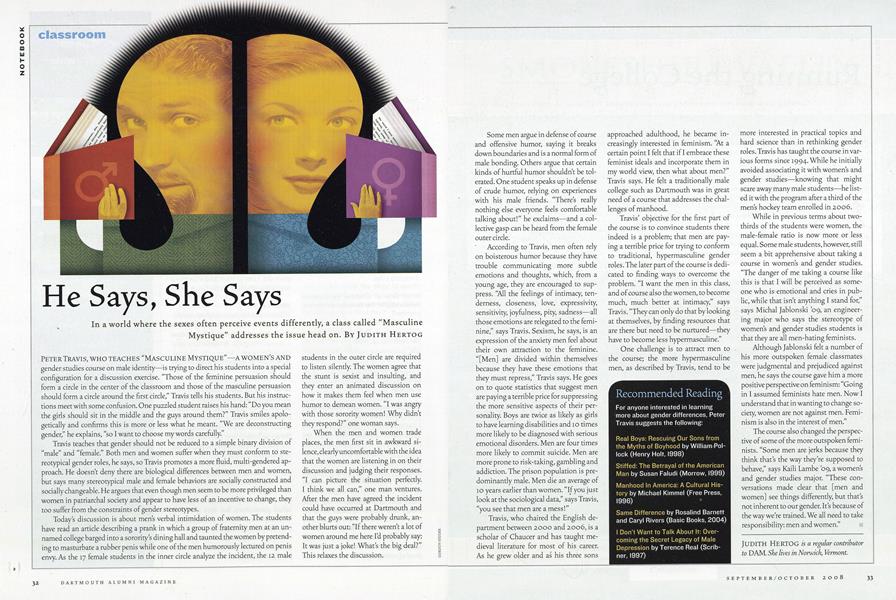

He Says, She Says

In a world where the sexes often perceive events differently, a class called “Masculine Mystique” addresses the issue head on.

Sept/Oct 2008 Judith HertogIn a world where the sexes often perceive events differently, a class called “Masculine Mystique” addresses the issue head on.

Sept/Oct 2008 Judith HertogIn a world where the sexes often perceive events differently, a class called "Masculine Mystique" addresses the issue head on.

PETERTRAVIS, WHO TEACHES "MASCULINE MYSTIQUE"—A WOMEN'S AND gender studies course on male identity—is trying to direct his students into a special configuration for a discussion exercise. "Those of the feminine persuasion should form a circle in the center of the classroom and those of the masculine persuasion should form a circle around the first circle," Travis tells his students. But his instructions meet with some confusion. One puzzled student raises his hand: "Do you mean the girls should sit in the middle and the guys around them?" Travis smiles apologetically and confirms this is more or less what he meant. "We are deconstructing gender," he explains, "so I want to choose my words carefully."

Travis teaches that gender should not be reduced to a simple binary division of "male" and "female." Both men and women suffer when they must conform to stereotypical gender roles, he says, so Travis promotes a more fluid, multi-gendered approach. He doesn't deny there are biological differences between men and women, but says many stereotypical male and female behaviors are socially constructed and socially changeable. He argues that even though men seem to be more privileged than women in patriarchal society and appear to have less of an incentive to change, they too suffer from the constraints of gender stereotypes.

Today's discussion is about mens verbal intimidation of women. The students have read an article describing a prank in which a group of fraternity men at an unnamed college barged into a sorority's dining hall and taunted the women by pretending to masturbate a rubber penis while one of the men humorously lectured on penis envy. As the 17 female students in the inner circle analyze the incident, the 12 male students in the outer circle are required to listen silently The women agree that the stunt is sexist and insulting, and they enter an animated discussion on how it makes them feel when men use humor to demean women. "I was angry with those sorority women! Why didn't they respond?" one woman says.

When the men and women trade places, the men first sit in awkward silence, clearlyuncomfortable with the idea that the women are listening in on their discussion and judging their responses. "I can picture the situation perfectly. I think we all can," one man ventures. After the men have agreed the incident could have occurred at Dartmouth and that the guys were probably drunk, another blurts out: "If there weren't a lot of women around me here I'd probably say: It was just a joke! What's the big deal?" This relaxes the discussion.

Some men argue in defense of coarse and offensive humor, saying it breaks down boundaries and is a normal form of male bonding. Others argue that certain kinds of hurtful humor shouldn't be tolerated. One student speaks up in defense of crude humor, relying on experiences with his male friends. "There's really nothing else everyone feels comfortable talking about!" he exclaims—and a collective gasp can be heard from the female outer circle.

