The Human Condition

With his storytelling lecture style, popular biology professor Lee Witters brings the subject to life.

Sept/Oct 2004 Julie Sloane ’99With his storytelling lecture style, popular biology professor Lee Witters brings the subject to life.

Sept/Oct 2004 Julie Sloane ’99With his storytelling lecture style, popular biology professor Lee Witters brings the subject to life.

IT'S A MINUTE BEFORE THE END OF class. Moore Filene Auditorium thrums with bags zippering and coats rustling as 210 students release 64 minutes worth of pent-up movement. Lee Witters brings them all back with three little words. "What's with farting?"

Silence. "Benjamin Franklin once said that digestion creates 'a great quantity of wind.' But what causes this problem of flatus?" Then the laughter erupts. In Biology 2: "Human Biology" the finale to Witters' lecture on the digestive system is a real crowd pleaser.

Witters, an endocrinologist, came to Dartmouth from Harvard in 1984. In addition to teaching Medical School students and running an active research lab (where he studies how a cell monitors its own energy level), Witters teaches a full slate of undergraduate courses: "Human Biology" in the fall, "The Biology and Politics of Starvation" in the winter and "Endocrinology" in the spring. Since 1994 he has also been the primary premed advisor to hundreds of undergraduates through Dartmouth's Nathan Smith Pre- medical Society, which provides un- dergrads with advice and shadowing programs. To accommodate his growing role at the College, Witters stopped see- ing patients in 1999.

The first third of Bio 2 focuses on the scientific fundamentals of human biology, covering staples such as cell metabolism and the chemistry of DNA. It may be less exciting than the remainder of the course, which turns to organ systems and diseases, but Witters livens up the subject matter. In one lesson the class stands up and acts out the mitochondria's electron transport chain, with some students passing ping pong balls, balloons and water bottles to represent protons and electrons, oxygen and water while others, designated as enzymes, dance in the aisles. In his reproduction lecture, Witters shows a cartoon of sperm fertilizing an egg cell to the sounds of—what else?—"Sexual Healing" by Marvin Gaye.

The class relies heavily on technology, with PowerPoint slides accompanying every lecture. Embedded within are video clips—the view of a colonoscopy from inside the large intestine, a pancreatic cell secreting insulin, an MRI of the brain. (Students can download both the slides and video from the courses Web site.) Witters uses the X hours to show fulllength films such as Dying to Be Thin, a documentary on anorexia, and KillerDisease on Campus, which explores deadly outbreaks of bacterial meningitis.

Witters' wife, Judy, is a professional storyteller, and Witters himself is adept at weaving stories into his lectures. He tells the tale of Santorio Santorio, a contemporary and friend of Galileo, who sat on a scale for 30 years to prove that we lose weight through perspiration. He recounts how John Kellogg intended his corn flakes to reduce libido. 'As we head into the weekend," Witters tells his students, "you mayor may not want a bowl of corn flakes. You may or may not want to give a bowl of corn flakes to somebody else." (They laugh.) Even a basic tour of the digestive systems organs follows a protagonist, a green M&M, from the mouth to the intestines. Lectures are also full of topnotch cocktail party trivia: Doctors can remove seven-eighths of the liver and the whole thing will grow back. The small intestine has the surface area of a tennis court. Fidgeting is a legitimate way of burning calories.

The course changes slightly each year to reflect current events. Last year mad cow disease, anthrax, SARS and smallpox made it into the syllabus. This year the Atkins and South Beach diets join a beefed-up lecture on obesity.

"I think human biology ought to be a requirement to graduate from college," says Witters. "You could take math or physics or geology and do nothing with them the rest of your life, but you will never escape your own biology." While we will all have to deal with health care in a personal way, Dartmouth graduates, Witters points out, often tackle issues of human biology in a more public venue, as voters, politicians, judges or nonprofit workers. Famine, Witters offers, is not' only a biological problem, but a social, political and economic one."I actually see this as a language course," says Witters. "The students are learning the language of human biology so that they can read an article in a magazine or newspaper or have a conversation and understand what hormone replacement therapy means, what cancer means, what a stomach ulcer is."

