Border Patrol

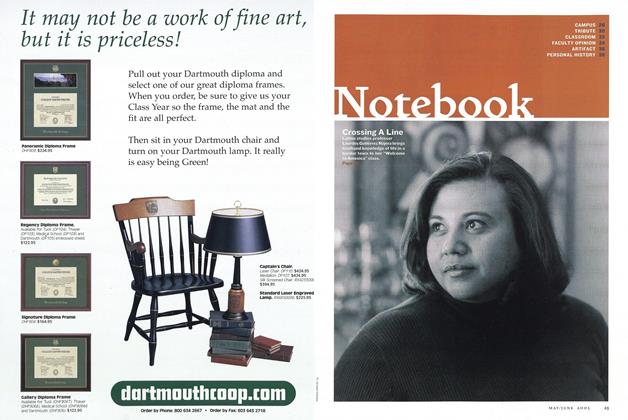

A Mexican-born professor draws on her own experience to teach students that borders are more than just lines drawn on a map.

May/June 2005 Julie Sloane ’99A Mexican-born professor draws on her own experience to teach students that borders are more than just lines drawn on a map.

May/June 2005 Julie Sloane ’99A Mexican-born professor draws on her own experience to teach students that borders are more than just lines drawn on a map.

GROWING UP IN NOGALES, MEXICO, in the 19705, Lourdes Gutierrez Najera lived in a house across the street from the U.S. border that separated her town from Nogales, Arizona. She remembers crossing into Arizona often, to shop for clothes or just run around. Sometimes her mother would go grocery shopping in Arizona, call out to her through the fence that marked the border, and toss the bags over for her daughter to carry home. To cross the border, Gutierrez did what everyone else did: She walked through the border patrol checkpoint and said, "American." She wasn't an American at the time, but in those days nobody seemed to mind.

At age 8 Gutierrez and her family moved to Los Angeles. She became a U.S. citizen in 1996 while working toward her Ph.D. in anthropology and social work at the University of Michigan. There she entered a'competition of sorts to design a new course. The result was "Welcome to Amexica: Comparative Perspectives on the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands," which Michigan approved her to teach in the summer of 2003. This fall she brought the course to Dartmouth as a visiting lecturer in the Latino studies department, where she also teaches Latino Studies 44, about the varied experiences of Latino migrants.

"Welcome to Amexica" gets its name from a Time magazine cover story in June 2001 that heralded a borderless future in which Mexico and the United States might seamlessly blend into one another. Sure, drugs and illegal immigration are problems, but the article expressed optimism that with Latinos now the biggest minority in the country and a former Texas governor now president, the southern U.S. border might become more like its northern one,"basically defended by a couple of fire trucks." Three months later the cover of Time was a photo of a plane crashing into the World Trade Center, and the U.S.Mexico border was in the news for a different reason—as a gateway for terrorists.

It's undeniably a busy place. The U.S. government recorded 49 million pedestrian crossings into the United States from Mexico in 2003. Another 194 million passengers entered in personal cars and trucks. These figures include only legal crossings at government checkpoints. It's widely assumed that millions more cross illegally. For Americans and Mexicans alike, says Gutierrez, the shared border evokes images of prostitution, drugs, alcohol and poverty, all amid piles of multicolored straw sombreros. Violence in Ciudad Juarez or debaucheiy in Tijuana are all most Americans know of the border. But to base our experience on those images, she says, doesn't begin to scratch the surface of the complexity of life there. "One thing I try to get across in my class is that the border is a continually changing place," she says. "It's dynamic. It's more than just a line—it's a place where people live and thrive."

Early in the course Gutierrez spends a week delving into the history of the U.S.-Mexico border. The location of the border has evolved with the expansion of the United States over time, as has the U.S. attitude toward it. The U.S. Border Patrol came into being in 1924, not so much to exclude Mexicans as to keep out the Chinese and Europeans. Throughout the boom times of the 1920s the border was virtually an open door for Mexicans to labor in agriculture or on the railroads. When the Depression hit and jobs became scarce, Mexicans became undesirables and the U.S. government worked to repatriate them to Mexico. The pendulum swung back during World War II, when Mexican laborwas again welcomed. "My grandmother used to cross back and forth in the 1940s for migrant farm work in Texas," says Gutierrez. "She said that when times were tough, the border patrol would just turn their back to you. At other times the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service would come and get you from your work. Even when U.S. policy on paper was the same, sometimes the door was open and sometimes it was closed." One constant contradiction: "We want the labor; we don't want the people."

