Eggheads vs. Meatheads?

The campus debate over the place of athletes—and athletics—overlooks more important questions.

Nov/Dec 2005 DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAMThe campus debate over the place of athletes—and athletics—overlooks more important questions.

Nov/Dec 2005 DAVID KANG AND ALLAN STAMThe campus debate over the place of athletes—and athletics overlooks more important questions. By David Kang And Allan Stam

TO ITS GREAT CREDIT, THE DARTMOUTH community is engaged in a debate about the place of intercollegiate athletics in undergraduates' education. Unfortunately, the conversation has taken an often-divisive path. In editorials and opeds alums express sincere outrage, faculty members wring their hands and the administration issues bland platitudes. In every instance, by focusing on the relative merits of athletes versus those of other students, the debate has missed the most important issue: how best to enhance the process of bringing the top candidates of many groups, athletes as well as those devoted to other interests, to Dartmouth.

The pursuit of athletic excellence is not antithetical to intellectualism and community participation. Students with interests far removed from sport face demands for their time every bit as pressing as those imposed by the Colleges varsity coaches. Indeed, the diversity of our students' passions is what makes teaching at Dartmouth a joy.

As Division I letter-winners turned tenured college professors, we have a deep appreciation of the benefits athletic competition provides. We also believe that any discussion of the role of athletics should focus first on the purpose of a Dartmouth education, while accepting the institutions central problem: Dartmouth walks a fine line between being either the largest of the liberal arts colleges or the smallest of Americas elite research universities.

As we consider how to remain competitive with larger, often wealthier schools, we must keep asking what skills and resources we should offer our students to equip them for the rapidly changing world they will soon encounter. We should focus on how successfully we are preparing students to thrive in their future lives.

While cooperation and group effort characterize American adult life, so does competition. The important point from a teaching perspective is that competition—whether athletic or professionalinvolves losing as well as winning, risk as well as reward. We must equip our students to deal with the rejection of their ideas and values as often as they find acclaim, comfort or unalloyed support.

Our shared sense from observing Dartmouth's athletes in our classrooms is that by balancing daily the competing demands posed by professors, coaches and friends they learn much about succeeding in life after college. Athletes at Dartmouth must motivate themselves to work harder than they previously thought possible toward goals they may not achieve. They also must learn to deal with complex group dynamics associated with the brutal reality that not everyone gets to participate when it counts most. Athletes often must make a tradeoff: marginally lower grades in exchange for the thrill of athletic competition. This prepares them well for future challenges.

In defining Dartmouth's purpose we should look to peer institutions as a basis of comparison. Most of Americas elite schools find themselves solidly in one of two camps of educational institutionsliberal arts colleges such as Williams and Amherst versus large research universities such as Stanford and Harvard.

Regardless of which group they belong to, most elite schools are not only secure in their ability to define acceptable community standards but also comfortable with their levels of academic and athletic competition. Dartmouth, frequently for the better, occasionally for the worse, finds itself perched between the two groups, which makes it difficult to frame any discussion about athletics.

The increasingly competitive nature of scholarly research as well as increased competition to recruit the best students means that Dartmouth can no longer simply position itself as a larger Amherst or a smaller Harvard. Those schools with which Dartmouth competes now recruit outstanding students and athletes as well as faculty from an international pool.

That these students typically demonstrate excellence in one or two pursuits rather than skill in numerous areas only heightens the tensions between the constituencies in Hanover. Until recently the interests of scholars, intellectuals and athletes were more complementary, with faculty and students holding similar views of each other s—and the Colleges—roles. The changes that have occurred are not unique to Dartmouth. Today many faculty see their schools as intellectual clubhouses, settings in which to conduct scholarship and writing the outside market would not support. Many students in turn view college as a steppingstone to material success, a place where networking and GPAs are the most important measurements of progress. For their part, some athletes see college merely as a place to participate in their sport at the highest level. Today these groups often feel they are in a zero-sum competition for limited resources.

Our students tell us they do not want Dartmouth to become a "Big Williams." They enjoy knowing that they are at a Top 10 school academically—and they want Dartmouth to compete in the NCAA's Division I.

How do we retain what makes Dartmouth unique and so attractive to the best students in America, while remaining competitive on an expanding playing field for faculty and students alike? Once we attract the best, how do we prepare students for life after Dartmouth? Here are some practical suggestions.

First, the College should accelerate its current drive to construct better athletic facilities for both varsity and recreational athletes. The lack of lighted facilities for athletic practices is a real problem. Because darkness comes early by October in northern New England, many coaches are forced to start practices no later than 3 p.m. This eliminates a broad range of courses from athletes' consideration and reinforces the stereotype that they seek out only particular types of classes. If coaches could hold practices from 5 to 7 p.m. under artificial lighting, students who wanted to could take more of those upper-level classes commonly offered in the afternoon. In addition to varsity sports, Dartmouth and its competitors have made substantial investments in recreational sports facilities, which in turn generate increased interest and participation across the student body.

