Across the Divide

By making a concerted effort to reach out, liberals could get theocrats to buy into mainstream institutions.

July/August 2006 Lucas SwaineBy making a concerted effort to reach out, liberals could get theocrats to buy into mainstream institutions.

July/August 2006 Lucas SwaineBy making a concerted effort to reach out, liberals could get theocrats to buy into mainstream institutions.

SINCE WINNING BATTLES AGAINST communism and fascism, free societies have watched troublesome religious conflicts move to political center stage. Liberal democracies now face a series of tough issues rooted in religious fundamentalism. American society is at odds with itself, marked by fractious debates over religion and politics as liberals fail to give theocrats good reasons to affirm liberal governing institutions.

Theocrats—devout believers who aspire to live according to strict, comprehensive religious ideals—divide naturally into two different kinds: ambitious (such as members of the religious right or the Nation of Islam) and retiring (such as the Amish, members of the former City of Rajneeshpuram in Oregon or polygamous Mormon communities in Utah).

Whether they fervently promote their doctrines or try to withdraw from society theocrats dwelling in liberal democracies present a number of problems for government. For instance, while not all theocrats are prepared to act in illegal or violent ways, many are marked by a preparedness to protect their religion from attack. In cases of perceived interference they have a propensity to strike out violently.

The native-born Islamic bombers who struck targets in London on July 7,2005, are a painfully obvious case in point. America has had its share of violent eruptions from theocrats, too. The quasi-Buddhist theocratic community of Rajneeshpuram is an example. Prior to its collapse in 1985,34 members of this Oregon community were charged with a variety of state and federal crimes including attempted murder, assault, arson, burglary, racketeering and electronic eavesdropping. Another example is the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, who stockpiled weapons and braced for confrontation with government forces in the lead up to the 1993 siege of their community.

Governments severe actions against theocrats, as occurred in Waco, may excite militant responses from extremist groups sympathetic to the theocrats' plight. The federal governments ham-fisted treatment of the Waco affair outraged militant groups in America, spreading disaffection even to those who did not share the Branch Davidians' religious beliefs, catalyzing strikes that included the dreadful Oklahoma City bombing of 1995. Extremist groups continue to view the maltreatment of theocrats as indicative of the moral bankruptcy of a liberal democratic government, lashing out where government is seen to run roughshod over retiring theocratic communities.

In order to make headway on these issues, citizens must consider a particular moral shortcoming that has plagued liberal democracy to this point. One could call it a failure of justification. A well-ordered society should, indeed must, supply explanations for its policies and procedures that are powerful and well reasoned and which go a long way toward justifying the laws and policies its institutions employ, both domestically and abroad. Where laws and policies affect theocrats, the explanations government provides to justify its actions should be based on reasons that theocrats should accept, reasons that hold rationally for theocrats, given their more reasonable concerns and commitments. To date, no such reasons have been given systematically-certainly not at the philosophical level. This failure lays groundwork for future conflicts between theocrats and liberal democratic institutions.

Nor has government done well in providing such reasons in legal settings. Examples date back to the U.S. Supreme Court's odd and unconvincing 1878 judgment disallowing Mormon polygamy a failure of justification that continues to resonate. On that occasion Chief Justice Waite proposed that polygamy "has always been odious" to the civilized nations of Europe, suggesting that the English have for ages treated polygamy as an "offence against society." Partly due to such loose reasoning, I suspect, many theocrats continue to disagree deeply with the values underpinning liberal democratic government, insisting that they have solid, overriding religious reasons for be having in illiberal ways.

Arguments that could justify governmental policies to theocrats—or prompt them to affirm free institutions—need to. derive from the cardinal principle of liberty of conscience, supported by the First Amendment, guaranteed in state constitutions across America and embodied in the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This universal principle that conscience must be free to reject lesser religious doctrines and conceptions of the good—supports limited government with individual protections for religious theocrats to develop a more harmonious relationship with democratic institutions and citizens. A more judicious appreciation of liberty of conscience can help to defuse potential flare-ups between theocrats and government. freedom, among them the right of persons to exit their communities of faith in cases where they feel compelled to depart. And it gives cause to value free speech for culturally and religiously plural societies in which vulnerable religious minorities are often ensconced. Liberty of conscience is a political issue in the end, and religious practitioners require political institutions that will protect their practices and not harm them unnecessarily. The value of liberty of conscience can inform and justify governments treatment of theocrats and could prompt

