Soviet Union

Russian professor Lev Loseff keeps alive the works—and spirit—of his exiled countryman, friend and fellow poet, Joseph Brodsky.

Sept/Oct 2005 ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75Russian professor Lev Loseff keeps alive the works—and spirit—of his exiled countryman, friend and fellow poet, Joseph Brodsky.

Sept/Oct 2005 ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75RUSSIAN PROFESSOR LEV LOSEFF KEEPS ALIVE THE WORKS—AND SPIRIT—OF HIS EXILED COUNTRYMAN, FRIEND AND FELLOW POET, JOSEPH BRODSKY.

In the early 1970s Lev Loseff, a husband and father of two, a Russian writer and editor of children's books. Possessed a loyalty to friends whose ways of thinking and behaving were at odds with the government's—and a willingness to act on his impulses. He was a man with a troubled conscience. In Leningrad this was a problematic—volatile—resume of character traits, and enough to put Loseff squarely in harms way.

Losff's personality had revealed itself subtly, and principally to only himself and his family. Born in 1937 into a well-off family (his lather was a noted writer of childdren's literature), Loseff received a fine education and, at the University of Leningrad, steered himself toward a career in journalism-something he considered to have a degree of intellectual helft. But once he had finished his compulsory service in the Soviet armed forces and begun the actual practice of reporting on affairs in the U.S.S.R., he quickly realized that to be a "journalist" in a totalitarian reginme was to serve the state. This was untenable to the bright youngman. "What I wanted was to write and, as far as possible, not to assist evil," says Loseff.

So he looked around for another way to put his acumen and considerable gifts to work. He found safe harbor in the family profession. "I followed my father, and joined a magazine tor children," says Loseff. He would remain at chat magazine, Kostyor, for 13 years, until circumstances forced an end to that career—and to his lite as a Soviet citizen. As Loseff was rising in the 1960s to the editorship of Kostyor, gaining not only respect but also a modicum of wealth ("I had the biggest apartment among my friends, and I owned it," he says), his career intesected with that of another young Russian belle lettrest, Joseph Brodsky. Brodsky, says Loseff, "had dropped out of school when he was 15 but was an extremely educated man. Dostoyevsky, multilingual. He was brilliant. I could see this right away.

"We were both part of this wide circle of friends in the 1960s, and at Kostyor I had an opportunity to commission some poems," Loseff continues, speaking in accented English in his Reed Hall office. "I asked some young poets I knew to submit. Brodsky was so skillful, such a great master at everything he did, and when his poem came in it was very good. That was at the end of 1962, and I was the first to publish a Brodsky poem. It was 'The Ballad of a Little Tug Boat'—a romantic poem about a tug that did the hard work in a Leningrad port while all the big boats go around the world. It was not a political poem, not at all, but very good."

When it is suggested that "The Little Tug Boat" reflects Brodsky's later, more mature work—he was ever a romantic, ever dealing in human emotion and desire, life and death, and never, despite his personal history, a political poet—Loseff says: "Its a good point. I never thought of that, but it was quite characteristic." Less characteristic but equally charming were other Brodsky submissions (all accepted) to Kostyor: translations of rhymes by Muhammad Ali and of the Beatles' "Yellow Submarine."

As Brodsky's reputation as the greatest Russian poet of his generation grew, so did his difficulties with the Soviet regime. He was famously put on trial and, in 1972, after serving 18 months of a five-year sentence in a labor camp, he was exiled from the country. A terrible blow," says Loseff.

In America Brodsky gained worldwide fame and acclaim before his death of a heart attack in 1996 at age 55. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1987, was named his adopted land's poet laureate in 1991 and worked to bring poetry to the masses—to make it, he said, "as übiquitous as the nature that surrounds us, and from which poetry derives many of its similes; or as übiquitous as gas stations, if not as cars themselves." Brodsky also made a memorable commencement speech at Dartmouth for the graduating class of 1989. "He warned the graduates that a great part of their future lives would be possessed by boredom and monotonous routine," says Loseff. "It was wonderfully poetic. Half the audience was captivated and touched, while the other half was listening with their jaws dropped."