Witters' approach is popular with students—and not just because his class has no mandatory reading. ("I can't find a textbook that fits the course in away I'd like so I rely on my own materials," says Witters. "It's an extensive syllabus.") The class of 2002 chose him as its Class Day speaker and the Order of Omega, the Greek system's academic honor society, recently named him its outstanding professor for 2004. Witters, for his part, enjoys teaching them. While medical students are more vocationally focused, Witters finds that undergraduates come to his class with a sense of awe. "They haven't lost their 'Gee whiz. Isn't that cool?' or 'Can we go beyond that and talk about what that might mean?' " he says. Every Memorial Day Witters invites students to his farm in Vermont for a barbecue. "I'm proving to the students I don't actually live in my office," he says. About 75 come every year to walk in the woods and meet the horses and chickens.

So what is with farting? It comes down to a trisaccharide sugar called raffinose, which is abundant in beans. Humans don't have the enzyme that metabolizes raffinose, but the bacteria in our colons do, and breaking down these sugars creates gas. Beano, an anti-gas pill available at the drugstore, contains that missing enzyme, and Witters wraps up the lecture presenting data from a 1994 study that proved the pill's effectiveness. (This is, after all, a science course.) "Beano," Witters concludes, "will indeed make you a more acceptable social animal." Smiles on their faces, the students disperse.

Ceil Job “You will never escape yourown biology,” says Witters, who believeshuman bio should be a required course.

JULIE SLOANE is a writerat Fortune Small Business magazine in New York City.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

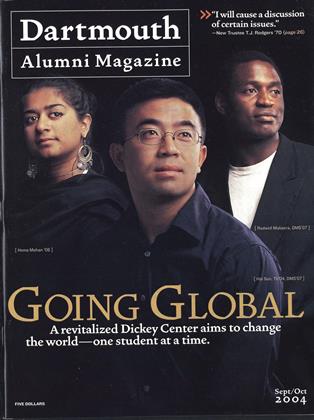

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

September | October 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

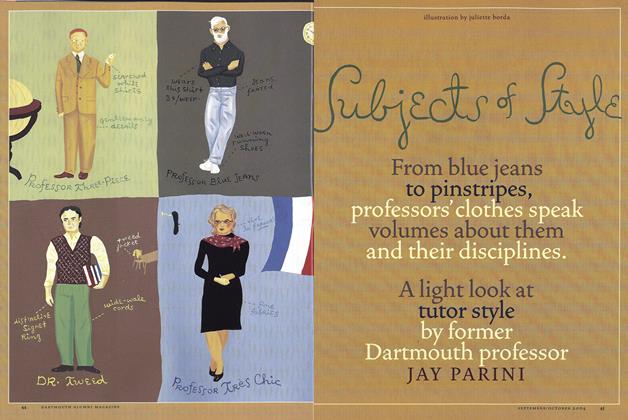

FeatureSubjects of Style

September | October 2004 By JAY PARINI -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

September | October 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Personal History

Personal HistoryDeath on the Chilko

September | October 2004 By John W. Collins ’52 -

Interview

Interview“A Change Agent”

September | October 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

Sports

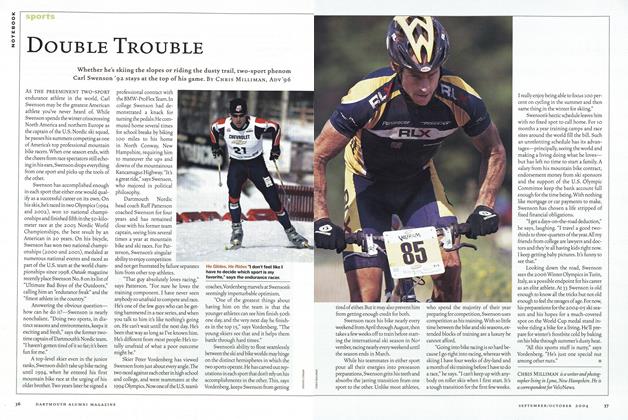

SportsDouble Trouble

September | October 2004 By Chris Milliman, Adv’96

Julie Sloane ’99

-

Article

ArticleLiving on Martian Time

MAY 2000 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Classroom

ClassroomLearning By Doing

May/June 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

Jul/Aug 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNew Dimensions

Nov/Dec 2005 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Cutting Edge

May/June 2011 By JULIE SLOANE ’99

Classroom

-

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWarring Factions

Jan/Feb 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMNot Lost in Translation

Sept/Oct 2009 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMSpeaking to the Future

May/June 2011 By Judith Hertog -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMStar Struck

Mar/Apr 2012 By Judith Hertog -

Classroom

ClassroomLearning By Doing

May/June 2004 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott