Green Jacket Abroad

A plain and simple sport coat becomes a vestment of myriad memories.

Mar/Apr 2004 Laurence Sterne ’52A plain and simple sport coat becomes a vestment of myriad memories.

Mar/Apr 2004 Laurence Sterne ’52A plain and simple sport coat becomes a vestment of myriad memories.

I WAS AMAZED AT MY 50TH REUNION to find a classmate wearing his original 1952 senior jacket. Seeing it caused me to reflect on my own jacket and its odyssey following my graduation, which was unquestionably inspired by former Dartmouth President John Sloan Dickey '29, the "Great Issues" course of my era and the broad outlook of my liberal arts education.

For seniors in the graduating classes of the 1940s and 19505, it was tradition to order a forest- green sport jacket from a Hanover clothing store. When I was still a freshman, the dark-green jacket worn by strutting upperclassmen commanded awed respect. Twirling Indian- head canes lent additional authority.

When my junior year arrived, the privilege fell on our class to be fitted for the soft flannel jackets. Roommates discussed the financial propriety of this investment. Sacrifices might be made in other directions, but not here.

My jacket was brought forward from among some 700 on the racks. Mass tailoring hadn't helped the fitting. The sleeves were too short and the cloth bunched up between my protruding shoulder blades. My full chest had not been taken into account, so the Ivy- League cut hoisted the cloth an inch or two in the rear. 111-fitting as it was, I strutted in it across the Green. Exact rank went unchallenged with class numerals embroidered on the pocket near the top edge. In keeping with tradition, my white bucks had not been cleaned since freshman year.

Senior year drew to a close and President Dickey sent us off into the world with the words: "In the Dartmouth family, it is never 'goodbye' but 'so long.' God bless you." Echoes of our class chant, "52, rah! rah!" died away. College days were over.

Weeks later, before boarding a bus to boot camp, my mother wrapped her arms about me, a young enlistee clad in his soft flannel jacket. Minutes later the bus roared out of the depot, speeding me into the arms of a Marine drill sergeant in Quantico, Virginia. "It's quite appropriate," I thought on the ride to camp, "to exchange Dartmouth green for the forest green of the Corps. It will be excellent wear for liberties." How wrong I was.

One evening I reported in off liberty wearing my senior jacket. A fellow officer candidate, acting in student capacity as company first sergeant, asked me to relieve him for a few minutes. This I did obligingly. While I was alone, the real company first sergeant rumbled into the office. The "Top" eyed my collegiate attire. His face reddened as his eyes focused on the white embroidered "1952." "Out of uniform!" he shouted. That night, as penalty for assuming those few minutes of duty while still in liberty attire, I stood a triple firewatch—ample time to cut, pick and pull class numerals from the garment.

Relegated to a background position in the wardrobe of a Marine officer, the jacket traveled with me from duty station to duty station. The awful-fitting thing never looked better or worse for cleaning or pressing. Yet it soon fell in line for an even rougher assignment.

My military duties behind me, I scraped together enough savings for a three-month journey to Europe. Awing of the propeller driven Constellation dipped and revealed the Emerald Isle, Ireland. Bright green swamplands along the Shannon rippled in the sunny breeze. My jacket was so many shades off shamrock that it did not occur to me I was wearing the national color. But the pretty colleens crowded round, eager to pose with the young American wearing green. The people of Ireland thought I had worn it especially for them. "It is really only my college blazer," I tried to explain, but with little effect.

A brief stay in Dublin before the trip north to Belfast made clear to me that Eire is green and the North is orange. Nevertheless, natures rich green covers Ulster as impartially as it colors her neighbors in the South. In Belfast friends reasoned that, in my ignorance of the difference in national colors, I had worn green especially for them. In order to show their hospitality they received me even more warmly than if I had blazoned myself in orange.

In England the policeman waved people away while a friend snapped my picture in front of 10 Downing Street. "Bobbies are very considerate," I thought. Later I learned that the courteous London police seldom allow picture- posing in front of the prime ministers residence. I imagine this English policeman thought that the young American in green was of Irish ancestry and went out of his way to impress upon me the practical friendship that flows among our three countries. Perhaps the bobbie was an Irishman!

Copenhagen, Berlin, Paris, Vienna. Everywhere I traveled, people took the Dartmouth green into their hearts. On an alpine trail, as I was passing a green-hatted Tyrolean climber, it brought forth a crisp, "Gruss Gott." We did not need to know each others language. In that moment of passing, green, the color of nature, bound us together.

Some months later, graduate student life catapulted me from pinetopped Austrian mountains to a palm-treed California campus. My senior jacket was now threadbare at sleeves end. It fit no better than the day it came off the racks five years before. Yet it remained part of my daily wear to class, church and on dates—until word came one day that a flood had inundated a small western city. Then followed pleas to help supply clothes for the evacuees. I laid the jacket out each day. Finally it joined the other contributions.

Jacket and traveler have long since parted. Yet whenever traveling abroad, I always think of myself as cloaked in the green.

LAURENCE STERNE, a Ph.D. in English literature,is a retired psychoanalyst living in NewYork City. He wrote a version of this piece in1957 for The Christian Sciences-Monitor while working there as a copy boy. Adapted withpermission. Copyright® 1957 The Christian Science Monitor. All rights reserved.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

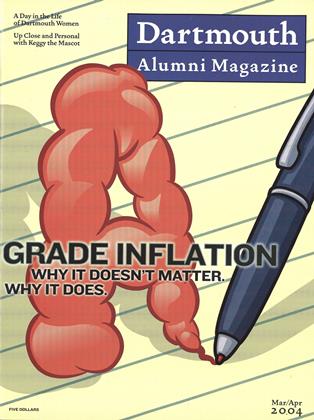

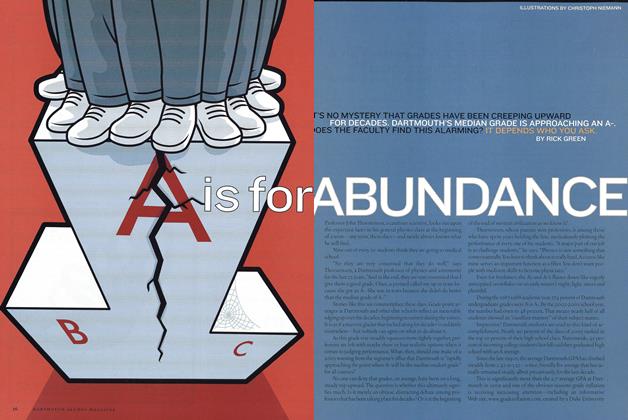

Cover StoryA is for Abundance

March | April 2004 By RICK GREEN -

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

March | April 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

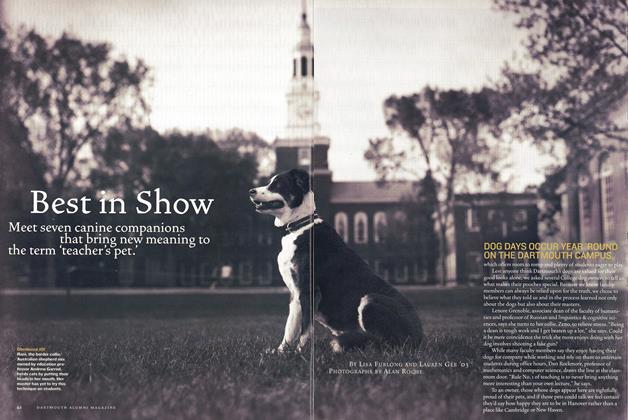

FeatureBest in Show

March | April 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

March | April 2004 By David C. Kang -

From the Dean

From the DeanThe Fourth ‘R’

March | April 2004 By Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61

Laurence Sterne ’52

Personal History

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHigh Fidelity

Sept/Oct 2006 By Brian Corcoran ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

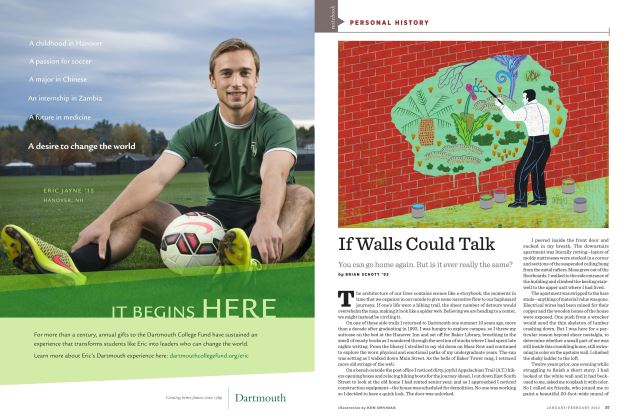

PERSONAL HISTORYIf Walls Could Talk

JAnuAry | FebruAry By BRIAN SCHOTT ’93 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLove and Empire

July/August 2011 By Courtney Cook ’93 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYClutch Situation

July/Aug 2013 By Daisy Alpert Florin ’95 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGear Shift

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2022 By DANIELLE FURFARO -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYNothing In Common

July | August 2014 By LYNN HOLLENBECK ’83