Before he left for America, Brodsky had never taken care of his archive, according to Loseff. Several of us started collecting his unpublished poems, and much of that now forms the basis for all of his collections," says Loseff. "He kept us busy, and the work was in some ways dangerous. My own situation became rather precarious. I had all the reasons to believe I was under surveillance. I applied for an exit visa in 1975, knowing my chances were 50-50 that I would be denied as a refusenik." He and his family were allowed to leave the U.S.S.R., and Loseff has been back precisely once, eight years ago, to deal with the death of his last remaining relative there.

Beginning in 1979 Loseff built an enormous reputation among students and colleagues as a professor in Dartmouth's Russian language and literature department. "What I am trying to do in class is simply sharing with students my thoughts about the books and soliciting their responses," he says. "Sometimes that is exhilarating, sometimes frustrating. The class I enjoy teaching the most is freshman seminar. First-year students are so enthusiastic about learning and don't think that it is uncool to talk about big questions such as the meaning of life or the existence of God."

Loseff also developed as a poet. While only a few of his poems have been published in English, it's possible more may be translated and published in Britain in the near future. As for his art, Loseff is attractively self-effacing: "It's hard to qualify your poetry. It's like talking about your own physical appearance. If it is about Russia, it's that it has always been therapeutic writing—and poetry being poetry, it's always an expression of the subconscious. If I was ever proud of my own poetry, it was when it was pointed out that it has nothing to do with Brodsky's. Whenever I find a line or a single word that is reminiscent of Brodsky, I change it."

Which is not to say that Loseff has distanced himself from his friend and countryman in all ways—not at all. He has continued to work on Brodsky's poetry since the poet's death. Five years ago Loseff was awarded a $35,000 Guggenheim Fellowship—one of 182 granted to nearly 3,000 applicants in 2000—to support the completion of his massive edition of Brodsky's complete works. That effort continues. "Sometimes such projects outgrow their original designs. This one is annotated, bilingual and with a critical biographical essay—and it's grown much bigger than expected," Loseff says. "Brodsky said he didn't want anyone to write his biography, so it's a little tricky. What I'm trying to do is not a gossipy biography. That's what Brodsky didn't want. It's a biographic look at his development as a poet, his upbringing in Stalin's time, the cultural influences, how he had just barely begun high school and dropped out, how he went on from that."

Asked if there is a dramatic episode in the essay recounting the precise moment when his own fascinating life intersected so fatefully with Brodsky's, Loseff answers: "That's interesting. No. Brodsky and I tried on many occasions to remember how we met that first time, and we never could. One day, suddenly, we were friends.

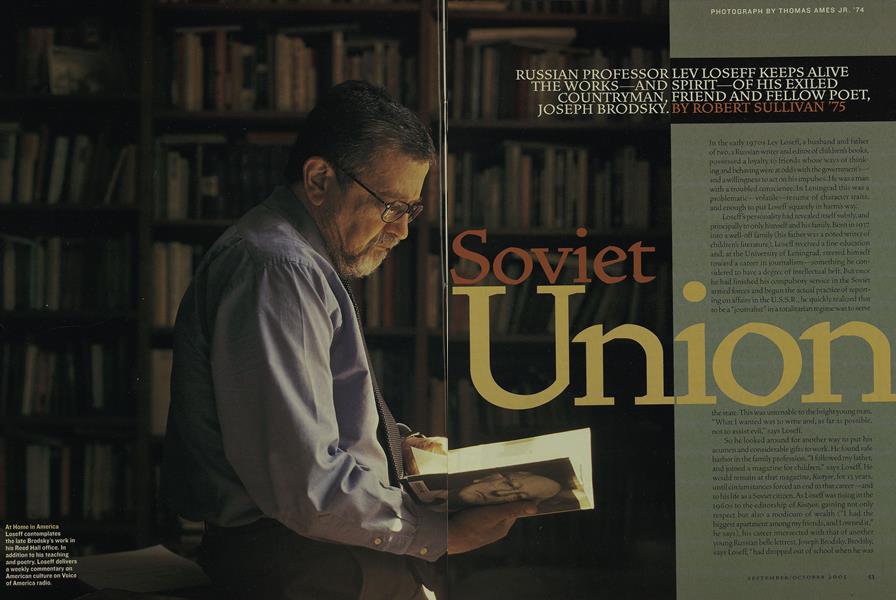

At Home in America Loseff contemplates the late Brodsky's work in his Reed Hall office. In addition to his teaching and poetry, Loseff delivers a weekly commentary on American culture on Voice of America radio.

