Millennial Mindset

Dartmouth’s Ethics Institute director assesses the latest “greatest” generation, today’s college kids.

May/June 2007 Aine DonovanDartmouth’s Ethics Institute director assesses the latest “greatest” generation, today’s college kids.

May/June 2007 Aine DonovanDartmouth's Ethics Institute director assesses the latest "greatest" generation, today's college kids.

"BACK WHEN I WAS AT DARTMOUTH THINGS WERE DIFFERENT," LAMENT many former Dartmouth students when they read The D or visit campus and witness an event that strikes them as distinctly out of character for their beloved College on the Hill. How different are the values of students in 2007 from previous years? Is the world on a fast track to destruction and moral nihilism with this generation poised to take charge?

Recent events on campus have, once again, sparked a debate overvalues and cultural norms. An important consideration in this debate, however, is the distinction between developmental stages that all people at all times undergo and the socially imposed trends that young adults can fall prey to. Moral psychology offers helpful insight on this point. Two types of change occur during the college years: developmental, which happens as a natural part of identity formation, and environmental, which happens due to external variables that exert an influence on the student. Developmental changes are predictable and sequential, oftentimes frustrating for parents and teachers because young adults are in the process of exerting independence and trying on a variety of political and personal masks that will eventually form their identities. Environmental changes are not predictable and often have serious consequences for healthy development. September 11 was such an event; it altered the lives of all Americans but perhaps especially those teenagers who stood poised to enter adulthood in 2001 and witnessed a total collapse of the order they counted on for a smooth transition into the adult world.

Studies on generational values indicate that current college students exhibit a complex set of competing values. The millennial generation, born between 1982 and the present, has been shaped by technological advances in communication (the Internet) as well as social changes (family redefined), global changes (terrorism) and scientific changes (the environment, biotechnology). They are the first generation to be conceived through in-vitro fertilization or specialty sperm banks and are often an only child to parents who lavish love and extremely high expectations upon their "special child." What has the result been for the millennial generation? Perhaps surprisingly, this generation—as a group—does not fall victim to past generations' sins of excess, sloth or self-indulgence. Instead we find that today's college students are highly motivated to "do good in the world," whether through working for a socially responsible company or serving the community through volunteerism.

Unfortunately, as a group they also self-report much higher levels of cheating than previous generations. As a generation that has been pushed and prodded toward excellence by a competitive community of family, teachers and coaches, the lapse into unethical behavior is nearly inevitable. Studies from the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA indicate that while college students are more optimistic and service-oriented, they are also studying less, cheating more and less involved in social activism about issues that will deeply affect their lives in the future. Despite ethical lapses when it comes to cheating in order to fulfill expectations, the moral foundation of the millennial generation is a solid one: They are thoughtful and care deeply about the future of the planet and those who inhabit it.

What, then, can a college experience do in helping to shape young men and women who will resist the temptation to cut corners? The college years can, and should, contribute to the overall development of the young adult: the mind, the body and the spirit. Dartmouth has long held this educational objective as a primary goal. The most obvious element is the curriculum, but beyond the classroom students engage in community service, athletics and extracurricular experiences that shape character and establish patterns of behavior that underlie moral citizenship. That students are typically involved in organized activities outside the classroom distinguishes Dartmouth's campus life.

A sad example of the millennial rush toward perfection can be found in the Harvard sophomore found guilty of plagiarism last year. After an over-achieving upbringing in suburban New Jersey, Kaavya Viswanathans parents hired an elite college application service for their daughter. As her push toward Harvard intensified, the counselor suggested an emphasis on the high school students budding interest in fiction writing. Rough drafts of a high school fiction project were "edited" by a book packager and the resulting book, How Opal Mehta Got Kissed,Got Wild, and Got a Life, was snapped up by Random House and optioned as a film. Those achievements alone would be monumental for most 17-year-olds, but for Viswanathan it was a ticket into the millennial brass ring club: Harvard. Less than a year after publication it was discovered that significant portions of the book were lifted from another fictional account of millennial angst. The ethical questions abound: Was it the fault of pushy parents? Over-zealous college preparation businesses? Or a society engaged in Ivy-League mania? Whatever the motivations for an extremely talented young woman to engage in behavior that will undoubtedly haunt her for a lifetime, the need for change is apparent. Our over-achieving 20-somethings have the makings of another "greatest generation" but they will not realize that ambition if it is buried under the cloak of self-absorption.

AINE DON OVAN is executive director of theDartmouth Ethics Institute and teaches business ethics at the Tuck School.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

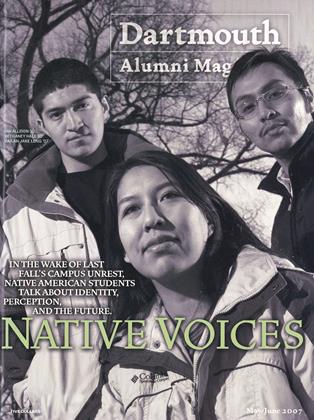

Cover StoryNative Voices

May | June 2007 By CATHERINE FAUROT, MALS’05 -

Feature

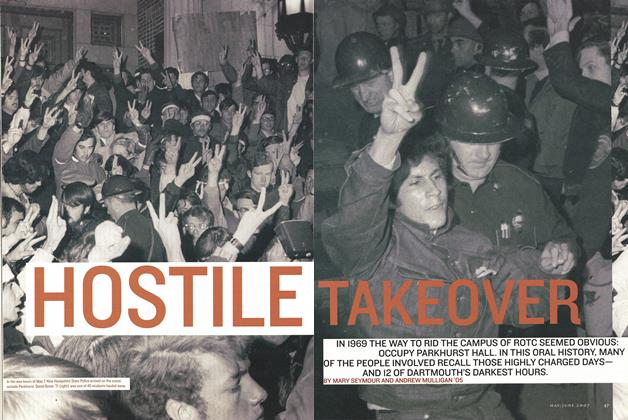

FeatureHostile Takeover

May | June 2007 By MARY SEYMOUR AND ANDREW MULLIGAN ’05 -

Feature

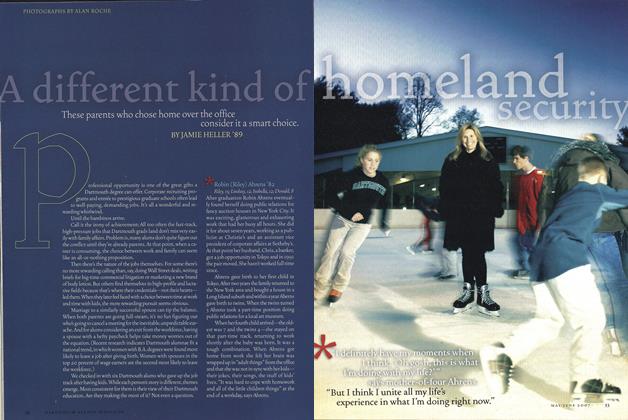

FeatureA Different Kind of Homeland Security

May | June 2007 By JAMIE HELLER ’89 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2007 By Joe Novak '52 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThe Pursuit of Happiness

May | June 2007 By Daniel Becker ’84

FACULTY OPINION

-

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONTrain The Brain

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By CECILIA GAPOSCHKIN -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

Mar/Apr 2004 By David C. Kang -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Next Frontier

Jan/Feb 2001 By Jay C. Buckey Jr. -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionWater Under Fire

July/August 2001 By Joshua Hamilton -

FACULTY OPINION

FACULTY OPINIONHappiness and the Classics

Jan/Feb 2011 By Paul Christesen ’88 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionCan You Believe It?

May/June 2004 By Walter Sinnott-Armstrong