More than a Game

Thanks to a College advising program, many students look to professors for help in balancing academics and athletics.

Mar/Apr 2005 Lauren Zeranski ’02Thanks to a College advising program, many students look to professors for help in balancing academics and athletics.

Mar/Apr 2005 Lauren Zeranski ’02Thanks to a College advising program, many students look to professors for help in balancing academics and athletics.

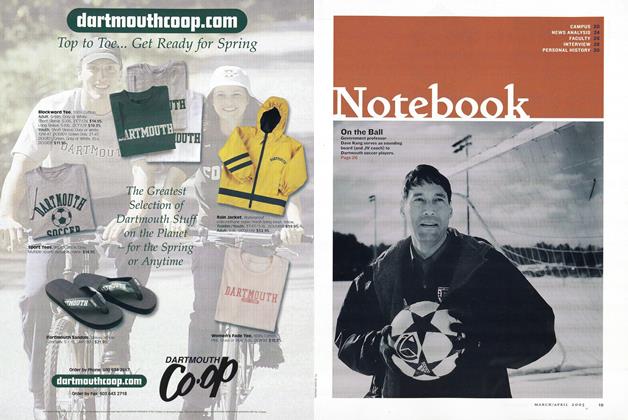

DAVE KANG IS A BUSY GUY. AN associate professor of government, adjunct associate professor at Tuck and expert on political economy and Asian international relations, he spends most afternoons enhancing another facet of Dartmouth life: athletics. Kang is the faculty advisor to the men's soccer team, and he tries to attend every practice and home game. A former college soccer player himself, he also is a volunteer coach of the men's JV team and assists both men's and women's teams in any way he can. By all accounts, he is a paragon for a young but increasingly vital college program.

Dartmouth's Faculty Athletic Advisor Program is administered through the Academic Skills Center (ASC), which matches professors with athletic teams in an effort to bridge the gap between sports and scholarship—fostering greater un- derstanding among coaches, athletes and faculty.TheColle ge's formal stance on un- dergraduate athletics, as heralded on the ASC's Web site, is that participants should be "students first, athletes second." Class attendance takes precedence over athletic participation, and missing practices due to academics cannot influence coaches. In reality, the College recruits not only top-notch brains but also high-level athletes eager to compete in Ivy League and NCAA Division I athletics. Combine this on- and off-the-field rigor with the complexities of the D-plan and the allure of the Colleges off-campus programs, and you could have trouble.

Carl Thum, director of the ASC, acts as the faculty advisor to the mens baseball team. Aware of the tremendous strain student athletes can feel, he enthusiastically supports the program. "Once students get to Dartmouth, reality hits," he says. "Most of the time they come from high schools that didn't prepare them for this tremendously challenging academic environment. Student-athletes do what everyone else must do, but then also deal with another major commitment every single term." Athletes often take less-demanding courses in season and plan far in advance for study abroad, if they can participate at all. Time management, a struggle for every college student, becomes paramount for athletes; with fewer hours for studying, they must employ more focus and discipline. Each trimester can be a tightrope walk for student-athletes, who wobble precariously between the demands of professors and coaches.

The now-formalized advisory program grew organically from a casual association between certain professors and sports teams. However, the need for greater support for student-athletes was first voiced by former basketball star Courtney Banghart '00 and one of her professors, Cathy Cramer, associate professor and undergraduate chair of the psychological and brain sciences department. Banghart wrote a class paper for Cramer relevant to her experience as a basketball player and confided to Cramer that she rarely told her professors she was an athlete. "I knew that some professors were not big fans of athletes, and I wanted to be seen as a student first," says Banghart, who is now assistant coach to the women's basketball team. "Professor Cramer seemed shocked and told me that I should be proud to be both—equall yall the time." A tennis and squash player, Cramer feels strongly that the faculty should encourage the development of athletic talent as they would any others. "I overheard faculty members talking from time to time about the juggling act student-athletes must accomplish, but I didn't think many understood the level of commitment involved," says Cramer. "I started encouraging my colleagues to go to sports events, and several came back surprised at how talented their students were. It gave them a new appreciation for the role of athletics in students' lives."

By reaching out through the program, Banghart and Cramer hoped to increase faculty awareness about the challenges of undergraduate athletics, and bring coaches, faculty and students together to discuss concerns. Aleading source of tension between professors and athletes is lack of planning, according to Cramer, who in addition to counseling students attends home games and lunches with coaches. "What drives professors crazy is the student who e-mails you before he gets on the bus going to an away game, the night before an exam, saying he can't take your test," she says. Encouraging students to communicate in advance about scheduling issues, and presenting professors with alternatives, is a fundamental message faculty athletic advisors now convey to their teams.

Like Cramer and Kang, most faculty advisors are athletes themselves or feel connections to particular sports. Thum played baseball as a kid and often took his son to Dartmouth games; coach Bob Whalen noticed his attendance and asked him to advise the team.

Sue Stuebner'93, a former Dartmouth basketball player and academic counselor in the skills center, began fostering faculty-athlete relations; her successor, Rob Morrissey, enhanced and formalized the program in 1999, creating a handbook for faculty advisors. Morrissey, who also created the Student Athlete Advisory Committee, a group of students who act as the voice for athletes within the athletic administration, looked to similar programs at Princeton and Middlebury for guidance. "The program is casual because we're asking professors to go above and beyond," says Morrissey, acknowledging that not all faculty participants are equally involved with the teams they advise. However, three quarters of the faculty advisors are tenured, senior members of their department, which he believes leads to more freedom to spend time with teams. Listing names of dedicated and active faculty advisors—such as John Pfister (psychological and brain sciences) for women's volleyball, Joseph Nelson (histoiy) and Wey Lundquist '52 (Dickey Center Institute for Arctic Studies) for mens and women's lacrosse, and Robert Gross (biological sciences) and Edward Bradley (classics) for men's ice hockey—Morrissey mentions one professor for nearly every sport, adding, "There are some pretty compelling stories out there."

