Running Uphill

A former cross-country runner remembers with fond admiration his inspirational coach and mentor.

Nov/Dec 2005 RICHARD A. HOGARTY ’55A former cross-country runner remembers with fond admiration his inspirational coach and mentor.

Nov/Dec 2005 RICHARD A. HOGARTY ’55A former cross-country runner remembers with fond admiration his inspirational coach and mentor.

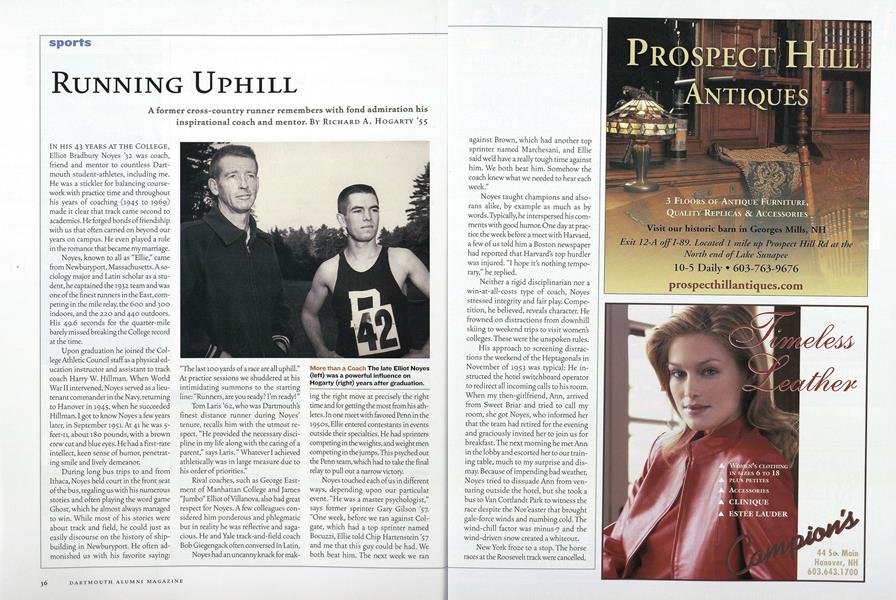

IN HIS 43 YEARS AT THE COLLEGE, Elliot Bradbury Noyes '32 was coach, friend and mentor to countless Dartmouth student-athletes, including me. He was a stickler for balancing coursework with practice time and throughout his years of coaching (1945 to 1969) made it clear that track came second to academics. He forged bonds of friendship with us that often carried on beyond our years on campus. He even played a role in the romance that became my marriage.

Noyes, known to all as "Ellie," came from Newburyport, Massachusetts. A sociology major and Latin scholar as a student, he captained the 1932 team and was one of the finest runners in the East, competing in the mile relay, the 600 and 300 indoors, and the 220 and 440 outdoors. His 49.6 seconds for the quarter-mile barely missed breaking the College record at the time.

Upon graduation he joined the College Athletic Council staff as a physical education instructor and assistant to track coach Harry W. Hillman. When World War II intervened, Noyes served as a lieutenant commander in the Navy, returning to Hanover in 1945, when he succeeded Hillman. I got to know Noyes a few years later, in September 1951. At 41 he was 5-feet-11, about 180 pounds, with a brown crew cut and blue eyes. He had a first-rate intellect, keen sense of humor, penetrating smile and lively demeanor.

"The last 100 yards of a race are all uphill." At practice sessions we shuddered at his intimidating summons to the starting line: "Runners, are you ready? I'm ready!" During long bus trips to and from Ithaca, Noyes held court in the front seat of the bus, regaling us with his numerous stories and often playing the word game Ghost, which he almost always managed to win. While most of his stories were about track and field, he could just as easily discourse on the history of shipbuilding in Newburyport. He often admonished us with his favorite saying:

Tom Laris '62, who was Dartmouth's finest distance runner during Noyes' tenure, recalls him with the utmost respect. "He provided the necessary discipline in my life along with the caring of a parent," says Laris. "Whatever I achieved athletically was in large measure due to his order of priorities."