Many of the 19 students in Gutierrez's fall class come from cities and towns near a U.S. border—San Diego, Ann Arbor, Buffalo, New York—while several are of Mexican descent. All of them have in common another border: Dartmouth, Gutierrez points out, is also a border town in several ways. Most obviously, it is on the border between Vermont and New Hampshire. Cross the Connecticut River, and laws, taxes and state identity are all different. But Dartmouth also illustrates another theme of the course: Borders are not always literal lines on a map. "Hanover and Norwich are not representative of the wider community around us," Gutierrez points out. "High property values have the capacity to define who is included and excluded. In a way, the wealth of this area is also a kind of border." In her class Gutierrez holds discussions on how Mexicans living in the United States continue to experience more abstract versions of the border as they negotiate two different cultures. Simply changing geography doesn't ease language barriers and prejudice against Mexicans, which can exclude them from American life as much as any fence.

Each week of the course brings a new theme, and Gutierrez often uses documentary films to introduce them, During week five she introduces the idea of transnational communities by screening The Sixth Section, a film about how Mexican immigrants in Newburgh, New York, support their families in Puebla, Mexico, by wiring home cash. "Most communities in Mexico are dependent on migrant remittances," says Gutierrez, whose own research focuses on the transnational mi- grant community split between Los Angeles and Yalalag, Oaxaca. "Billions of dollars go back to Mexico through migrants. It's very important to the Mexican economy."

In the United States the presence of those immigrants, many of them undocumented, causes a great deal of resentment and racism. In week seven Gutierrez shows the 2004 documentary Farmingville, about a town in New York where two Mexican laborers were nearly beaten to death by white supremacists. Border conflict, it shows, doesn't necessarily take place in a border town. She also screens the 1991 film Natives: ImmigrantBashing on the Border, a look at anti-immigration activists in California who feel that illegal immigrants drain community resources and boost crime rates. "The students just laugh through it," says Gutierrez. "The xenophobia seems so absurd to them. But it presents an important reality and it's very provocative for stimulating discussion." Should these immigrants be denied health care and education because they aren't citizens? Do legal rights trump human rights?

Week nine of the class opens the discussion to other international borders. Andrew Hamilton '04 returned to Hanover to present his anthropology senior thesis on the decades of conflict along the Irish border. Mishuana Goeman '94, appointed this year as an assistant professor of Native-American studies and English at Dartmouth, lectured on the borders of the Iroquois nation, which span and overlap the U.S.-Canada border, and what that means for the nations member tribes.

Gutierrez hopes her students will follow more closely as the U.S. borders make news. In January leaked CIA documents showed that the U.S. has recently turned away dozens of suspected terrorists at the Canadian border, a sign of increased fortification of both U.S. borders. That same month the Mexican government began issuing a cartoon guide instructing its citizens how to stay safe when crossing into the United States, much to the outrage of some Americans. "The story continues," says Gutierrez. "I hope that the reading and discussions have brought my students enough knowledge to begin to break down stereotypes and see the complexity of border issues."

Welcome to Amexica Children runalong opposite sides of the U.S.-Mexicoborder fence in Calexico, California.Border issues are addressed in a newLatino studies class.

JULIE SLOANE is a writer at Fortune Small Business magazine in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