"I had reason to believe I was under surveillance," says Loseff. "I applied for an exit visa in 1975, knowing chances were 50-50 that I would be denied as a refusenik."

ROBERT SULLIVAN, deputy managing editor of LIFE and editorialdirector of LIFE Books, is the author of Our Red Sox: A Story of Family, Friends, and Fenway (Emmis Books).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

September | October 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

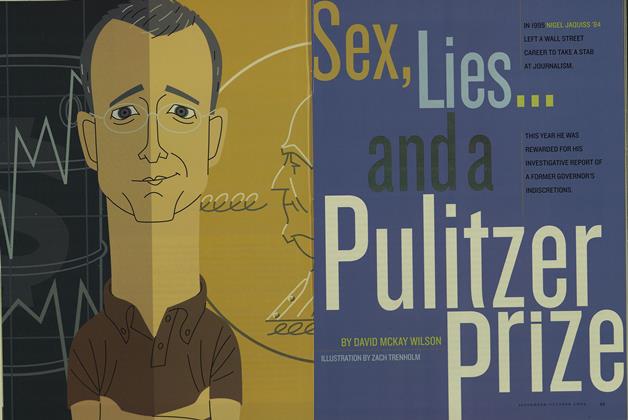

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

September | October 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBand of Sisters

September | October 2005 By Maura Kelly ’96 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTENo Quieter Bed

September | October 2005 By James Zug ’91 -

Interview

InterviewThe Archivist

September | October 2005 By Sue DuBois ’05 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

September | October 2005 By BONNIE BARBER

ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

December 1990 -

Feature

FeatureMoriarty Ad Lib

Winter 1993 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July/August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

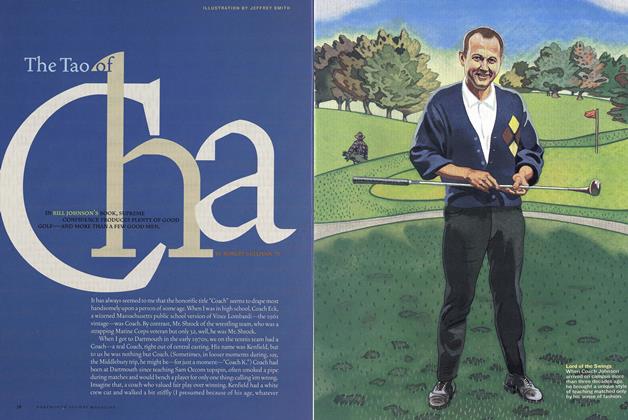

Sports

SportsThe Tao of Cha

May/June 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Unknown and Unsung Undergraduate Days of Stephen Colbert ’86

July/August 2008 By Robert Sullivan ’75 -

RETROSPECTIVE

RETROSPECTIVEHe Wept Alone

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

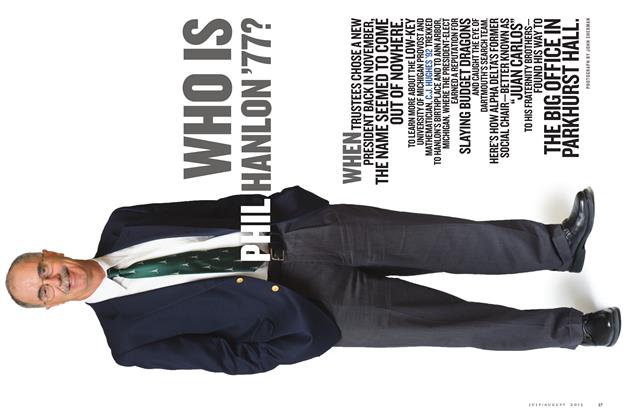

FeatureWho Is Phil Hanlon ’77?

July/Aug 2013 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureInvocation

JULY 1971 By CHARLES F. DEY '52 -

Feature

FeaturePoet of Place

December 1973 By R.B.G. -

Feature

FeatureThe Outward Bound Term

DECEMBER 1970 By Robert B. Graham Jr. '40 -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08