Second, the Dartmouth College Athletic Council should serve a more active and regular role facilitating communication among faculty, coaches and athletes. Faculty are often unaware of scheduling constraints that coaches face and coaches would be well served by having more frequent conversations with their faculty peers to better understand the faculty's concerns and priorities. Administrative stumbles such as the move to eliminate the swim team might be avoided in the future if existing institutional arrangements were put to better use.

Third, the College should deemphasize the annual class as a focal point for student identity. The desire held by many to graduate with "one's class" is the least important aspect of an undergraduate education. Dartmouth's culture stigmatizes those who do not graduate with "their class" in both subtle and explicit ways, such as calling them "super seniors" or excluding them from corporate recruiting. Why not allow Dartmouth students to step off the treadmill without any explanation at all? If students take time off to mature and think through their goals, they often return more productive and happier.

Finally, we hope, as do our students, the College retains its position within the NCAA's Division I. Unilateral change would signal an exit from the Ivy League, established to foster athletic competition at the highest level among a group of universities committed to excellence in academics and scholarship. The principles behind the founding of the Ivy League are as valid today as they were in 1954, when eight of Americas elite universities first agreed to adopt a set of common values. These include a commitment to needbased financial aid, common and high academic standards and the notion that recruited athletes should be representative of other students on campus. In these values lies the key to understanding the place of athletics on the Dartmouth campus.

Coaches would be well served by having more conversations with their faculty peers.

DAVID RANG is an associate professor of government. ALLAN STAM is the Daniel WebsterProfessor of Government.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureForged by Flame

November | December 2005 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

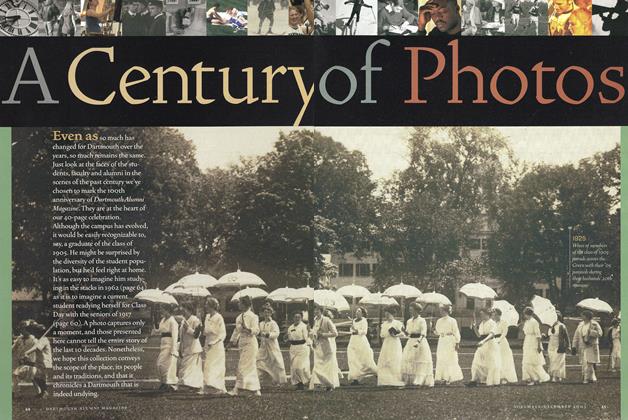

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Photos

November | December 2005 -

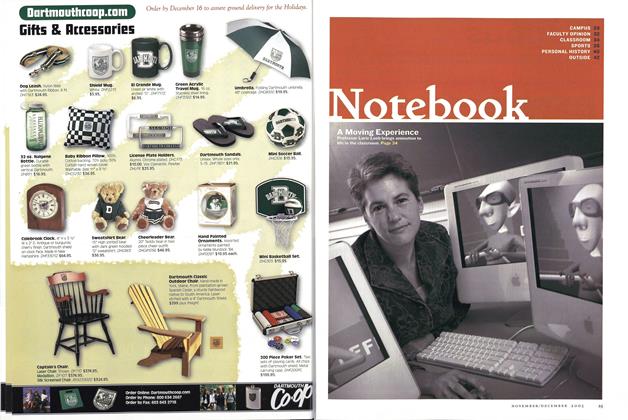

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2005 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2005 By Heather Brubaker '97, Heather Brubaker '97 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEDog Day Afternoons

November | December 2005 By LISA DENSMORE ’83 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPaying the Price

November | December 2005 By JEFF DUDYCHA ’93

FACULTY OPINION

-

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May/June 2003 By Jack Shepherd -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONShiny Bubble

May/June 2005 By JOHN H. VOGEL JR. -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONAcross the Divide

July/August 2006 By Lucas Swaine -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Cost of Winning

Mar/Apr 2003 By Professor Ray Hall -

FACULTY OPINION

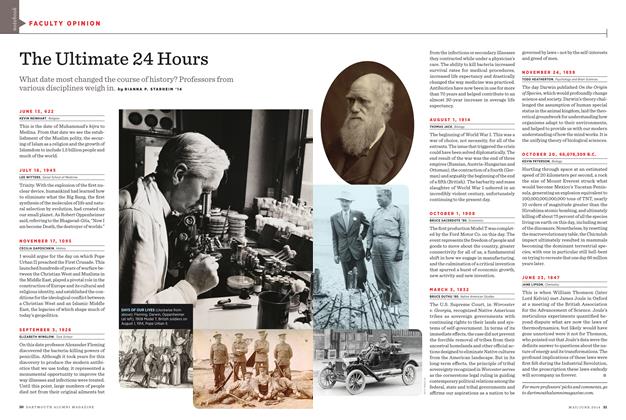

FACULTY OPINIONThe Ultimate 24 Hours

MAY | JUNE 2014 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionEyes Wide Shut

Sept/Oct 2003 By Sydney Finkelstein