Rival coaches, such as George Eastment of Manhattan College and James "Jumbo" Elliot of Villanova, also had great respect for Noyes. A few colleagues considered him ponderous and phlegmatic but in reality he was reflective and sagacious. He and Yale track-and-field coach Bob Giegengack often conversed in Latin.

Noyes had an uncanny knack for making the right move at precisely the right time and for getting the most from his athletes. In one meet with favored Penn in the 1950s, Ellie entered contestants in events outside their specialties. He had sprinters competing in the weights, and weight men competing in the jumps.This psyched out the Penn team, which had to take the final relay to pull out a narrow victory.

Noyes touched each of us in different ways, depending upon our particular event. "He was a master psychologist," says former sprinter Gary Gilson '57. "One week, before we ran against Colgate, which had a top sprinter named Bocuzzi, Ellie told Chip Hartenstein '57 and me that this guy could be had. We both beat him. The next week we ran against Brown, which had another top sprinter named Marchesani, and Ellie said wed have a really tough time against him. We both beat him. Somehow the coach knew what we needed to hear each week."

Noyes taught champions and alsorans alike, by example as much as by words.Typically, he interspersed his comments with good humor. One day at practice the week before a meet with Harvard, a few of us told him a Boston newspaper had reported that Harvard's top hurdler was injured. "I hope it's nothing temporary" he replied.

Neither a rigid disciplinarian nor a win-at-all-costs type of coach, Noyes stressed integrity and fair play. Competition, he believed, reveals character. He frowned on distractions from downhill skiing to weekend trips to visit women's colleges. These were the unspoken rules.

His approach to screening distractions the weekend of the Heptagonals in November of 1953 was typical: He instructed the hotel switchboard operator to redirect all incoming calls to his room. When my then-girlfriend, Ann, arrived from Sweet Briar and tried to call my room, she got Noyes, who informed her that the team had retired for the evening and graciously invited her to join us for breakfast. The next morning he met Ann in the lobby and escorted her to our training table, much to my surprise and dismay. Because of impending bad weather, Noyes tried to dissuade Ann from venturing outside the hotel, but she took a bus to Van Cortlandt Park to witness the race despite the Nor easter that brought gale-force winds and numbing cold. The wind-chill factor was minus-7 and the wind-driven snow created a white out.

New York froze to a stop. The horse races at the Roosevelt track were cancelled, but we thinly clad mortals ran—in short pants. Byway of "protection" we rubbed our bare arms and legs with a mixture of oil of wintergreen and analgesic balm. With the bang of the starter's gun, we were off, and I soon found myself buried in the middle of the pack, preferring to let runners in front of me block the fierce winds. As we gradually thinned out, I emerged from the pack and trudged through the snow over the tortuous 5-mile course. It was for the most part an equestrian bridle path with plenty of steep hills but no horses in sight. Maneuvering on such slippery terrain was treacherous. Several runners took nasty spills on rocks hidden by the new-fallen snow.

Noyes appeared at various strategic locations along the route, exhorting us as he shouted out our individual times. Approaching a pivotal point in the race, I felt a sudden surge of adrenaline that carried me through to the end. Having run one of the best races of my career, I was the first Dartmouth runner to finish. One by one, teammates Walter Clarkson '54, Peter Jebsen '55, Philip Langtry '56, Paul Merriken '55 and Mark Starr '55 stumbled across the snow-blurred finish line. Unhappily, Dartmouth wound up in sixth place. The last hundred yards of the race were not only uphill, they were as slippery as the skating rink at Rockefeller Center.

After the race Ann and I managed to have dinner at the hotel. Early the next morning she caught a train back to Sweet Briar and I returned to Hanover, where on subsequent visits Ellie and his wife, Martha, became fond of Ann. We stayed in touch after graduation and saw them at reunions. They had a positive influence on our marriage, including child-raising.