What's more, society can mitigate the tendency of theocratic communities to turn to violence by lessening those groups' sense of persecution. As a first step, citizens should resist temptations to throw around unwarranted suggestions that members of theocratic communities are backward, abusive to women and children or simply crazy. It matters how religious groups get labeled: Religious groups tend to oppose legal and political impositions peacefully unless members perceive a threat to their group's institutional structure or to their very religion. Byway of examples, the Branch Davidians and the Rajneeshees each became fixated on their own persecution, resultant from perceived attacks on their religious communities. The same has held true for religious groups outside of America that turned to violence, such as Aum Shinrikyo in Japan.

Citizens concerned with the influence of ambitious theocrats in domestic politics would do well to insert themseves into theocrats' social networks and engage believers directly. This has the potential tential notonly to increase understanding between more liberal-minded citizens and their theocratic counterparts, but also to modify theocrats' attitudes and their behavior in turn. Ambitious theocrats are available for such engagement in local neighborhoods, clubs, churches, places of employment and extended families. While ambitious theocrats might seem to present a united front, such is not the reality. Their theological and political convictions are split, both with respect to others who hold their doctrine as well as across ambitious theocratic groups more widely. There is no unanimity among Catholics on the topic of abortion, for example, and the most intransigent opponents of abortion are evangelical Protestants.

These strategies to improve understanding could be joined with a larger international approach aiming to normalize and improve relations with theocratic groups, movements and polities around the world. Greater engagement would help there too, as would principled and conscientious dealing with religious practitioners who question the value free institutions might hold for them. The promise of such efforts could be a new dawn for free societies; the failure to engage will mean not just persistent disappointment but possible political disaster.

Society can mitigate the tendency of theocratic communities to turn to violence by lessening the groups' sense of persecution.

LUCAS SWAINE is assistant professor ofgovernment and the author of The Liberal Conscience: Politics and Principle in a World of Religious Pluralism (ColumbiaUniversity Press, 2006).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July | August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

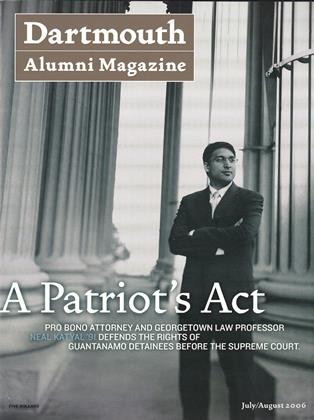

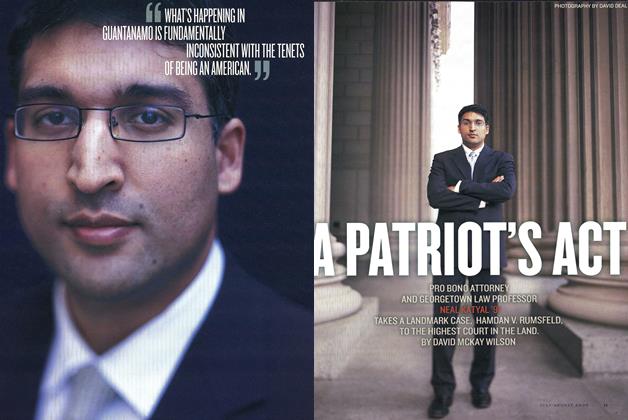

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Patriot’s Act

July | August 2006 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureMeet the Greeks

July | August 2006 By ALLISON CAFFREY ’06 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July | August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July | August 2006 By Rodger Ewy '53, Rodger Ewy '53 -

CAMPUS

CAMPUSMaking a Comeback

July | August 2006 By Lauren Zeranski ’02

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMillennial Mindset

May/June 2007 By Aine Donovan -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Next Frontier

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jay C. Buckey Jr. -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July/August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThey’re Off The Mark

Nov/Dec 2000 By Matthew Slaughter -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONDesigner Genes

Mar/Apr 2008 By Ronald M. Green -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONMyths of Innovation

Mar/Apr 2006 By Vijay Govindarajan and Chris Trimble