High Fidelity

How an old fraternity mix tape brought musical enlightenment to one of the last places on campus you’d expect.

Sept/Oct 2006 Brian Corcoran ’88How an old fraternity mix tape brought musical enlightenment to one of the last places on campus you’d expect.

Sept/Oct 2006 Brian Corcoran ’88How an old fraternity mix tape brought musical enlightenment to one of the last places on campus you'd expect.

I HAVE LONG BEEN SOLD ON THE notion that a Dartmouth education encompasses more than just what is taught in the classroom. When I reflect on my time in Hanover, I consistently am reminded that my education was advanced in the most unlikely of places. Such as while standing knee-deep in mung beer in the basement of my fraternity, Phi Delta Alpha.

If it is difficult to imagine circumstances in which the social focus of the average Dartmouth frat house intersects with the official academic mission of the College, bear with me for a moment, and transport yourself back to the much-maligned 1980s. This was an allegedly buttoned-down period that, in the minds of many, is already starting to rival the 1950s as "lamest decade." The Dartmouth of that era had formally shucked its all-male status only a decade before, and the place was struggling with its identity and image. It was in the midst of this struggle that my mental horizons were expanded—by, of all things, a party mix tape.

When I arrived at Dartmouth in 1984, I harbored what I considered an embarrassing secret—I was a confirmed fan of what was then known as New Wave music. I championed bands my straightlaced classmates found bizarre, even frightening, such as U2 and REM. (Hard to believe in hindsight, but that was Dartmouth in the 1980s.) I took my lead for what was cool from the music scenes of Athens, Georgia, or Chapel Hill, North Carolina— college towns that were awash with cutting-edge bands. Hanover, by comparison, as lovely as it was, did not regularly host Sonic Youth or Husker Du, and it certainly lacked the sort of dingy, smoke-filled venues such acts typically played. Instead, the College was at that time ruled by the sounds of "classic rock" or light dance music that could be played at parties. This I generally rebelled against. (I still recall my horror when Bon Jovi's "Livin on a Prayer" blared consistently from the "rock of New England" College radio station in Robinson Hall.) I was, in short, something of a musical snob

My musical world view was challenged after I pledged Phi Delt. It was there I first became acquainted with the legendary single-mix cassette tape intriguingly named "Phi Juke One." A soiled, scratchy copy of that tape probably lies, even now, half hidden toward the back of a dusty shelf of the "tunes closet" at 5 Webster Avenue, like a gold doubloon covered by silt and rotted timbers beneath some wrecked ship of the sunken Spanish Armada, waiting for Robert Ballard to dredge it up.

The origin of Phi Juke One is partly rooted in the mores of the distant Dartmouth past. A long time ago, there was a jukebox in the Phi Delt basement. This jukebox held a variety of songs more appropriate to the Dr. Demento Show than to a fraternity's social space. It featured what one might consider frat-house standards —songs by the Doors, for example, or Steppenwolf's "Magic Carpet Ride," not to mention the de rigueur "Louie Louie"—but coupled them with unexpected one-hit wonders, such as Johnny Horton's forgotten country sing-a-long, "Battle of New Orleans." It even contained tunes by the late, great literary roadhouse bard Warren Zevon—not just "Werewolves of London" but also the less-played but equally great African war song, "Roland the Headless Thompson .Gunner." Zevon was an anomaly, as the majority of the songs contained on Phi Juke One were recorded before the year 1970. Each single was contained on a 45rpm record, an artifact probably as foreign to current undergrads as cuneiform writing or flintlock pistols.

No doubt the jukebox was the epicenter of many a sock hop and ice cream social held in the dank but festive Phi basement during the 1960s and 1970s. However, sometime in the 1970s or early 1980s, wicked marauders attacked the jukebox and partially disabled it. The entire machine was thereafter covered by plywood and a padlock, in the vain hope of protecting it from further dismemberment. Eventually, time and a monthly cascade of stale draft beer did the rest of the damage, flatlining the jukebox for eternity.

But not the 45s it contained. Some enterprising Phi brother had the foresight to preserve many of the 45s onto several mix tapes—foremost among them, Phi Juke One. And it was this act of preservation that gave Phi Juke One its special character. This archivist, if I can call him that, did not just record the songs on tape. No, he put them into an inexplicable order that, after about 1,000 listenings, begins to seem not just reasonable, but ordained. The great "Tequila" (by the song's originators, the Champs) led off the hitparade and was followed by the jarring urgency of "Hawaii 5-0," only to be succeeded moments later by the Four Seasons hit, "Sherry." It was a confusing aural experience with vague psychedelic properties, although it could be enjoyed substance-free. There was an intelligence to the seemingly random juxtaposition of songs on the tape that spoke volumes of the guy who made it, in the same way cave paintings tell us about the advanced brain capacity of Cro-Magnon man.

During my college years Phi Juke One consistently entertained brothers, Dartmouth students and their guests at Phi Delt parties, via a creaky, ready-to-blow sound system wired from the upstairs stereo into the basement itself. The tape provided the soundtrack to pong games, bumbling interaction between the sexes, basement clean-up sessions and joyous reunions alike. And—an important, relevant fact—it was nearly the only officially sanctioned soundtrack to social events held at Phi Delt. So I heard it a lot. A lot.