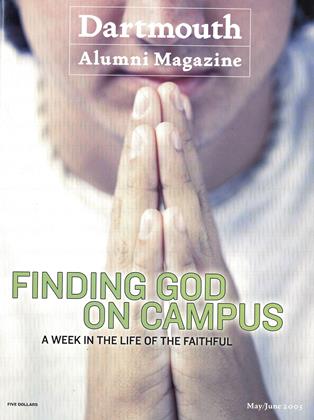

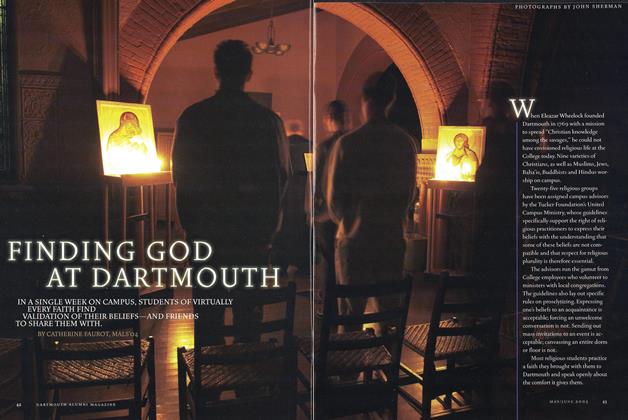

Cover Story

Cover StoryFinding God at Dartmouth

May | June 2005 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’04 -

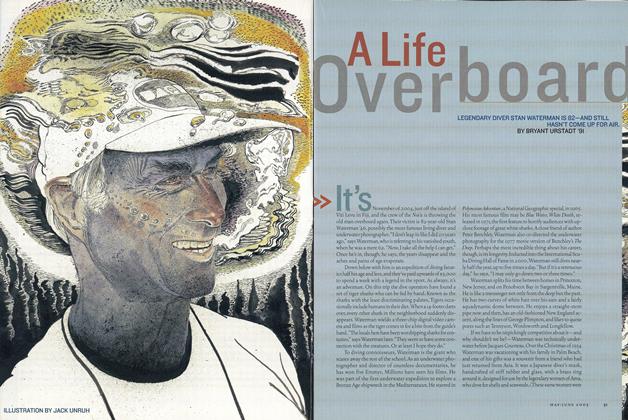

Feature

FeatureA Life Overboard

May | June 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

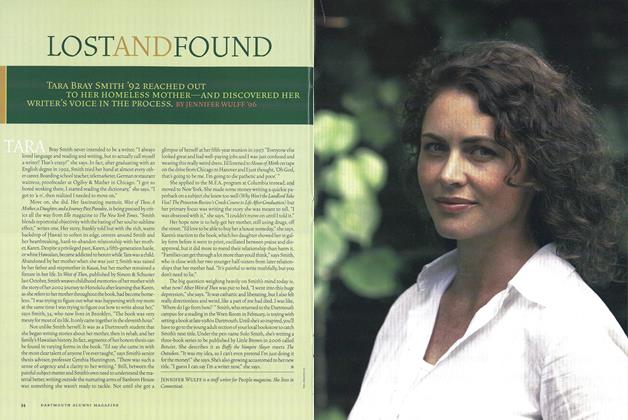

Feature

FeatureLost and Found

May | June 2005 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2005 By Olivia Britt '00 -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONShiny Bubble

May | June 2005 By JOHN H. VOGEL JR.

Julie Sloane ’99

-

Article

ArticleHealing Outside the Hospital

MAY 2000 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Classroom

ClassroomLearning By Doing

May/June 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Human Condition

Sept/Oct 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNew Dimensions

Nov/Dec 2005 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Cover Story

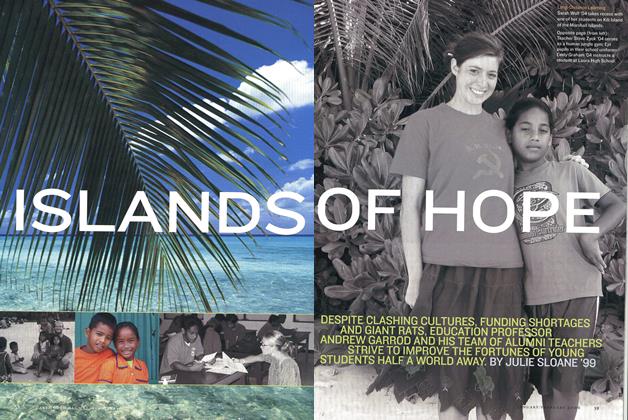

Cover StoryIslands of Hope

Jan/Feb 2006 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWarring Factions

Jan/Feb 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNuts and Bolts

Mar/Apr 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMAll About Algorithms

Sept/Oct 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhen Nations Collide

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By JUDITH HERTOG -

Classroom

ClassroomLearning By Doing

May/June 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Art and Science of Group Dynamics

Nov/Dec 2002 By Karen Endicott