Coaches and athletes seem to agree. Jeff Cook, head coach of the Ivy League champion men's soccer team, believes that Kang and John Lee (a studio art professor who also counsels the team) have had a "hugely positive effect" and that his players definitely take advantage of Kang's and Lees presence. "They're a tremendous avenue to assist student-athletes in managing their time," he says. "Even though our coaching staff has a very open relationship with the players, sometimes it is easier for them to talk about the sportsschool balance with someone not involved in deciding how much playing time they get during games." When the team made it to the NCAA tournament this pastyear, Cook and Kang drafted a letter to professors to explain player absences. Team members cite it—along with Kang's open- door policy—as enormously helpful. "Professor Kang is always willing to meet with members of the team and give advice on school, soccer and anything else on our minds" says Patrick White '05. "Lastwinter we had lunch a couple of times to talk about resumes and cover letters."

As for his time commitment to the soccer team, Kang expresses no hesitation. He says he publishes as much as he did be- fore he became involved, and he feels that his commitment actually makes him more productive when he is in the office, a skill he and other advisors try to develop in their team members. For Kang, his life at Dartmouth is a dream come true. "When I was in grad school, other students and I used to talk about the old-style jobs at colleges, where you teach in the morning and coach in the afternoon—this hardly exists anymore, and I've managed to create it. It's just awesome."

Throwback Professor Dave Kang enjoysa rare academic life that combines teach-ing, advising and coaching.

Time management, a struggle for every college student, becomes paramount for athletes.

LAUREN ZERANSKI is an editor atAtlas Books in New York City and a regularcontributor to DAM's Campus section.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

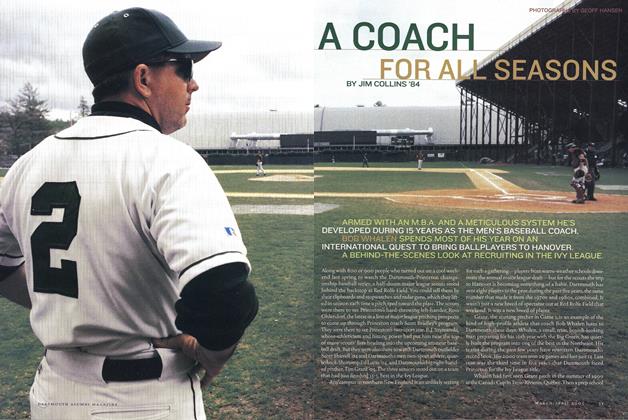

Cover StoryA Coach For All Seasons

March | April 2005 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureIt’s All Downhill, Dude

March | April 2005 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

Feature

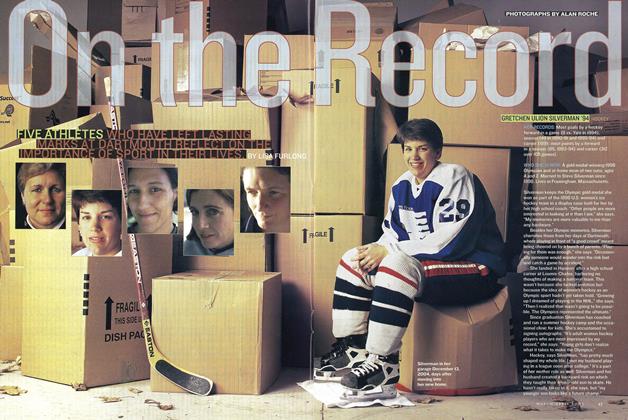

FeatureOn the Record

March | April 2005 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

March | April 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

March | April 2005 By Gray Mercer '83 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut of Control

March | April 2005 By Lance Roberts ’66

Lauren Zeranski ’02

FACULTY

-

FACULTY

FACULTYThe Beat Goes On

Nov/Dec 2011 By Ben Moynihan ’87 -

FACULTY

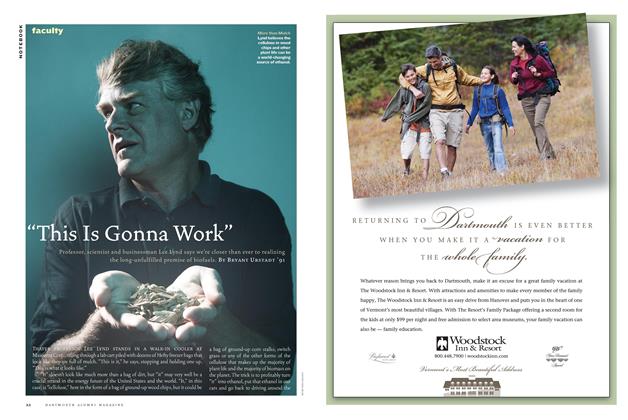

FACULTY“This Is Gonna Work”

Sept/Oct 2009 By Bryant Urstadt ’91 -

FACULTY

FACULTYSeeing and Believing

Nov/Dec 2008 By Carolyn Kylstra ’08 -

FACULTY

FACULTYLearning Curve

July/August 2005 By James Heffernan -

FACULTY

FACULTYPoetic Justice

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14 -

FACULTY

FACULTYThe Truth Is Out There

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14