According to Travis, men often rely on boisterous humor because they have trouble communicating more subtle emotions and thoughts, which, from a young age, they are encouraged to suppress. "All the feelings of intimacy, tenderness, closeness, love, expressivity, sensitivity, joyfulness, pity, sadness—all those emotions are relegated to the feminine," says Travis. Sexism, he says, is an expression of the anxiety men feel about their own attraction to the feminine. "[Men] are divided within themselves because they have these emotions that they must repress," Travis says. He goes on to quote statistics that suggest men are paying a terrible price for suppressing the more sensitive aspects of their personality. Boys are twice as likely as girls to have learning disabilities and 10 times more likely to be diagnosed with serious emotional disorders. Men are four times more likely to commit suicide. Men are more prone to risk-taking, gambling and addiction. The prison population is predominantly male. Men die an average of 10 years earlier than women. "If you just look at the sociological data," says Travis, "you see that men are a mess!"

Travis, who chaired the English department between 2000 and 2006, is a scholar of Chaucer and has taught medieval literature for most of his career. As he grew older and as his three sons approached adulthood, he became increasingly interested in feminism. "At a certain point I felt that if I embrace these feminist ideals and incorporate them in my world view, then what about men?" Travis says. He felt a traditionally male college such as Dartmouth was in great need of a course that addresses the challenges of manhood.

Travis' objective for the first part of the course is to convince students there indeed is a problem; that men are paying a terrible price for trying to conform to traditional, hypermasculine gender roles. The later part of the course is dedicated to finding ways to overcome the problem. "I want the men in this class, and of course also the women, to become much, much better at intimacy," says Travis. "They can only do that by looking at themselves, by finding resources that are there but need to be nurtured—they have to become less hypermasculine."

One challenge is to attract men to the course; the more hypermasculine men, as described by Travis, tend to be more interested in practical topics and hard science than in rethinking gender roles. Travis has taught the course in various forms since 1994. While he initially avoided associating it with women's and gender studies—knowing that might scare away many male students—he listed it with the program after a third of the men's hockey team enrolled in 2006.

While in previous terms about twothirds of the students were women, the male-female ratio is now more or less equal. Some male students, however, still seem a bit apprehensive about taking a course in women's and gender studies. "The danger of me taking a course like this is that I will be perceived as someone who is emotional and cries in public, while that isn't anything I stand for," says Michal Jablonski '09, an engineering major who says the stereotype of women's and gender studies students is that they are all men-hating feminists.

Although Jablonski felt a number of his more outspoken female classmates were judgmental and prejudiced against men, he says the course gave him a more positive perspective on feminism: "Going in I assumed feminists hate men. Now I understand that in wanting to change society, women are not against men. Feminism is also in the interest of men."

The course also changed the perspective of some of the more outspoken feminists. "Some men are jerks because they think that's the way they're supposed to behave," says Kaili Lambe '09, a women's and gender studies major. "These conversations made clear that [men and women] see things differently, but that's not inherent to our gender. It's because of the way we're trained. We all need to take responsibility: men and women."

JUDITH HERTOG is a regular contributorto DAM. She lives in Norwich, Vermont.

Recommended Reading For anyone interested in learningmore about gender differences, PeterTravis suggests the following: Real Boys: Rescuing Our Sons from the Myths of Boyhood by William Pollock (Henry Holt, 1998) Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man by Susan Faludi (Morrow, 1999) Manhood In America: A Cultural History by Michael Kimmel (Free Press,1996) Same Difference by Rosalind Barnettand Caryl Rivers (Basic Books, 2004) I Don't Want to Talk About It: Overcoming the Secret Legacy of Male Depression by Terence Real (Scribner, 1997)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