Of all people, I should have hated Phi Juke One. Its embrace of mostly one-hit wonders and other old songs was utterly inconsistent with my preconceptions about what sort of music was acceptable. Yet I took to Phi Juke One like the French to Jerry Lewis. Perhaps it was my sense of the absurd: There was something enjoyably perverse about Dartmouth students cavorting while Gene Pitney's "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" played in the background, its eerie background fiddle filling the cold New Hampshire night every time someone opened the back door of the basement and confusing the hell out of passers-by on their way back to the Choates. Certainly the mere fact that I was forced to listen to that tape so much contributed to my interest in it. Maybe I was getting more comfortable with my guilty pleasures; I had long loved "Secret Agent Man" by Johnny Rivers but had rarely heard it played in public, let alone at parties where we were supposedly impressing young women with how cool we were to be in a frat to begin with (a supposition that I can readily admit today was greatly misplaced). I also liked how Phi Juke One went against the grain; other houses were playing dance favorites such as Madonna while we played Jimmy Dean (yes, the sausage guy) and his version of "Big Bad John."

In any event, after I'd listened to it about a hundred times on the decrepit house tape player, I really started to "hear" it—then I started to appreciate it and the wonder of its crazy, complex amalgamation of songs that had no business butting up against each other. More than the music, however, I appreciated what the tape represented. The Dartmouth of my era was often obsessed with the notion of diversity and how to incorporate it without losing other valuable aspects of the Dartmouth experience. Phi Juke One was a concrete example of what real diversity could be—a little bit chaotic, a pastiche of styles that ultimately was greater because of its essential variety and randomness. It "opened my ears," and not just to different types of music. I particularly loved the fact that I had become so enlightened (if I may be transcendental for a moment) in one of the last places I would have expected on the Dartmouth campus.

I am not sure if present members of the Phi Delt house appreciate the tape the way I did. At a recent reunion, when I asked that it be played during an informal celebration in the basement, I got a puzzled response from a young Dartmouth guy, followed by the comment, "Oh, you mean the old music?"

"Old but good, my friend," I should have told him with a world-weary grin. Instead, I shoved him aside and jammed the tape into the aforementioned decrepit cassette player.

The tape provided the soundtrack to ponggames, bumbling interaction between thesexes and joyous reunions alike.

BRIAN CORCORAN is partner in a national law firm's Washington, D.C., office. He livesin Maryland with his wife, three children anda vast music collection.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

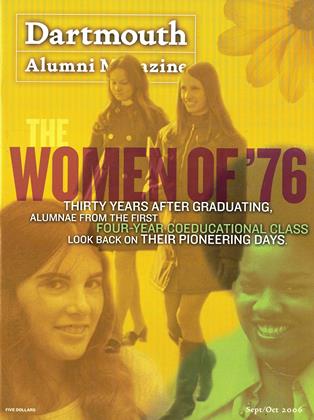

Cover StoryThe Women of ’76

September | October 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

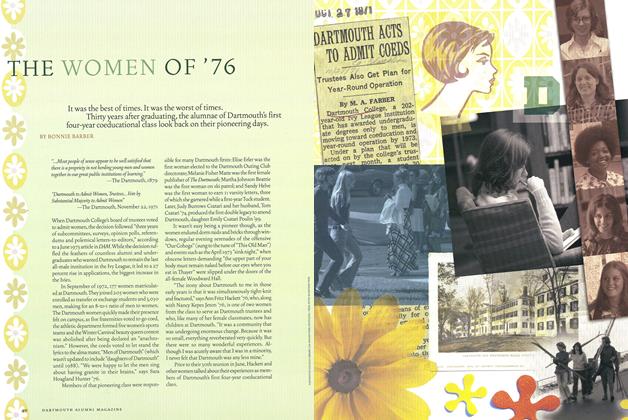

FeatureBand of Brothers

September | October 2006 By RALPH WIMBISH -

Feature

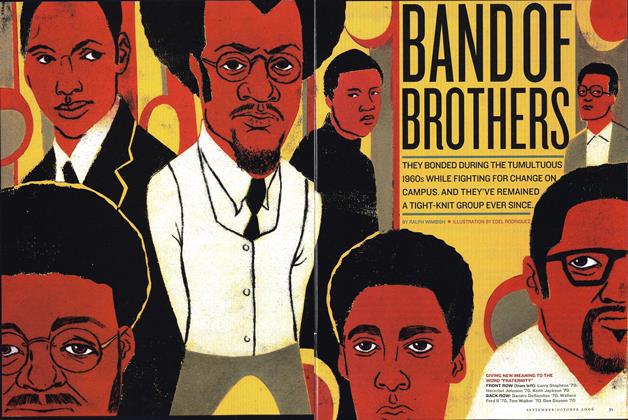

FeatureEd Reckoning

September | October 2006 By ALEXANDER NAZARYAN ’02 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2006 By Russell Hardy' 62 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2006 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SPORTS PUBLICITY -

ALUMNI OPINION

ALUMNI OPINIONDown the Tubes

September | October 2006 By Melissa Lafsky ’00

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBag of Tricks

May/June 2005 By Christopher Kelly ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGoing to the Mat

Sept/Oct 2010 By Diana (Sabot) Whitney ’95 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryThe Places You Can Go

May/June 2001 By Dustin Rubenstein ’99 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYNew Girl in Town

May/June 2012 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYPaddle Tales

APRIL 2025 By KIRA PARRISH-PENNY ’24 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Quantum World

Mar/Apr 2009 By Louisa Gilder ’00