Few people spend as much time with students as coaches do; fewer are true mentors. Ellie taught us the finer aspects of competitive foot racing, but he also helped us understand what was really important in life: character.

More than a Coach The late Elliot Noyes (left) was a powerful influence on Hogarty (right) years after graduation.

RICHARD A. HOGARTY, a two-time captainof the Dartmouth cross-country team, isemeritus professor of political science at the Universityof Massachusetts in Boston.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureForged by Flame

November | December 2005 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Century of Photos

November | December 2005 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

November | December 2005 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

November | December 2005 By Heather Brubaker '97, Heather Brubaker '97 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEDog Day Afternoons

November | December 2005 By LISA DENSMORE ’83 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPaying the Price

November | December 2005 By JEFF DUDYCHA ’93

Sports

-

Sports

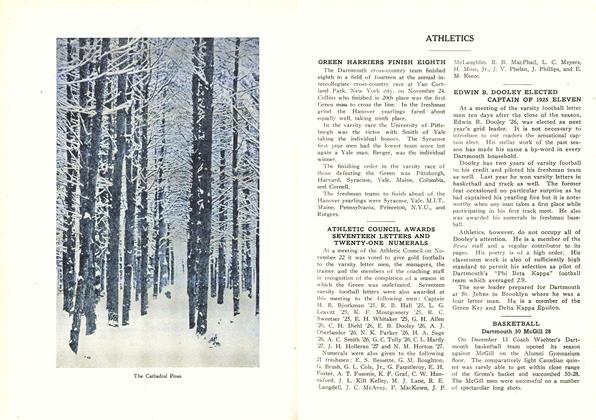

SportsEDWIN B. DOOLEY ELECTED CAPTAIN OF 1925 ELEVEN

January, 1925 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth 3—Yale 4

MARCH, 1928 -

Sports

SportsFootball Broadcasts

November 1949 -

Sports

SportsEverybody's Records

MARCH 1982 By Brad Hills '65 -

Sports

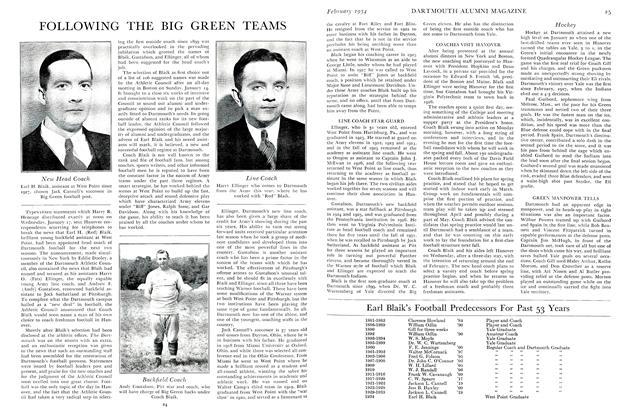

SportsLINE COACH STAR GUARD

February 1934 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Sports

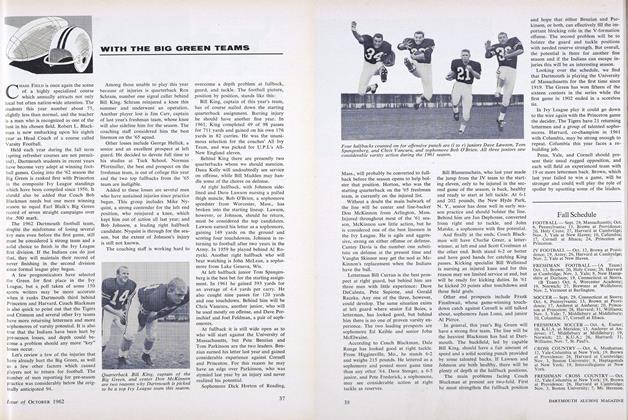

SportsWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

OCTOBER 1962 By Dave Orr ’57