Shiny Bubble

As housing prices skyrocket and real estate speculators jump in, there is good reason to anticipate a crash.

May/June 2005 JOHN H. VOGEL JR.As housing prices skyrocket and real estate speculators jump in, there is good reason to anticipate a crash.

May/June 2005 JOHN H. VOGEL JR.As housing prices skyrocket and real estate speculators jump in, there is good reason to anticipate a crash.

ALTHOUGH THE EXISTENCE OF A housing bubble can be proven only after it has burst, I believe we're in one. Others argue that prices will remain high for reasons ranging from the ever-increasing cost of housing materials to the willingness of people to make ever-greater sacrifices in order to live in desirable neighborhoods.

and doubled in value in March 2000— just before the market crashed. The fact is that families are now stretched beyond their capacity. The ratio of median incomes to median housing prices is substantially worse than it has been in 30 years. For a while appreciation in house prices could be explained by the decline in interest rates, but during the last 12 months the only explanation for the record appreciation in home prices is the kind of irrational exuberance that fueled the technology bubble at the end of the 1990s. It is also noteworthy that economic bubbles do not always slow down; they may speed up just before they pop. That s what happened with the technology bubble, when a record number of initial public offerings came on the market

I believe there is a parallel between the current residential market and the commercial real estate bubble of the late 1980s and early 19905. During that time period the price of office buildings continued to rise despite a glut of office space and a decline in rental rates. When that bubble burst, the value of office buildings across the United States fell by 50 percent. Since 1995 housing prices across the United States have increased by 60 percent. In some major markets, such as the New York metropolitan area, median home prices have risen each year for the last five by double-digit rates ranging from 11.1 percent to around 20 percent. These increases cannot be sustained. What we have learned from past bubbles is that they tend to last longer and end faster than anyone expects.

Another indicator that we're in a bubble is the pervasive trading or speculative mentality that is driving the housing market. Overall home sales last year reached a record 72 million, which is 50 percent higher than the average number of home sales in the mid-19905. This increase in home sales is mostly a result of speculators becoming more active in the housing market. In an extreme example we hear about purchasers in hot markets such as Miami, where they buy condominiums based on pictures they have seen on the Internet. Forty to 70 percent of these condo buyers never expect to live in their properties but are planning to resell them before construction is completed.

This kind of speculation is not a new phenomenon. In 1637 tulip bulbs that once sold at one or two guilders quickly got bid up to more than 50 times that amount before anyone knew if the bulb would produce a high-quality flower. The tulip bulb bubble is a classic example of a disconnect between value and pricing. The technology boom followed the same pattern, with day traders speculating in stocks without knowing what the company actually did. As buyers line up to buy condominiums in Washington, D.C., and watch the prices rise several times a day, one senses that the same mentality is at work in the housing market.

During the last year a slight uptick in mortgage rates caused homeowners to switch to adjustable-rate mortgages. In California more than 60 percent of new mortgages written during the last 12 months were adjustable-rate mortgages. Nationwide, 37 percent were adjustable. It is also noteworthy that 30 percent of these mortgages were for 90 percent or more of the purchase price. A significant increase in mortgage rates, which many experts predict will happen, will not only make it difficult for new buyers to get into the market but also will force existing homeowners to default on their loans.

In its successful effort to increase the homeownership rate in the United States to record levels, the federal government has encouraged financial institutions to loosen their standards and be more creative in their underwriting and product offerings. The old rule that the monthly payment of principle, interest, taxes and insurance should not exceed 28 percent of a family's income has been replaced by an elaborate computer model that factors in a family's net worth, credit score and other criteria. In one case, I saw a local lender feed information into his computer model, which then allowed him to approve a loan that would consume 87 percent of his customer's gross pay. Obviously, this customer would have a hard time paying for food, clothing, transportation and other necessities with that much of her income going to housing.

As we look back on the technology bubble, it is clear one of the things that fostered such high stock prices was the availability of large amounts of cash and credit from banks, venture capitalists and the stock market. By analogy, the housing boom has been fueled by both low interest rates and easy access to credit. If default rates begin to climb, mortgage-underwriting standards will tighten. This will create a double whammy, in which housing defaults increase the supply of housing and tighter credit reduces the number of buyers.

Without the "wealth effect" from housing appreciation and without easy access to home equity lines of credit, consumer spending is likely to decline. This has happened in the Netherlands. After three years of declining housing values, there was a 1.2 percent drop in consumer spending that drove the country into recession.

An even more troubling prospect is that the bursting of the housing bubble will cause families to lose their homes. Savings rates in the United States have declined from 8 percent of household incomes to less than 2 percent during the last 12 years, as the combination of houssume more and more of a family's disposable income. Surveys of homeowners show that many households have only a very small cushion of savings with which to protect their homes from foreclosure. With a large federal deficit and the problems at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government will have a hard time finding the resources to help families hold onto their homes. Even Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan has begun to voice concern about the fragility of our housing finance system in general and about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in particular.