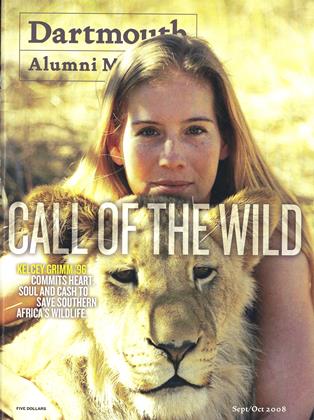

COVER STORY

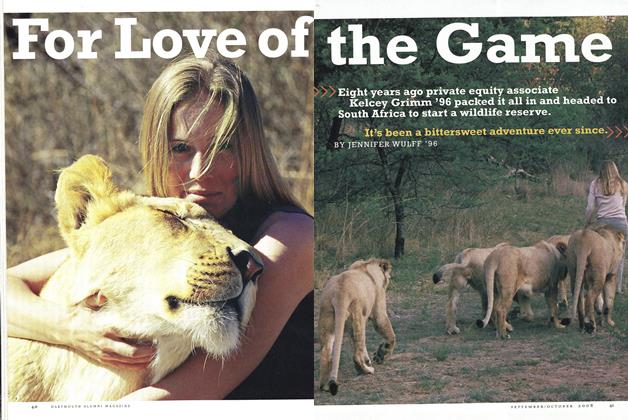

COVER STORYFor Love of the Game

September | October 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

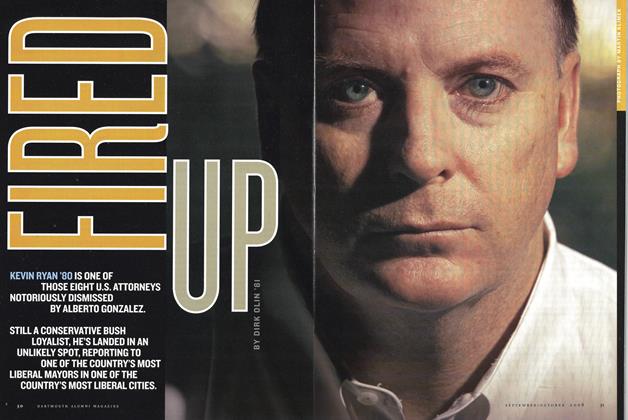

FeatureFired Up

September | October 2008 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

FeatureIn Their Own Words

September | October 2008 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2008 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

September | October 2008 By Kristen STromber '94 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2008 By BONNIE BARBER

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

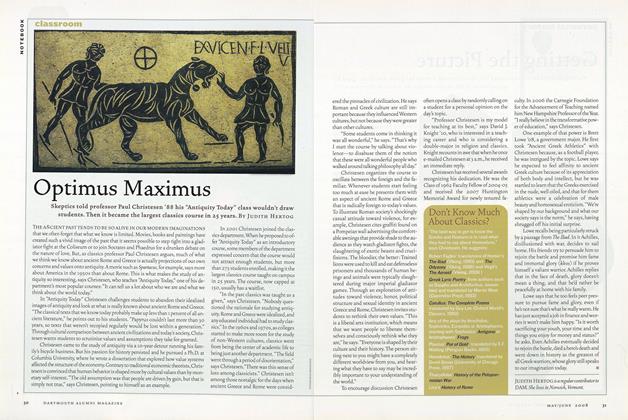

CLASSROOMOptimus Maximus

May/June 2008 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNuts and Bolts

Mar/Apr 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMReality Show

NovembeR | decembeR By JUDITH HERTOG -

Classroom

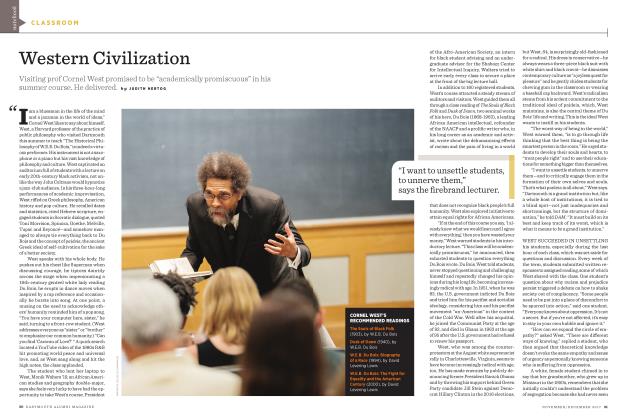

ClassroomWestern Civilization

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By JUDITH HERTOG -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMInspired by Salvador

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14

Judith Hertog

-

Article

ArticleArt of the "Extreme"

May/June 2007 By Judith Hertog -

Article

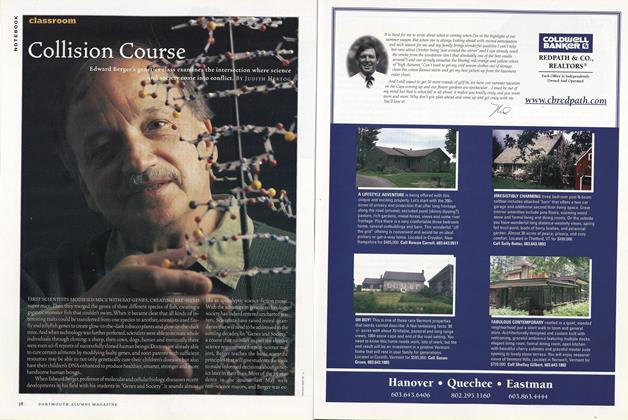

ArticleCollision Course

Sept/Oct 2007 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNuts and Bolts

Mar/Apr 2010 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMSpeaking to the Future

May/June 2011 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMRich Man, Poor Man

Sept/Oct 2011 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMSea of Uncertainty

MAY | JUNE 2014 By JUDITH HERTOG

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMA Body in Motion

MAY | JUNE 2018 By GEORGE M. SPENCER -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMMaking A Case

July/Aug 2013 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMSea of Uncertainty

MAY | JUNE 2014 By JUDITH HERTOG -

Classroom

ClassroomThe Human Condition

Sept/Oct 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMInspired by Salvador

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM ’14