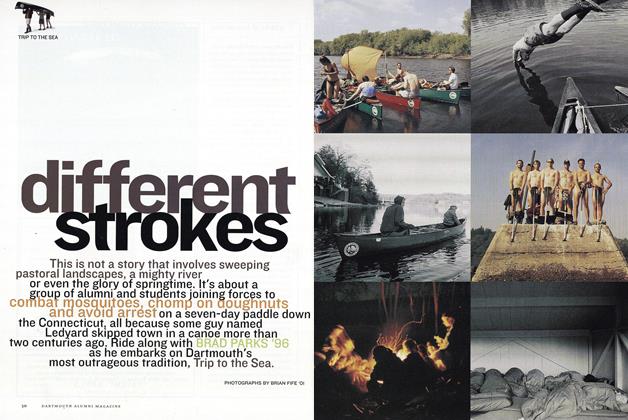

Cover StoryDifferent Strokes

May/June 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Interview

Interview“We’ve Got To Go For It”

July/Aug 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

SPORTS

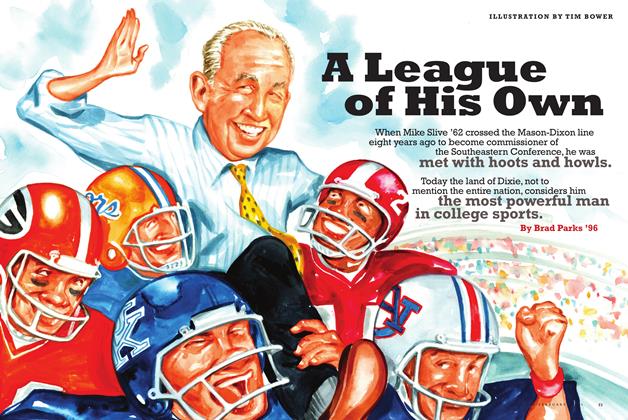

SPORTSIn a League of His Own

May/June 2009 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ones To Watch

Jan/Feb 2010 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Feature

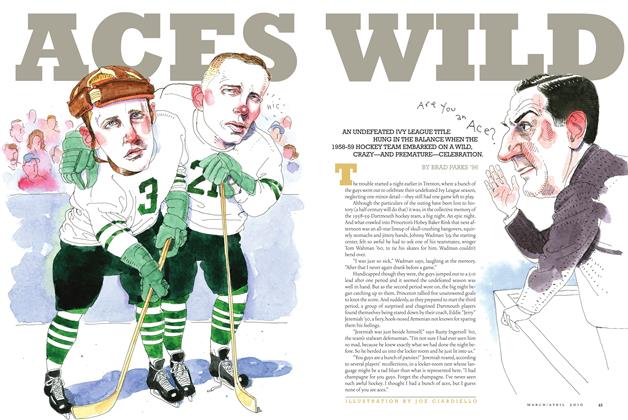

FeatureAces Wild

Mar/Apr 2010 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureA League of His Own

Jan/Feb 2011 By Brad Parks ’96