Just as the United States foreshadowed what happened globally with the commercial real estate market a decade ago, Australia may tell us something about what will happen to the residential market here. In 2004 housing prices in Sydney fell 16 percent, and houses now remain on the market 40 percent longer than they did a year ago. In Tokyo housing prices still have not fully recovered from their precipitous decline 15 years ago.

Housing is different than other investments. For most people it is the largest investment they will ever make as well as the place where they will live. In recent years an increasing number of people have viewed it as a "can't lose" investment—and taken on more debt than they can comfortably afford. When the housing bubble bursts, speculators and people who are over-leveraged will be forced out of the market and balance will once again be restored between housing as an investment and housing as shelter. In that regard, it is easy to predict that the first and hardest hit property type will be condominiums in hot markets.

Prudent government policy would dictate that we should begin planning and setting aside money to deal with the housing bubble. I am reminded of the early 1980s, when the savings banks and savings and loans got into trouble because of high interest rates. It was estimated that it would have cost the government $40 billion to bail them out. Instead, the government loosened the rules and, 10 years later, the bailout cost $5OO billion. If housing prices decline rapidly we will need a significant infusion of capital to support our housing finance system. More importantly, we will need significant capital and well-constructed programs to keep people from losing their homes.

JOHN H. VOGEL Jr. is adjunct professor atthe Tuck School of Business and associate faculty director of the James M.Allwin Initiativefor Corporate Citizenship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

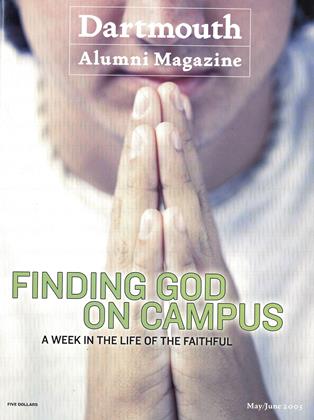

Cover Story

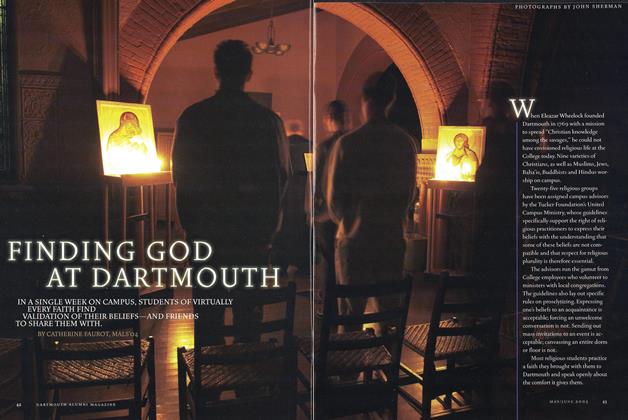

Cover StoryFinding God at Dartmouth

May | June 2005 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS ’04 -

Feature

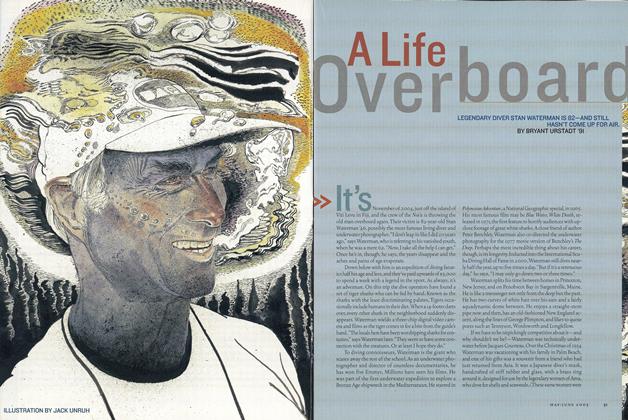

FeatureA Life Overboard

May | June 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

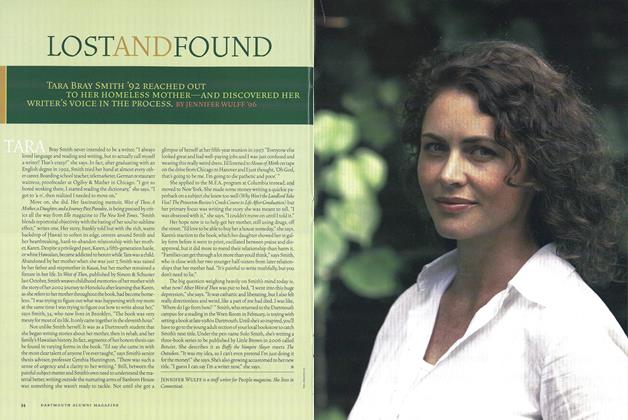

FeatureLost and Found

May | June 2005 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2005 By THOMAS AMES JR. '74 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2005 By Olivia Britt '00 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBag of Tricks

May | June 2005 By Christopher Kelly ’96

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTo Be a Lazy European

Jan/Feb 2007 By Bruce Sacerdote ’90 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

Mar/Apr 2004 By David C. Kang -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONA Sorry State of Affairs

Jan/Feb 2008 By Jennifer Lind -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONSpeaking in Tongues

May/June 2006 By John Rassias ’49A, ’76A -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July/August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionCan You Believe It?

May/June 2004 By Walter Sinnott-Armstrong